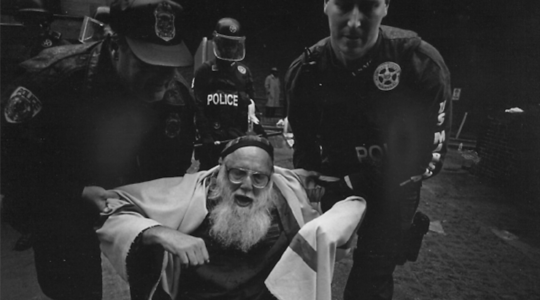

Frank Lautenberg, before he became a U.S. senator, with then-Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir. (Bonnie Lautenberg’s personal collection)

WASHINGTON (JTA) — In 1982, Frank Lautenberg was running for New Jersey’s U.S. Senate spot at a time when Democrats in the state were down on their political fortunes.

The Jewish community knew and liked Lautenberg, a data processing magnate who died Monday at 89 after serving more than 30 years in Washington. Lautenberg had been chairman of the United Jewish Appeal in the previous decade and turned the charity around during a parlous economy.

But Jacob Toporek, who managed Lautenberg’s Jewish campaign that year, recalls that New Jersey Jews were skeptical of Lautenberg’s chances: How likely was this political neophyte to win when the Republicans were on the rise both in the state and nationally?

“We ran an ad in Jewish papers with a picture of him with Golda Meir, with a simple caption: ‘Commitment then, commitment now,’ ” said Toporek, who now directs the New Jersey State Association of Jewish Federations.

The pitch worked, and the Jewish vote helped vault Lautenberg to 30 years in the Senate, where he made good on the implicit promise in the ad, becoming a history-making champion of Soviet Jewry.

“When he became involved in electoral Jewish politics, he didn’t forget his Jewish involvement,” said Mark Levin, the director of NCSJ, formerly the National Council of Soviet Jewry. “He became one of the leading advocates for Jews in the Soviet Union.

Lautenberg died Monday morning of viral pneumonia, his office said in a statement that outlined an array of far-reaching legislation in which he had a hand. It included laws that kept convicted domestic abusers from owning guns, banned smoking on planes and made 21 the minimum drinking age.

Those who were closest to Lautenberg said the law that had the most meaning for him was the one that bears his name.

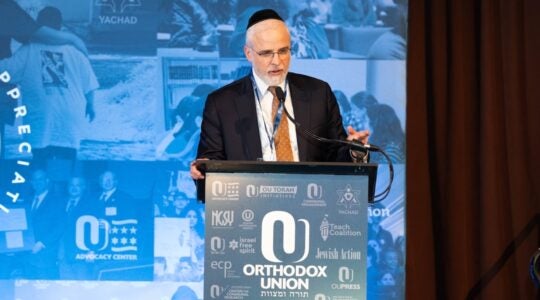

Sen. Frank Lautenberg attending a Holocaust memorial ceremony in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, May 1, 2008. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty)

The Lautenberg Amendment, passed in October 1989, facilitated the emigration of Soviet Jews by relaxing the stringent standards for refugee status, granting immigrant status to those who could show religious persecution in their native lands.

At a tribute in New York to Lautenberg last week hosted by Hillel: The Foundation for Jewish Campus Life, Lautenberg’s wife, Bonnie, called the amendment his “proudest achievement.” Bonnie Lautenberg accepted the award in his stead because the senator was too ill to attend.

The law “fundamentally changed the face of the American Jewish community,” Levin said, noting that it resulted in the emigration of hundreds of thousands of former Soviet Jews to these shores.

Mark Hetfield, the president of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, the leading Jewish immigrant advocacy group, said Lautenberg’s final legacy may be making his amendment permanent.

The amendment now requires renewal every year, and at times has been threatened when Congress cannot agree on a budget, as was the case this year.

An amendment authored by Lautenberg to the immigration overhaul now under consideration in Congress would allow the president to fund the Lautenberg provisions without congressional approval. The amendment was part of a package approved last month by the Judiciary Committee, and the odds are that the full bill will pass.

“The law has been a lifesaver for hundreds of thousands of people who have fled religious persecution,” Hetfield said.

Lautenberg grew up in Paterson, N.J., the son of poor Jewish immigrants from Poland and Russia. He liked to say his parents “could not pass on valuables, but left me a legacy of values,” according to a release from his office.

He served in the U.S. Army Signal Corps in World War II and then earned a degree in economics at Columbia University through the G.I. Bill. The role of government in giving a poor kid from Paterson a shot at an Ivy League education undergirded Lautenberg’s subsequent commitment to social justice.

He started Automatic Data Processing and built it into the largest data processing firm in the world by 1974, when he became chairman of the United Jewish Appeal. Within a year Lautenberg had increased its charitable intake to the second-highest level in its history — an extraordinary accomplishment at a time when the United States was reeling from the energy crisis.

