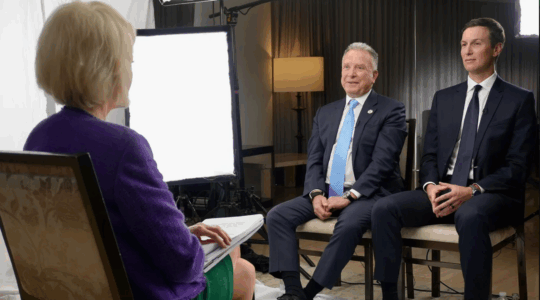

Rami Levy, center, hugging his parents at one of his supermarkets. (Courtesy Rami Levy)

JERUSALEM (JTA) — The corporate offices of Rami Levy, Israel’s nouveau riche supermarket mogul, sit atop one of his grocery stores in southern Jerusalem. It’s not a busy neighborhood, nor is it easily accessible by public transit. But once the building comes into view, there’s no mistaking that it’s his.

Plastered across the side wall in bold letters on a yellow background are the words Rami Levy Hashikma Market. The company name appears at least six more times elsewhere on the building.

Meet the new Israeli mogul – with a net worth about $1 billion, according to Haaretz – whom many Jews outside Israel do not yet recognize, but who is emerging as a champion of the country’s economically struggling families.

Levy, 57, is the owner of the third largest grocery store chain in Israel, with 24 stores across the country en route to the goal of 50. Other competitors have much larger chains, but Levy has gained attention in part by cultivating the persona of a poor boy who made good and now is passing along the benefits to his customers. The benefits include sales and special deals for Jewish holidays, like low prices on matzah for Passover.

Last week, as the cost of bread in Israel rose 6 1/2 percent, Levy’s stores said they would not raise their prices until after Sukkot. Levy’s larger competitors will raise their bread prices after Rosh Hashanah, according to Israeli reports.

“I want the consumer to be happy,” said Levy, a man of few words who sticks to his message. “You want to kill two birds with one stone — to do business so that it’ll be good for the consumer.”

Levy grew up in the crowded Jerusalem neighborhood of Nachlaot, near the open market of Mahane Yehuda. He decided to open his first store when he witnessed a nasty interaction between his grandmother and a shop owner there during one of his furloughs from the Israeli army.

“He didn’t talk to her nicely and it troubled her,” Levy said. He thought, “I’ll get out of the army and I’ll open a store.”

His grandfather owned a small warehouse down the block from the shop owner, on Hashikma Street, a side road in the market that would give his chain its name. In 1977, Levy cleaned, painted and converted the warehouse into a grocery store. He attracted customers by selling food at the same price as his wholesalers.

After three months he connected directly with the companies that supplied his wholesalers and began to buy directly from them, which allowed him to turn a small profit and later to expand his chain.

Levy has since launched an insurance company and a cell phone provider, both of which bear his name. The Israeli business publication Calcalist reported two weeks ago that Levy’s cell phone provider now serves 66,000 customers, compared to several recently launched providers with more than 100,000 customers.

Below his corporate office, attached to the store, customers can also eat at Hashikma Pizza or Hashikma Burger. Levy said he would enter any industry “where I can do well for my customers, sell at low prices and make sure my customers can have good service.”

Customers at the store said they shop there for the low prices, but some other potential buyers prefer the supermarket across the street — a branch of the larger Super-Sal chain. They said they chose to forgo Levy’s deals because his shops are too crowded.

“He wants every meter,” said Moshe Zaken, 29. “You can’t turn the corner. You bump into people.”

Store owners on Hashikma Street, where he began, say he hasn’t changed from the days when they knew him as a friendly and generous grocer.

“He was a nice guy, a regular guy,” said Aviezer Zaken (no relation to Moshe), who runs a fish and poultry shop that like Levy’s chain is named for its owner. “We didn’t expect him to become a billionaire.”

Like a few others, Aviezer Zaken attributed Levy’s success to “the blessing of God. Just the blessing of God.”

Shop owners recalled that although Levy gave free matzah to needy people before Passover, he never gave himself a break.

“What free time? He worked 24 hours a day,” said Yaakov Gazit, who used to own a Turkish restaurant on the corner of Hashikma, near Levy’s store.

Even so, Gazit remembered a night years ago when he was stuck on the other side of Jerusalem with a flat tire and Levy came to assist him at 3 a.m.

“You’re stuck, so I’m helping you,” Gazit recalled Levy saying after Gazit had called for help.

Levy still maintains a storefront on Hashikma whose sign offers food for “cheaper than cheap.” Shop owners there say he comes by every few months, but the interior of the store is empty and some shelves need repairs. Passers-by said it hardly ever opens. The number advertised on the sign does not take incoming calls.

Whether or not God’s hand is guiding Levy’s success, religiously themed pictures of Jerusalem hang in his office and Levy has remained Sabbath observant. Beyond the time he spends that day with his family, his wife — whom he calls “my right hand” — and three of his four children, all adults, work for him. He also has three grandchildren.

“There’s less time one on one because everyone is busy, but we see each other during the day,” he said.

While Levy focuses on his business, he also has become entangled in political controversy. After his West Bank locations in Sha’ar Binyamin and Mishor Adumim began attracting Palestinian customers due to their low prices, the Palestinian Authority discouraged Palestinians from buying there. The PA claimed that patronizing the stores helped the economy of Israel’s settlements, according to The Jerusalem Post.

Still, Levy said, “The people kept buying. I serve my customers regardless of race or nationality.”

He also doesn’t discriminate between Jews and Palestinians when hiring.

“We have a lot of Jews in the Diaspora,” Levy said, so he hopes his hiring practices will prevent people from outside Israel saying to prospective employees, “You are a Jew; I won’t hire you.”

After he expands to 50 stores, Levy said he will have to stop because any additional branches would make his current cost structure unsustainable. Although he “can’t serve all of Israel,” he said he likes to see the larger chains imitate his tactics.

“The moment you blaze a trail and your trail does well for people, and your competitors are doing the same thing, I’m happy,” he said.

Perhaps the opening day of the 50th store will be when Levy takes respite from his never-ending work. What will he do then?

Levy is not talking about retiring, but his former colleague, Aviezer Zaken, said, “He’ll sit on the beach and fish.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.