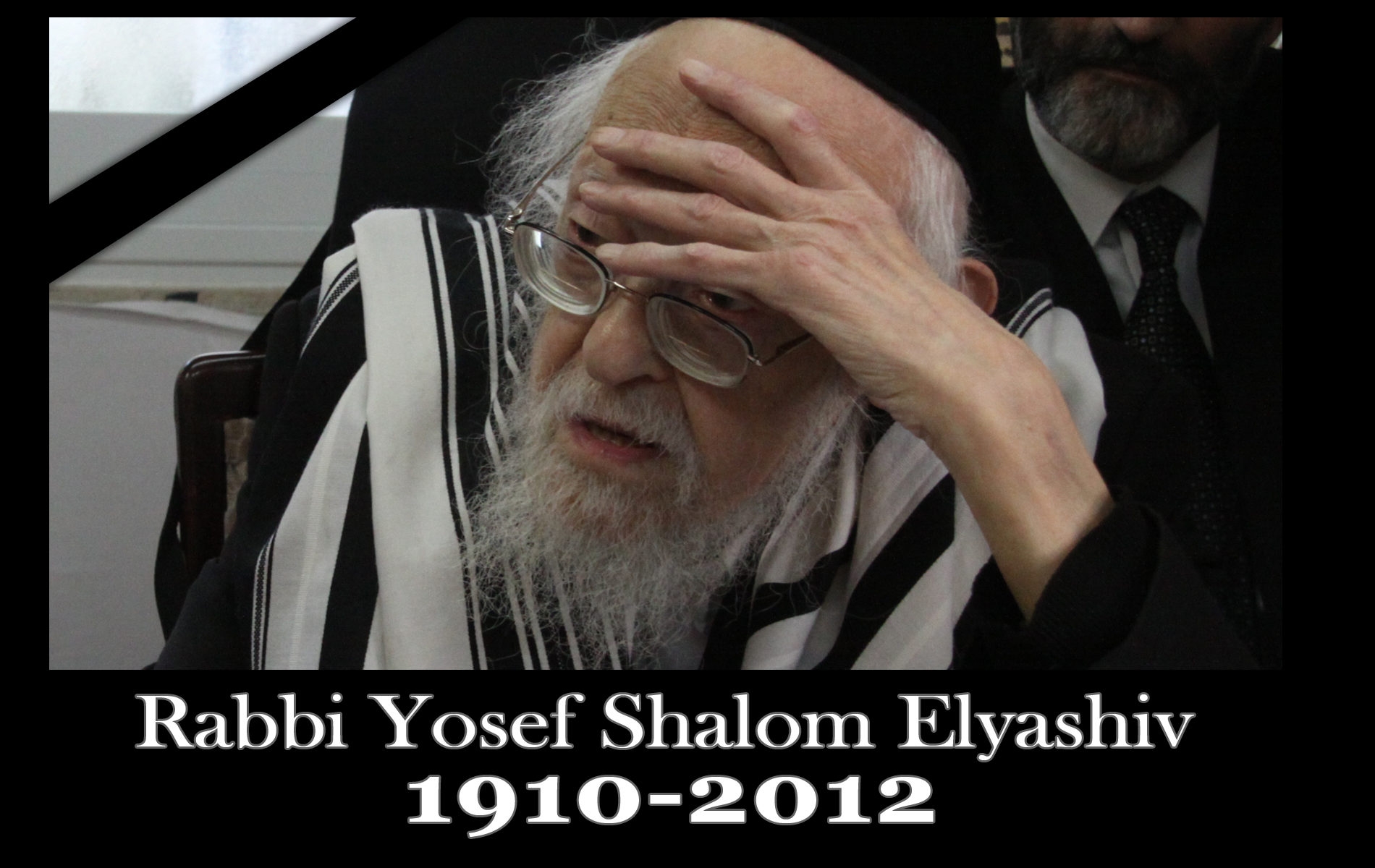

JERUSALEM (JTA) — In an age of sound bites and celebrity seekers, Rabbi Yosef Shalom Elyashiv, who died Wednesday at age 102, represented a world apart.

The head of the Lithuanian haredi Orthodox community in Israel, Elyashiv was a Torah sage who shunned the limelight, dedicating himself single-mindedly to the pursuit of Torah study.

The Lithuania-born Elyashiv, a reluctant leader largely lacking in charisma, was elevated to his preeminent position in the years before the 2001 death of Rabbi Elazar Menachem Man Shach when Shach was no longer able to function. In the haredi community, which is split between Chasidim and misnagdim, Elyashiv occupied the top spot for misnagdim — head of the Ashkenazi, non-Chasidic community known as Litvaks (or Lithuanians).

Unlike Shach — a fiery speaker and an innovative leader who was instrumental in establishing the daily haredi newspaper Yated Neeman and Degel Hatorah, a political party that represents the interests of misnagdim in the Knesset — Elyashiv shunned social contact and communal endeavors. He spent nearly every waking minute sitting alone reviewing the vast body of rabbinical literature and safeguarding haredi Orthodox parochialism through his rulings in the field of Jewish law.

Until February, when Elyashiv was hospitalized in critical condition for congestive heart failure, he was still lucid and authoritative.

“He was answering questions up until the day he was taken to the hospital,” said Rabbi Nahum Eisenstein, an authority on halachah, or Jewish law, who had a close relationship with Elyashiv, who had moved to Jerusalem in his youth.

