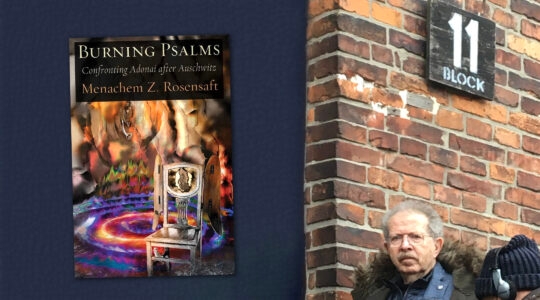

A friendly mah jongg game on the terrace of the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles, June 2012. (Edmon J. Rodman)

LOS ANGELES (JTA) — With a Chinese “bam” and “crak,” and a Jewish “pop,” the real action is happening outside the galleries of the Skirball Cultural Center here. That was by design.

Unlike most art shows, where guards may stand watch to ensure that no one gets too close to the artworks, “Project Mah Jongg” is different: Not only is the central exhibit touchable, it’s playable, too.

At the Skirball through Sept. 2, “Project Mah Jongg” next travels to the Jewish Museum of Florida in Miami Beach in October and then the William Breman Jewish Heritage & Holocaust Museum in Atlanta in April. The exhibit originated at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York.

On a recent afternoon, the distinctive clinking-clanking sounds of mah jongg tiles fill the air of the Skirball. Although the game table sitting in the middle of the exhibition looks inviting, eight players of the rummy-like game of Chinese origin — popular with Jewish players since its U.S. introduction in the early 1920s — prefer to take their friendly games to the terrace, where the museum has set up several mah jongg tables.

The players come from several generations, and the bams, craks and dots — the names for the various suits of mah jongg tiles — are flying.

Before taking a seat at a table, each player had warmed up by taking in the show: a gallery of memorabilia illustrating the game’s place in Jewish pop culture supplemented by more contemporary and humorous interpretations by artists Maira Kalman and Bruce McCall.

One exhibit, titled “Mah Jongg Hostess,” features a mah jongg-themed skirt, gelatin mold and a box of Joya chocolate-covered jelly rings. For the mostly groups of women visiting that day, its accompanying text belabors an already internalized point: “In many households, mah jongg was a ritual created by and for women.”

Jewish women were pioneers in standardizing the game and writing rulebooks, even becoming authorities of the game, the show’s text reminds.

“This is my grandmother’s set. I have it at home. It’s a family heirloom,” Teri Kaufman says, pointing to a vintage mah jongg set with an artificial reptile skin case she found on display. “I remember my grandmother playing with that set.”

Kaufman is visiting the show with members of her Hadassah group — all mah jongg players.

Another display attempts to answer whether Chinese food was the Jewish link to mah jongg, or possibly the other way around. The show’s text explains that Jewish Americans of the 1920s were enthusiastic adopters of immigrant products, including Chinese food.

“Cross-ethnic sampling created a sense of adventure, and demonstrated a sophistication that transcended old-world parochialism,” it reads.

“I am so craving Chinese food right now,” says Nancy Eisman, responding to the Asian motif of the tiles, vintage scorecards and other accouterments of the game.

Ronee Kraves, who is Chinese, encountered the original version of the game while growing up in China. She is doing her own “cross-ethnic sampling.”

“The tiles are the same, and the rules might be different,” she says. “My parents played and I learned from them. When we go back to China, we play.”

Kraves says that until visiting the show, she was not aware that Jews were big players. She points to a large 1924 photo, “Leisure class ladies playing a floating game of mah jongg,” depicting a group of bathing-suited Jewish women playing the game.

“They’re just like the Chinese people who play in the water when it gets hot,” Kraves says.

“The game is a perfect runway to memories,” says the traveling show’s curator, Melissa Martens, director of Collections & Exhibitions at the Museum of Jewish Heritage. “So many people have mah jongg sets buried in their attics or closets.”

On the Skirball deck, several visitors are ready to add to those memories. Assisting them is Lisa Blandford, the Skirball exhibit’s mah jongg facilitator.

“I try to get people to play,” she says. “The tables are usually filled with people who bring their own groups, and sometimes people who have just met each other.”

Players of one game included Necia Sukonig, a veteran who sometimes plays twice a week, and her daughter, Ivy Ransom, as well as Kraves, who after watching a game is ready to try her hand. Blandford, also a newcomer to the game, makes the fourth.

The game, slow at first as players draw tiles and arrange them on racks, quickly picks up speed. They try to achieve mah jongg by using their tiles to match specific sequences of tiles dictated by a game card published by the National Mah Jongg League, a group founded in 1937 by German Jewish women.

“Who has all the jokers?” Sukonig asks as she eyes each player. “You’re a good a bluffer,” she says to her daughter as they cross looks.

The players continue a complicated passing sequence until Sukonig announces, “Mah jongg,” signifying victory.

“At home they would all have to pay me money,” she says in an aside. Many mah jongg games are played for small amounts of money; it’s part of the game’s sociology.

Martens says that each aspect of the game is meant for sharing and community, and that the exhibit “was designed to feature the visitor.”

As a result of the New York museum’s creation and continued involvement with the show, she and some 30 staff members have learned how to play mah jongg, Martens says.

“They have become addicts,” she said.

Exhibit visitor Bonnie Neustein, seated on a couch next to Eisman, observes that mah jongg is about “reaching out to other people, face to face instead of a computer.”

Eisman adds, “It will be interesting to see if a younger generation can sit still long enough to play.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.