The Seeking Kin column aims to help reunite long-lost relatives and friends.

BALTIMORE (JTA) — Josh Perelman is seeking kin — but not his own. Rather, Perelman is on a quest for families and individuals who will share memories, artifacts and pictures that help tell the story of the American Jewish relationship with baseball.

As chief curator for the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia, Perelman is mounting an exhibition that will open next March. Instead of focusing solely on American Jewish baseball icons such as Hank Greenberg and Sandy Koufax, the exhibit is meant to be grass roots and personal, revealing how Jews connected to this country and to each other through America’s national pastime.

The connections need not be related to professional baseball, Perelman said. They could involve memories such as rushing through dinner to make Little League games, reminiscences of playing ball in Jewish summer camps and displays of team uniforms that were sponsored by Jewish businesses.

When a caller mentioned to Perelman a friend’s b’nai mitzvah at which guests were seated at tables named for Jewish Major Leaguers — including Lipman Pike, considered the first Jewish professional baseball player — Perelman expressed interest in obtaining a seating card from the event.

On a website launched last week by the museum, fans are encouraged to alert the museum to what items they might want to donate or lend, as well as to stories about the person’s connections to baseball.

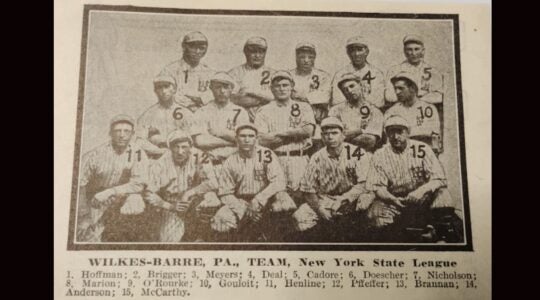

Some items to be displayed in the museum might not relate to Jewish ballplayers at all but will help illuminate the exhibit’s theme, “Chasing Dreams: Baseball and Jews in America.”

For example, Paul Newman of Philadelphia posted photographs of two baseballs that were signed long ago by Pete Rose and Johnny Bench, stars on the Reds’ championship teams in the 1970s. The players personalized their autographs for Newman’s late father, Rabbi Max Newman, of Cincinnati.

Another photo shows former Dodgers pitcher Carl Erskine posing in 2011 with a smiling Rebecca Alpert, a professor of religion and women’s studies at Temple University. Alpert wrote in the post that she “grew up believing that rooting for the Brooklyn Dodgers was what Jews were supposed to do because the Dodgers integrated baseball and represented the working class.”

Erskine had been one of Alpert’s favorite players, and she said she was “thrilled” to meet him at a conference on the Negro Leagues held in Cincinnati, where the picture was taken.

Many of the items that respondents mentioned, posted or offered to the curators relate, of course, to Jewish Major Leaguers: a brilliant color image of a very young Koufax wearing his Brooklyn cap as he delivered a pitch against a backdrop of trees and a blue sky; photos from the 1970s of Washington Senators first baseman Mike Epstein fielding and sliding; and a black-and-white shot of Greenberg with boxing champion Joe Louis, under which the unidentified emailer wrote, “Jews have long regarded themselves as a people on the outside looking in. African-American heroes like Joe Louis and Jackie Robinson have been part of ‘our crowd.’ ”

“The story of Jews in baseball has typically been told by focusing on Major League Baseball, and counting up how many Jews played in Major League Baseball and disputing who’s a Jew and who’s not a Jew: Was Elliott Maddox Jewish? Was Rod Carew Jewish?” John Thorn, the lead consultant for the exhibition, said by telephone. “To me, the far more interesting story was on the other side of the television set: What was the ordinary Jew’s experience with baseball? How did baseball become a binding, integrating, assimilating force in Jewish life?”

Aside from his professional qualifications as Major League Baseball’s official historian, Thorn is in a unique position to examine the issue. Thorn, who is Jewish, was born in a displaced person’s camp in Germany after World War II and settled with his parents in New York. Baseball, particularly the experience of collecting baseball cards, was how the young Thorn made his way in his adopted country — his “visa to America,” Thorn said.

“The story of baseball being more than a game, which is a cliche, of course, resonated for me particularly,” he said.

Up to 200 artifacts will fill the 2,400 square feet on the museum’s fifth floor. After closing at the end of the 2014 baseball season, the exhibit will tour nationally, with smaller versions visiting Jewish community centers, synagogues, historical societies, libraries and stadiums, Perelman said.

Besides the general public, items will come from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, the American Jewish Historical Society and the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History. Bud Selig, the commissioner of Major League Baseball, is among those serving on the advisory committee.

What item would Perelman most like to acquire for display?

A bat, glove or personal item relating to Pike would be nice, he said.

The ultimate catch, though, would be the High Holy Days ticket that Koufax didn’t use after making his celebrated decision to sit out Game 1 of the 1965 World Series against the Minnesota Twins because it fell on Yom Kippur.

“As many shuls as there are in Minnesota, that’s how many claim he was there” to observe the day, Perelman said.

The ticket, Perelman added — his slyness detectable even over the phone — is something “I know doesn’t exist because he didn’t go to services.”

(Please email Hillel Kuttler if you would like “Seeking Kin” to write about your search for long-lost relatives and friends; include the principal facts and your contact information in a brief email. “Seeking Kin” is sponsored by Bryna Shuchat and Joshua Landes and family in loving memory of their mother and grandmother, Miriam Shuchat, a lifelong uniter of the Jewish people.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.