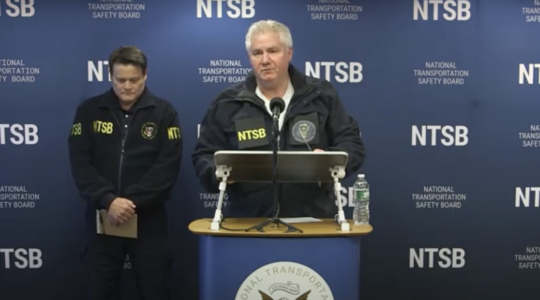

Michael Oren, left, Israel’s ambassador to the United States, greets U.S. Secretary of Defense Charles Hagel, right, with Israeli defense official Udi Shani upon Hagel’s arrival at Ben Gurion Airport in Israel, April 21, 2013. (U.S. Embassy Tel Aviv)

WASHINGTON (JTA) — Michael Oren was deep inside the State Department, relaxed and taking on all comers: He had the facts on his side.

It was 2004 and the department was reviewing newly declassified National Security Agency evidence reinforcing Israel’s longstanding claim that its 1967 air attack on the USS Liberty spy ship was a mistake. The attack killed 34 American personnel.

Oren, a preeminent historian of the Six-Day War, was not suffering gladly those at the State Department conference who continued to insist, despite all evidence to the contrary, that Israel intended to murder the Americans. Both sides, Oren said, were guilty of negligence.

Israel’s accusers sputtered and then erupted into shouts. Oren sat back in his chair, surveyed the room and smiled.

It may have been the last time Oren was completely at ease in the halls of the State Department.

Oren became Israel’s ambassador to Washington in 2009 and has since been in the hot seat at the State Department multiple times, summoned to provide “clarifications” following some controversial Israeli action. It’s a function he has been called upon regularly to perform during his tenure, which he announced last week would wrap up by the fall.

“I am grateful for the opportunity to represent the State of Israel and its government, under the leadership of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, to the United States, President Barack Obama, the Congress, and the American people,” Oren said in a July 5 statement. “Israel and the United States have always enjoyed a special relationship and, throughout these years of challenge, I was privileged to take part in forging even firmer bonds.”

His successor will be Ron Dermer, a top aide to Netanyahu who like Oren is U.S.-born.

Oren’s Washington stint has come during a period fraught with tension between two men he says he admires — Obama and Netanyahu — as well as between the Israeli government and the American Jewish community.

The envoy was at the forefront of efforts to push back against rumors — some of them reportedly planted by Netanyahu’s Jerusalem office — that Obama had snubbed Netanyahu on a number of occasions.

Notably in March 2010, rumors swirled that Obama had snubbed Netanyahu during a visit to the White House. That was just weeks after a near-disastrous trip to Israel by Vice President Joe Biden, on the eve of which Israel infuriated the administration by announcing new building in eastern Jerusalem.

In refuting the snubbing charge, Oren got into the gritty detail of whether Netanyahu had entered through the front or the back (it was the front) and whether Obama’s wife and daughters had snubbed Netanyahu during dinner (they were in New York at a show.)

The rockiest point may have come last year during a presidential campaign in which Netanyahu was widely seen as backing Obama’s opponent, Mitt Romney. Top Democrats were furious with Netanyahu for criticizing Obama’s Iran policy in September, just two months before the election.

Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-Fla.), the chairwoman of the Democratic National Committee, cited Oren in hitting back at Republicans for making Israel a partisan issue.

“I’ve heard no less than Ambassador Michael Oren say this, that what the Republicans are doing is dangerous for Israel,” Schulz said at her party’s convention in Charlotte, N.C., in September.

Oren quickly released a statement clarifying that he had never singled out any party as guilty of making Israel a partisan issue.

“I categorically deny that I ever characterized Republican policies as harmful to Israel,” Oren said.

When Oren was able to control the agenda, he had three preferred topics: the proto-Zionism that threaded throughout American history, manifest in the writings and sayings of figures such as Abraham Lincoln and Woodrow Wilson; the deep intensification of security cooperation between Israel and the United States during the Obama-Netanyahu era, a fact often lost in the verbal volleying on the peace process and Iran; and the touting of Israel’s cultural and scientific achievements.

“For a foreign ambassador, to be able to lecture Americans about Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln and Harry Truman was incredibly unique and instructive in helping to represent the position of the State of Israel,” said William Daroff, the Washington director of the Jewish Federations of North America.

Oren, working behind the scenes, also was able to advance one of his own top priorities: addressing the alienation with some Israeli practices among Jewish Americans. He was a leading voice in making clear to Israeli government leaders that the perception of an erosion of women’s rights in Israel was infuriating the Jewish leadership in the United States. This year he helped broker a tentative deal that would expand access for women at the Western Wall.

He also advocated for ties with J Street, the liberal group pushing for more robust American involvement in advancing the peace process. The ties are limited, but nonetheless notable, considering the fierce resistance to any engagement with the group in Netanyahu’s camp.

Oren gamely took the case for liberal Israel into whatever precinct would have him. He delivered a speech a year ago in Philadelphia’s Equality Forum, noting advances in gay rights in Israel in recent decades.

Oren’s office declined an interview, saying he preferred to review his career here closer to his departure date, which has yet to be specified. But the New Jersey-born Oren, 58, in a 2009 interview at the outset of his ambassadorship, told JTA that transitioning from the truth telling of scholarship to the spin of diplomacy was like going from “free verse to writing rhymed haiku.”

In March, however, Oren was able to synthesize the two when he joined his U.S. counterpart in Tel Aviv, Dan Shapiro, in designing Obama’s first visit to Israel as president.

The standard stops — Yad Vashem, the Prime Minister’s Office — would not suffice, Oren and Shapiro decided. This is where Oren the historian fused with Oren the diplomat. The Israeli ambassador proposed a visit to the Dead Sea Scrolls that would emphasize what many had felt was lacking from Obama’s 2009 speech to the Arab world: recognition of Israel’s ancient ties to the land.

The trip was a success. Obama’s culminating address to a Jerusalem hall packed with university students, laced with references to the land’s Jewish heritage as well as appeals for a more accelerated peace process, earned long and thunderous applause.

Off in a corner, Oren and Shapiro fell into a long hug.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.