The “Seeking Kin” column aims to help reunite long-lost friends and relatives.

BALTIMORE (JTA) — Like many immigrants from Germany who fought in the U.S. military during World War II, Harry Ettlinger served his adopted country by translating captured materials and interpreting during interrogations of enemy prisoners.

But within that population of soldiers, Ettlinger played a unique role. He was assigned to a little-known department of the Allied forces that located and returned important documents and works of art that the Nazis had taken from public and private collections. The 350-member department operated in small groups attached to military units in Western Europe at the end of World War II and in its aftermath.

Ettlinger, 86, of Rockaway, N.J., is one of six surviving Monuments Men — the male and female members of the Allies’ Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Department — and will receive an award from the American Jewish Historical Society at its Nov. 1 dinner in Manhattan.

Col. Seymour Pomrenze will be honored posthumously at the event for having sent to the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research thousands of documents and other items that the Nazis had looted from Vilna’s Strashun library of Jewish works. Pomrenze also returned Judaica to communities or their former residents, and when that wasn’t possible the treasures, including Torah scrolls and crowns, were given to Jewish museums.

All told, the Monuments Men restored more than 5 million cultural objects to their rightful owners, and they are the model for contemporary restitution efforts relating to Nazi-plundered art, according to the American Jewish Historical Society’s executive director, Jonathan Karp. And their story is about to become much more well known: George Clooney is in Europe directing a movie titled “The Monuments Men” that is due out late next year.

While the Monuments Men helped return items that the Nazis “stole indiscriminately from all sources,” Jews had owned “a disproportionate amount” of the looted art, Karp said.

The department’s mission stemmed from the position taken by the Roosevelt administration’s Roberts Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in War Areas, which Karp summarized as “To the victors do not go the spoils.”

It was “a unique decision in the history of warfare,” he said.

Helping the cause was that many of the Monuments Men were scholars and museum officials themselves, enabling them to identify what the Nazis had stolen from public and private collections. They also were aided by non-Nazi German museum officials.

Ettlinger, however, was not an art expert. Shortly after being shipped to Europe with his U.S. Army unit, he was tapped for duty as an interpreter because he was fluent in German.

A native of Karlsruhe in southwestern Germany, he had moved to the United States with his parents and two younger brothers in late 1938. The Ettlingers spent several months living in upper Manhattan, where the teenage Harry often ascended to the roof of the family’s apartment building to watch Columbia University football games being played at Baker Field below. The family soon moved to nearby Newark, N.J.

His work with Monuments Men began shortly after Ettlinger reached the 7th Army’s headquarters in Munich in 1945. He accompanied an American officer to the jail cell of Heinrich Hoffmann, Adolf Hitler’s personal photographer. Ettlinger interpreted during the prisoner’s interrogation.

In a telephone interview Monday, he recalled that the interrogation centered on Hoffman’s knowledge of the whereabouts of artworks looted by the Nazis.

Ettlinger, a retired mechanical engineer, estimated that 10 of his 13 months with the Monuments Men were spent in the salt mines in Heilbronn-Kochendorf, not far from his hometown. The vast mines, which the Germans had booby trapped, contained 40,000 crates of art, books and other cultural treasures that had been placed there for safekeeping. Each box was marked with numbers and initials corresponding to its museum, library or collection of origin.

“They’d tell me, ‘Harry, get box so-and-so from this art museum and open it up here, and make sure it has this particular painting,” Ettlinger said. The retrieved item or box was then forwarded to a collection point in Wiesbaden or Munich, and on to its rightful home.

