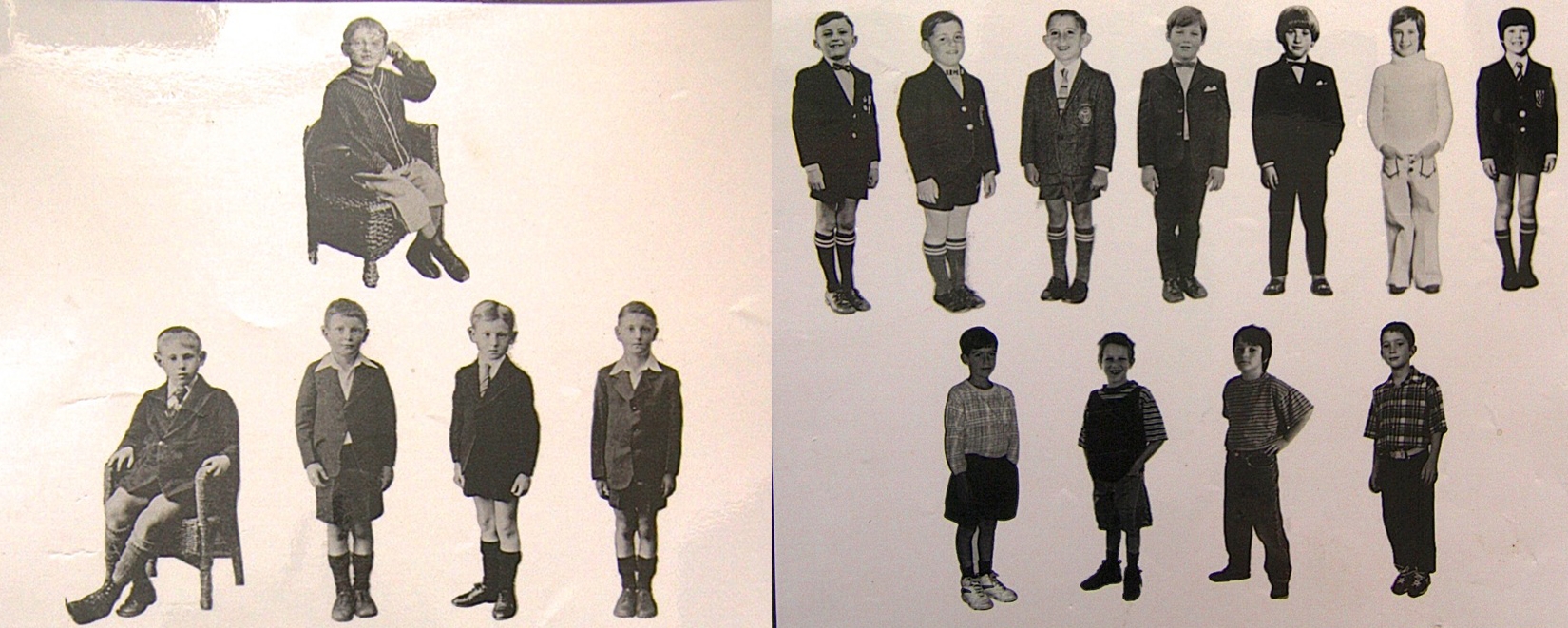

Multiple generations of Lieberman boys are displayed on a family collage that members of the family have been displaying for several generations. (Courtesy Eric Lieberman)

The Seeking Kin column aims to help reunite long-lost relatives and friends.

BALTIMORE (JTA) – Four generations of Lieberman boys stare out from a collage that hangs from a corridor wall in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Each boy is 7 — a significant number in the life of the first boy, from whom the others descend photographically and genealogically.

An ordeal that befell Israel Lieberman at that age would spur him to safeguard his sons against disaster, and they have done the same for their sons.

The collage attests to Lieberman’s scars, but also to his mother’s unquenchable devotion.

Lieberman, known as Izzy, knew how to make money as an adult. He bought properties that became the real estate company his descendants still operate. Izzy also owned shops selling timber, hardware and bicycles.

His survival instincts and street smarts were developed almost immediately upon reaching South Africa in 1899. Izzy Lieberman and his father, Avrom Yossel Lieberman, had departed their native Vilnius, Lithuania; Rachel Lieberman and the couple’s four other children remained behind until Avrom Yossel could send for them.

Minutes after stepping off the boat in Cape Town, Avrom Yossel told his son to wait with the suitcases, then set off to purchase some food. This was at the dawn of the Anglo-Boer War, and Avrom Yossel sported short hair and a long red beard. He had no idea his appearance pegged him for a Boer, or farmer, presumed to be among those rebelling against British rule.

Avrom Yossel would get only a few blocks before he was seized by colonial authorities, his pleas for understanding about his waiting son ignored.

Released from jail more than a week later, Avrom Yossel returned to the spot where he had left Izzy — Izzy was gone.

