One of the most remarkable friendships in Jewish history was between my father, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, and Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

When they met in 1963, they felt an instant bond, despite the enormous differences in their backgrounds: Dr. King was a Baptist minister from the segregated South, trained in Protestant theology at Boston University. My father was a Jewish theologian, trained as a scholar in Germany, raised in an intensely pious, chasidic milieu in Warsaw; indeed, he was supposed to become a chasidic rebbe in Poland. What brought them together was a piety that transcended differences, forged by their love of the Bible, especially the prophets.

Their friendship was stoked by mutual concerns and tremendous public courage. My father spoke passionately against racism, and he engaged African-American theologians and social thinkers in dialogue, listening to their experiences. He worked together not only with Dr. King, but also with Jesse Jackson, Albert Cleague, Andrew Young and others. Dr. King, through his friendship with my father, spoke out vociferously on behalf of Soviet Jews, in support of the State of Israel and against the war in Vietnam.

For both men, these were biblically based positions, and the similarities in their understandings of the Bible are striking. Both believed that God is affected by human deeds, and both rejected Aristotle’s influential insistence that God is unaffected by human beings — an “unmoved Mover.” On the contrary, God is “the most moved Mover,” both men used to say. That is the lesson of the prophets: that God cares deeply about human beings and is pained by human acts of injustice and cruelty.

Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington in 1963. Getty Images

Like the prophets and Dr. King, my father spoke with passion. Racism was not simply wrong, it was evil: “Few of us seem to realize how insidious, how radical, how universal an evil racism is. Few of us realize that racism is man’s gravest threat to man, the maximum of hatred for a minimum of reason, the maximum of cruelty for a minimum of thinking.” Dr. King’s 1967 speech against the war in Vietnam was deeply courageous, and he was bitterly attacked for it, including by other civil rights leaders, who thought he should keep quiet about the war, that it was not a civil rights issue. Yet Dr. King, who stated dramatically, “A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.” Economic injustice was a tool of racism, my father and Dr. King agreed, the creation of an unequal society, and in such a wealthy country, poverty was sheer cruelty.

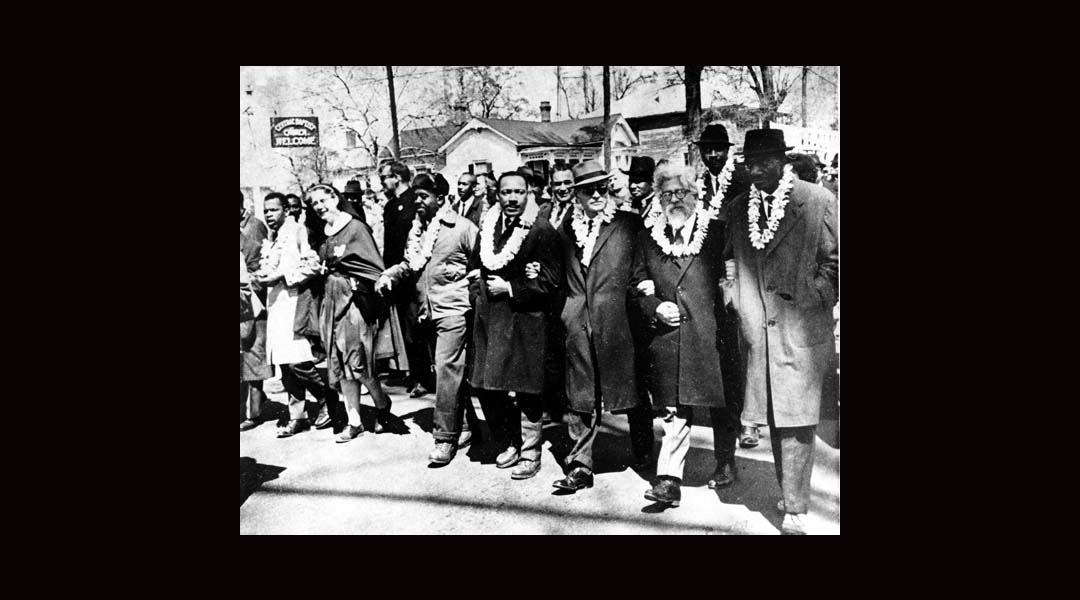

For many Jews, the photograph of my father in Selma with Martin Luther King at the start of the Voting Rights March of 1965, both men adorned with Hawaiian leis, is an iconic picture. Jews are inspired by the image, and also feel affirmed: it is indeed our Hebrew prophets who made justice central to God’s message. Andrew Young once told me that many civil rights workers carried copies of my father’s book on the prophets in their pockets as they marched.

Indeed, on several occasions President Barack Obama has quoted my father’s words when he returned from Selma: “I felt my legs were praying.” Just as African Americans remember my father’s bravery and the gift of his presence at Selma, we Jews continue to affirm the centrality of justice to the message of Judaism.

The last time we were with Dr. King was when he spoke to a Rabbinical Assembly convention at the Concord Hotel in March of 1968, at a gathering of rabbis honoring my father. As Dr. King entered the hall, the rabbis stood up, linked arms and sang “We Shall Overcome” in Hebrew, as a tribute to him. In introducing Dr. King to the rabbis, my father asked, “Where in America today do we hear a voice like the voice of the prophets of Israel? Martin Luther King is a sign that God has not forsaken the United States of America.” A few weeks later, Dr. King was hoping to join my family for the Passover seder; instead, that terrible spring, my father read a psalm at Dr. King’s funeral.

As another Martin Luther King Day approaches, I think it’s necessary to pause and imagine what that seder discussion might have been like. What would each have contributed from his religious tradition? Could you imagine their amazement and their tears of joy had they lived to see Americans transcend the racism of our country and elect an African-American president?

My father’s words about Dr. King should remind us that each Jew can be a prophetic voice, an echo of the prophets of Israel from whom we are descended. He would have wanted us to end the bitterness that often poisons our political debates and join together in overcoming enmity, selfishness and injustice. Perhaps he would have enjoined us to finally accomplish what the prophets demand, and create the society that would make them proud.

Susannah Heschel, Eli Black Professor of Jewish Studies at Dartmouth College, has recently published a new collection of her father’s essays, “Essential Writings of Abraham Joshua Heschel” (Orbis Books).

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.