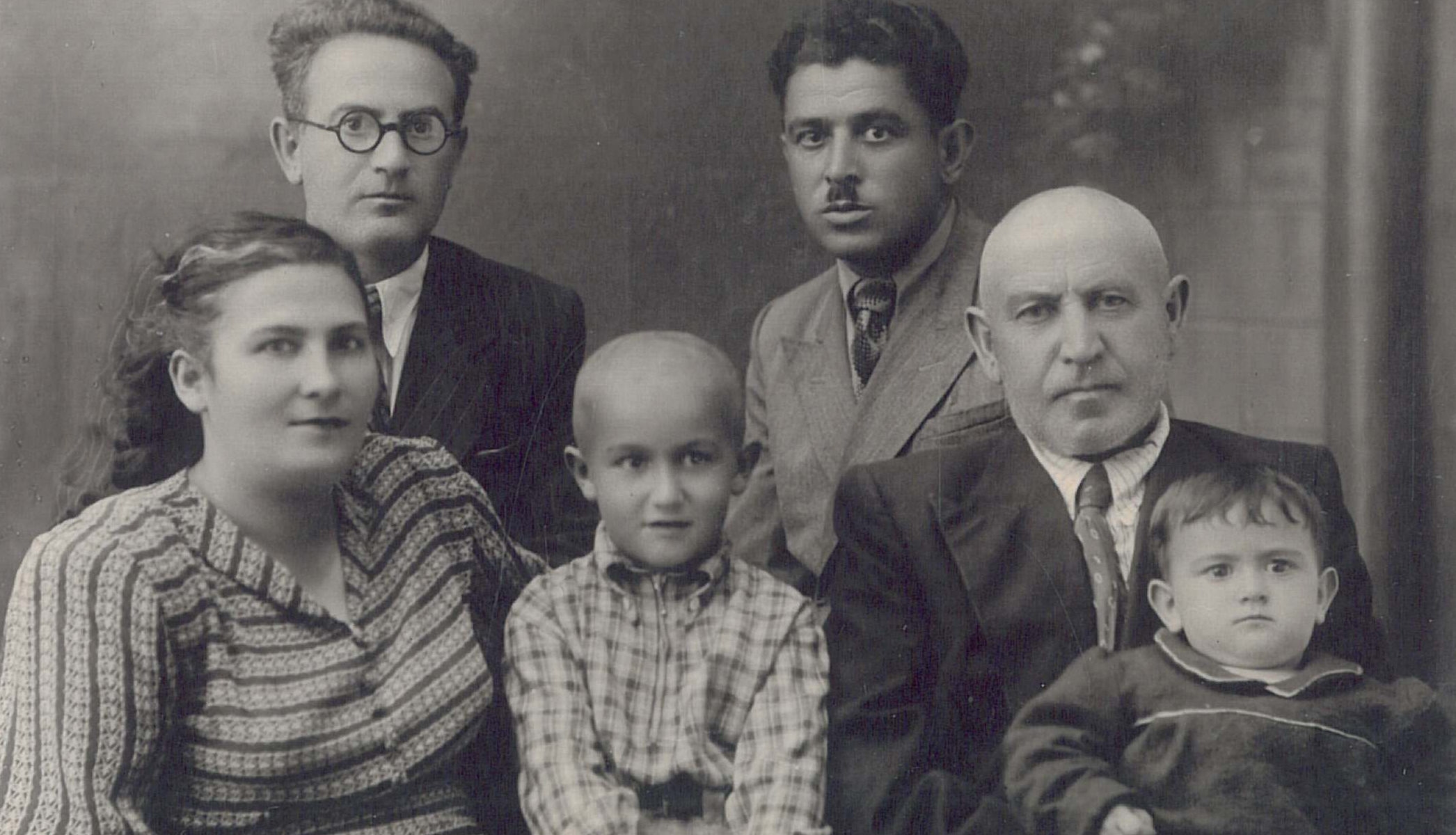

The brother of Morris Greenberg is seen here with his wife, daughter and granddaughter. Sofia Greenberg is hoping her American cousins can identify the people shown. (Courtesy Sofia Greenberg)

The Seeking Kin column aims to help reunite long-lost relatives and friends.

BALTIMORE (JTA) – If only she had a photograph, a location, names — Sofia Greenberg wants to locate American relatives she’s never met.

Greenberg, 61, who lives in the Gilo neighborhood of Jerusalem, hopes to find cousins descended from Morris Greenberg, the brother of her grandfather, Berl. Morris, then called Mordechai, left the family’s home in Novaya Ushitsa, a village in the Kamenets-Podolski region of present-day Ukraine, in 1905 for America. Sofia calculates his birth at 1884 and remembers her late father saying that Morris, once in the United States, owned an auto parts store that made him wealthy, married a Romanian Jewish woman and produced a large family. The father of Morris and Berl — and their other siblings, including at least one brother — was named Mechel.