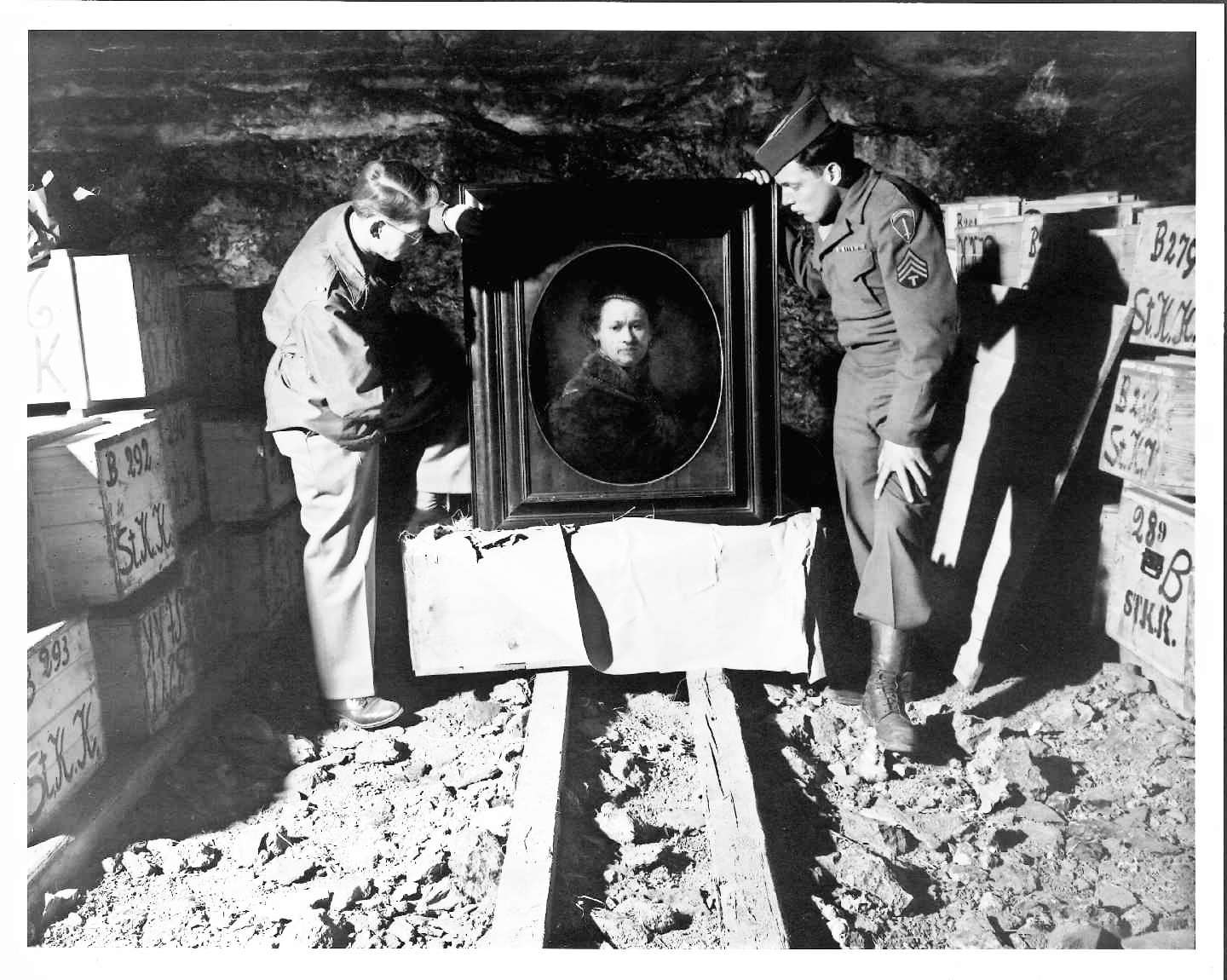

Ettlinger was not personally involved with the repatriation of stolen Judaica, most of which the Nazis stored in Offenbach. But one painting he found has a personal connection to his family: a Rembrandt self-portrait at the Heilbronn-Kochendorf mines that the department would soon return to its owner, the Karlsruhe art museum, which was just a few blocks from Ettlinger’s childhood home. (Ettlinger for this story provided JTA a photo of himself and a Monuments Men colleague, Lt. Dale Ford, inspecting the painting.)

The museum had hidden the Rembrandt and other major works to protect them from possible Allied bombings, according to Tessa Rosebrock, an art historian and provenance researcher at the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe museum.

Praising Ettlinger, Rosebrock said he “did his job in helping his original country, Germany, get better after the war” and in “making a new start.”

Rosebrock said that an agent of Karoline Luise, the duchess of the Baden region, had purchased the Rembrandt at a Paris auction in 1761. It was displayed with other pieces in the duchess’s Karlsruhe castle, forming the basis of the city’s future art museum.

Meanwhile, in 1920, Ettlinger’s grandfather, Otto Oppenheimer, had bought an etching of the Rembrandt. When Oppenheimer and his wife, Emma, fled Germany, their possessions remained behind in a warehouse in Bruchsal, the town north of Karlsruhe where they lived. After completing his military service in 1946, Ettlinger retrieved his grandparents’ possessions and shipped them to America.

Four years ago, Ettlinger was looking through some boxes in search of art. This time the boxes were his, and he smiled broadly upon locating his grandfather’s Rembrandt etching.

The etching now hangs in Ettlinger’s living room. His three children and four grandchildren see it whenever they visit.

(Please email Hillel Kuttler at seekingkin@jta.org if you would like “Seeking Kin” to write about your search for long-lost relatives and friends. Please include the principal facts and your contact information in a brief email. “Seeking Kin” is sponsored by Bryna Shuchat and Joshua Landes and family in loving memory of their mother and grandmother, Miriam Shuchat, a lifelong uniter of the Jewish people.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.