The non-Chasidic haredi community went to Elyashiv as the final arbiter for any dilemma, not just in the field of religious practice, but also in matters of politics, business and even matchmaking. For the believers who turned to him, Elyashiv’s rulings carried the weight of someone privy to God’s will.

Unlike nationalist, Zionist rabbis who regularly issue rulings in matters concerning the ceding of parts of the West Bank or the proper balance between religion and state, Elyashiv did his best to skirt such matters.

In rare cases, when he was forced to issue a ruling in order to direct haredi politicians on how to vote on a particular issue, Elyashiv seemed concerned primarily with safeguarding haredi Orthodoxy’s parochialism even if it meant taking a dovish position on the West Bank and Jewish settlements.

In 2005, Elyashiv ruled in favor of joining Ariel Sharon’s government, providing it with essential backing ahead of the withdrawal from Gaza Strip and the evacuation of some 9,000 Jewish settlers living there. In exchange, Elyashiv demanded an immediate halt to all attempts to limit the complete the autonomy of haredi educational institutions, including those partially funded by the state. Secular subjects such as math, history and languages are not taught in haredi high schools, something that has hampered the ability of community members to join the job market and perpetuated haredi poverty and reliance on welfare.

Elyashiv also strongly opposed military service for haredi young men — including service tailored to haredi needs — fearing that time spent in a secular environment presented unacceptable spiritual dangers and took away time from Torah scholarship. For similar reasons, he also opposed the growth of institutions providing occupational training for haredi men. He also said women should not work outside the home.

Many Orthodox Jews believe that God ensures that in every generation there is a man of great stature whose decisions reflect God’s will, known as da’at Torah — literally, the opinion of the Torah.

“Rabbi Moshe Feinstein was that man in the previous generation, Rabbi Haim Ozer Grodzinski was before him and so on, going all the way back to the giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai,” Eisenstein said.

Haim Cohen, a haredi political functionary and close aide to Elyashiv, said that “the entire generation” chose Elyashiv as the unrivaled representative of da’at Torah in this generation.

“There are no primary elections for a position like this,” Cohen told JTA. “The rabbi’s strength did not come from any office that he held or from being in a position of power because he did not have any official position. He was simply a man that dedicated himself completely to Torah study, and people recognized and honored this. They simply understood that he was the one.”

But Benjamin Brown, a professor at Hebrew University’s Department of Jewish Thought and a researcher at the Israel Democracy Institute, said that the crowning of Elyashiv — a relatively obscure figure before Shach’s death — was a product of a concerted effort on the part of high-ranking figures in the haredi community.

“Rabbi Shach showed a preference for Rabbi Elyashiv because of his conservatism, and senior journalists at Yated Neeman helped promote him,” Brown said. “Haredi functionaries and politicians started turning to him for advice. A dynamic was created according to which he became gadol hador” — the greatest of his generation.

Whether it was providence or insider politics that brought Elyashiv to preeminence, his rulings in Jewish law reflect a deeply conservative, stringent approach.

In large part due to Elyashiv’s opposition, the Israeli Chief Rabbinate has not instituted the use of prenuptial agreements that could help reduce the agunah problem – women who are “chained” to husbands who refuse to grant them a religious writ of divorce, or “get” – by imposing hefty monthly fines on uncooperative husbands.

In a Passover Haggadah printed with some of Elyashiv’s rulings as heard by his students, parents were warned not to allow daughters older than 3 to sing the Ma Nishtanah in front of men other than their father or brothers because strict interpretations of halachah forbid men to hear women sing.

Elyashiv prohibited haredi institutions from receiving charity from Christians. He ruled that it was forbidden to use elevators on Shabbat, including those preprogrammed to work automatically. He took a stringent position on the halachic definition of death, making it nearly impossible for Jews to donate organs. He permitted the force-feeding of geese for the production of foie gras.

Brown attributed Elyashiv’s extreme conservatism to his limited social contact with the outside world.

Part hagiography, part history, a biography of Elyashiv titled “The Diligent One from Hanan St.” relates that Elyashiv was so completely engrossed in his studies that he did not recall the names of his own children.

His wife, Sheina Chaya, herself the daughter of a prominent rabbi, Aryeh Levin, purportedly did not wake him in the middle of the night when she began labor so as not to disturb his tight study schedule. She died in 1994. The couple had 12 children, including a son who died of illness in childhood and a daughter who was killed by Jordanian shelling in 1948.

Even as a child, Elyashiv was renowned for his perseverance, relentless concentration and detached, logical analysis.

According to one widely quoted anecdote, an elderly haredi Orthodox American man visiting Jerusalem’s Mea Shearim neighborhood in the 1980s asked at the Ohel Sarah synagogue about a boy he remembered from there 70 years earlier. The lad had sat from morning to night learning page after page of Talmud by himself, not lifting his head for even a moment and never playing with the other boys.

“I’ve always wondered what happened to that boy,” the American said.

He was told, “That same boy is still sitting there learning. He has his own key, and he lets himself in and locks the door behind him so he won’t be disturbed.”

That boy was Elyashiv.

In a 30-minute YouTube video, Elyashiv can be seen in his tiny, shabby apartment in Mea Shearim, where he lived since he married, learning Talmud and singing softly to himself without once lifting his eyes from the book.

“I have difficulty explaining to the general public Rabbi Elyashiv’s appeal,” said Kobi Arieli, a haredi writer, commentator and entertainer. “For people unfamiliar with the world of Torah scholarship, it is nearly impossible to convey the reverence and respect a man like Rabbi Elyashiv commands.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.