Where Morris settled, she doesn’t know — only that the locality’s name ended in “wood.”

“I’d like to see them, get to know them,” Greenberg said of her American cousins. Perhaps they have photographs to share or know the name of Berl’s first wife, who died before Sofia was born.

The decades-long transatlantic correspondence between Morris and Berl ended with the Holocaust. Berl Greenberg; his second wife, Rosa; her daughter Riva; and his grandson Shimon fled the Nazis and hid. When he returned to his house after the war, someone else lived there, so he couldn’t retrieve any correspondence and family photographs. Berl, also known as Baruch and Berko, thus lost touch with his brother.

Many of the Greenbergs served in the Soviet military and avoided the Nazis’ clutches, but the family suffered losses, too. Moshe-Shevach Greenberg, Sofia’s father, was away from 1939 through 1945; she even has a photograph showing him posing at the Reichstag following the defeat of Nazi Germany. Moshe-Shevach’s brother, Maor, who was Shimon’s father, also served then in the military and would die post-World War II, while their half-brother, Fishel, was killed in battle.

Their sister, also named Riva, was a military dentist who committed suicide after the war. Another sister, Gittel, died after being struck by a train or trolley before the war. Their stepsister, Rachel, refused to go into hiding with the others and remained in Novaya Ushitsa with her husband; both were killed in the Holocaust.

Of the four who escaped initially, Rosa and Shimon were later captured and killed. Berl and Riva somehow got away and hid again.

After emigrating from Moscow to Israel in 1990, Sofia Greenberg researched her family at Yad Vashem, Israel’s national Holocaust institute. She was put in touch with Riva Tatarskaya, her father’s long-lost stepsister, who moved to Israel in the early 1990s. Sofia also met Riva’s son, Arkadi, and his daughter and two granddaughters. Riva, now 95, has another son, Boris, a cardiologist in St. Petersburg, Russia.

They are Greenberg’s only paternal relatives, along with her brother, Arkadi, who lives in Israel. But no one on her mother’s side survived the Holocaust, she thinks. Indeed, shortly before moving to Israel, Greenberg asked her mother, Rivka-Leah, about a white streak in her hair. Rivka-Leah (who died in 1998) explained that while serving during the war as a military nurse, she learned of her family’s murder. The blow was immediate: The next morning, some of her hair turned white, and it remained so.

Sofia herself nearly was killed once. A decade ago, a bullet shot from the village of Beit Jalla almost struck her during a period of Palestinian attacks. It occurred while she shopped not far from the kiosk where she sells tickets for Mifal Hapayis, Israel’s national lottery. The job is a far cry from her work as an economist in Moscow. She grew up in nearby Kaluga, where Berl (who died in 1974) lived with the family.

She remembers Berl occasionally attending clandestine prayer services at acquaintances’ homes in Kaluga during the period of Soviet repression and the prayer shawls worn by the men at Friday night services in her home.

On Greenberg’s trip to Novaya Ushitsa last May, a woman gave her the 1985 written testimony of a villager who had witnessed the Nazis’ wholesale murder of the Jewish community on Aug. 20, 1942. Greenberg visited the forest where the killing occurred. Standing at the edge of the pits where more than 3,000 Jews were shot, Greenberg considered the hilltop village’s springtime beauty and attractive park of the present.

She tried to comprehend how here, in four pits 10 meters apart, the village’s Jewish life ceased that summer’s day. She considered the testimony’s mention of the teacher recognized by the man in the procession of doomed Jews; the little girl seized from a hiding place and thrown into the line of marchers; the killers cramming each hole as tight as possible before mowing down the occupants; the villagers waiting until the shooting stopped to grab the forsaken clothing at the pits’ edge; the blood-discolored earth; the ground continuing to shake and moan hours later.

Greenberg recently spoke with a Tel Aviv man raising funds for his book about Novaya Ushitsa to be translated into English. She intends to help him memorialize their ancestral village. She also got out the word on the Israeli radio program “Hamador L’chipus Krovim” (Searching for Relatives Bureau).

And she will continue searching for the descendants of her grandfather’s brother, the man who more than three decades before the Nazis marched into Ukraine saved his future family from the pits that swallowed other Greenbergs — a fate he never could have foreseen.

(Please email Hillel Kuttler at seekingkin@jta.org if you know the whereabouts of Morris Greenberg’s descendants. If you would like “Seeking Kin” to write about your search for long-lost relatives and friends, please include the principal facts and your contact information in a brief email. “Seeking Kin” is sponsored by Bryna Shuchat and Joshua Landes and family in loving memory of their mother and grandmother, Miriam Shuchat, a lifelong uniter of the Jewish people.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.