His business success meant he could pay for much of his Senate run in 1982, when the seat was open because the incumbent Democrat, Harrison Williams, resigned after being implicated in a bribe-taking scandal.

Lautenberg’s opponent, moderate Republican congresswoman Millicent Fenwick, had the backing of the state’s popular GOP governor, Thomas Kean, and was favored to win. But Lautenberg prevailed, 52 percent to 48 percent.

His Senate career was marked both by unflinching liberalism and his reputation for integrity. Lautenberg retired in 2001, but in a replay of his 1982 election, the state party called on him to run in 2002 after the scandal-plagued Robert Torricelli was forced to resign. This time, Lautenberg won handily.

His liberalism was rooted in his hardscrabble youth overshadowed by the death of his father from cancer when he was a boy, according to lifelong friend and fellow Paterson native Stephen Greenberg, now chairman of NCSJ.

“Paterson was the silk center of the world at the time,” Greenberg said. “You had this massive number of Jews from Russia and Poland in that whole area. His father worked in the silk mills, and Frank believed that was the predominant source of his cancer.”

Lautenberg became the Senate’s leading advocate of public safety, writing laws that improved standards for clean coastal waters and tripled liability for oil spills. In 1968 he founded the Lautenberg Center for Immunology and Cancer Research at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

He launched crusades for safer conduct on the roads, rails and in the air. During his short absence from the Senate in 2001-02, the Secaucus Junction train station was named for him, honoring his work on expanding rail transportation in the eastern United States.

The last World War II veteran in Congress, Lautenberg also led passage of the “G.I. Bill for the 21st Century,” extending education benefits to veterans of the post-Sept. 11 wars.

He also was a lead champion of women’s rights, advancing laws mandating sex education and keeping pharmacists from invoking religious beliefs in order to deny service to women seeking birth control medications.

At the time of his death, Lautenberg was pushing hard on a number of reproductive issues, including the repeal of a law banning funding for groups overseas that provide abortions and extending abortion rights to women serving in the military overseas.

“It’s a loss,” said Linda Slucker, the president of the National Council of Jewish Women. “We always needed that voice, and he brought that voice to the Senate.”

Lautenberg was in Israel on Sept. 11 2001, on a federation mission that included a stop at a park in Rishon Lezion named for him. Upon learning of the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, he used his pull as a former senator to secure spots on flights back to the United States, so the Jewish officials on the trip could attend to families affected by the attack.

“Because of him, we were able to make international flights back to the United States,” recalled Max Kleinman, the executive vice president of the Jewish Federation of Greater MetroWest in New Jersey.

In 2011, Lautenberg initiated a non-binding Senate resolution that recommended marking Sept. 11 with a moment of silence; it passed unanimously.

Lautenberg gave prodigiously to Israel and was its champion in the Senate. But he also was outspoken in criticizing the state when he thought it erred, said Rabbi David Saperstein, the director of the Reform movement’s Religious Action Center.

“He was a champion for us on religious pluralism and the right to marry in Israel,” Saperstein said. One of Lautenberg’s children had married a non-Jew, and that Israel would question the Jewish status of any of his grandchildren “infuriated” him, the rabbi added.

Despite his firebrand reputation, Lautenberg was avuncular in person. Jewish staffers on Capitol Hill called him “zayde,” Yiddish for “grandfather,” recalled Rabbi Levi Shemtov, director of American Friends of Lubavitch. Lautenberg was a regular at holiday events, and if he noted Jewish officials in the halls, he would stop and chat.

“He felt connected,” Shemtov said.

The NCJW’s Slucker, who was friends with Lautenberg through their synagogue, Temple Sharey Tefilo-Israel in South Orange, N.J., said he could not walk through the sanctuary’s aisles on the High Holidays without meeting and greeting fellow congregants.

“He was a real listener,” she said.

Lautenberg’s faith and Americanism were wrapped one into the other, the NCSJ’s Greenberg recalled. Lautenberg was outraged in 1985 to learn that President Ronald Reagan was planning to mark the 40th anniversary of V.E. Day with a visit to Bitburg, a German military cemetery that included the remains of officers of the murderous SS, the Nazis’ elite military unit.

Jewish leaders were outspoken in their fury, but Lautenberg decided his protest would be personal. On May 4 1985 — the day before the anniversary — Lautenberg toured Dachau with Greenberg and Morris Glass, a survivor of the camp. From there they went to Munich to pay tribute to the 11 Israeli athletes murdered by Palestinian terrorists at the 1972 Olympics.

On May 5, the day Reagan was at Bitburg, the trio was at the massive U.S. military cemetery at Henri Chapelle in Belgium, where Lautenberg laid wreaths on the gravestones of three New Jersey soldiers — one Jewish and two Christians.

“We were two Jewish boys from Paterson, N.J., doing their part when the president was going to the wrong place to honor the wrong people,” Greenberg said.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.