The boy didn’t know what to do. At first he hid in an enormous, empty oil drum to get out of the rain. It soon became his home.

Izzy met other children living on the street, and they befriended him. They were of a class known as “Cape Coloureds,” of mixed-race ancestry and later subject to apartheid-era separation laws. To get by, Izzy learned how to pick pockets and steal food. The street children all but adopted Izzy and brought him to their school, where he was the only white pupil.

Avrom Yossel was devastated, of course. He wrote home telling Rachel that Izzy was dead, but nothing about the circumstances. After all, he figured, a child couldn’t survive on the city’s streets. Avrom Yossel eventually despaired of searching and moved to Johannesburg, where he bought and sold second-hand clothing.

Years went by and the teenage Izzy joined his chums heading to the Northern Cape Province, where diamonds were being mined. Meanwhile, Rachel and the remaining children endured their own travails to reach South Africa. More than a decade after Avrom Yossel and Izzy had left, the others boarded a boat to Cape Town. Rachel trod down the gangplank and immediately ordered Avrom Yossel to take her to Izzy’s grave.

Her husband confessed that Izzy had been lost, so he’d presumed him dead. If there was a grave, he didn’t know its location.

Rachel refused to believe that Izzy was dead. She retrieved the only photograph she had of him – Izzy at age 7, taken just before he and Avrom Yossel departed Vilnius – and placed notices in multiple newspapers. A teacher at Izzy’s school recognized his name and photograph. She bumped into Izzy in Cape Town and whipped out the paper she had kept. The teacher told him about his parents’ search.

“That can’t be,” he replied. “They threw me away.”

Nevertheless, Izzy ventured to Johannesburg, to the address given in the notice. He peered through a window at the residence. Arriving home from work, his brothers noticed the strange figure and attacked him. That was understandable; many imposters had claimed to be the long-lost Izzy. On this night, Izzy’s parents ran to the source of the commotion.

Rachel recognized the bleeding, dazed figure and proclaimed, “That’s Izzy!” Avrom Yossel said, “No, it can’t be.”

It was. Father and son were “psychologically damaged” from what had happened and became estranged, said Eric Lieberman, Izzy’s grandson and a real estate agent in Los Angeles. At the Jewish cemetery in Brixon, near Johannesburg, Avrom Yossel’s grave lay unmarked because of Izzy’s edict against honoring the man who had abandoned him. Just six or seven years ago, some of Avrom Yossel’s great-grandchildren finally placed a proper marker. The family posed next to it for a photograph.

Pictures are the family’s legacy. Izzy had portraits made of his sons as each turned 7 – a precaution against anyone being cut off from the family for 11 years, or at all, as he was. First there was Leon and then Robert, Eric’s father. After Robert, Sam and Julius.

The pictures eventually were made into a collage, and they created ready-made “wanted” posters. Images of the next generation’s boys became part of the collage, too, in birth order and always in black and white: Eric, Eric’s brother Alan, Jeffrey, David, Warren, Dan and Guy. So, too, for the next generation: Eric’s sons, Greg and Judd; Alan’s sons, Zachary and Benjamin, then Jethro, Nathan, Adam and Eden, who was born just two months ago.

“It’s not a dead picture,” said Robert Lieberman, now 83 and living near Alan in Johannesburg. “It changes anytime someone turns 7.”

Many Liebermans remain in South Africa, while others have scattered to Australia, Canada, the United States and Israel. Most display the collage in their homes, too. When they get together, the Lieberman males always gather for a group photograph, ordered by generation – as they’ll do at Nathan’s bar mitzvah in South Africa this summer. Daughters’ sons aren’t included because they don’t carry the Lieberman name.

Izzy and his wife, Cecilia, had eight children in all. The eight produced 22 children, and the 22 produced 35. Those branches would remain disconnected had Rachel Lieberman not believed that Izzy was alive and set out to find him. She’d kept the tree intact.

Another family member, Kim Lieberman Kapalushnik, recently began a parallel collage — of the family’s girls. It’s been difficult to collect the pictures across the generations, to say nothing of finding images showing the females at age 7, too.

Eric Lieberman, meanwhile, is writing a book about his grandfather’s life. Its tentative title is “Thrown Away” – virtually Izzy’s words upon beginning his journey home.

But the story of the collages of the 7-year-old boys isn’t only a cautionary tale of the ordeal of one child, Eric Lieberman explained. The collages also provide “a sense of how close our family is,” he said.

“It’s an identity with the family, a feeling of closeness, a memory we should all know of what’s handed down from generation to generation,” he said. “People will look at the picture and ask. Everyone asks.”

(Please email Hillel Kuttler if you would like “Seeking Kin” to write about your search for long-lost relatives and friends. Please include the principal facts and your contact information in a brief email. “Seeking Kin” is sponsored by Bryna Shuchat and Joshua Landes and family in loving memory of their mother and grandmother, Miriam Shuchat, a lifelong uniter of the Jewish people.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.