This April, the Schocken / Nextbook Jewish Encounters series will publish “Sacred Trash: The Lost and Found World of the Cairo Geniza” by Adina Hoffman and Peter Cole, which tells in dynamic fashion the story of the retrieval of what has often been called the greatest discovery of Jewish manuscripts ever made. “No longer can we speak of the seven wonders of the world —” Cynthia Ozick has written of the Geniza and of “Sacred Trash.” “In this astounding and acutely relevant tale, Adina Hoffman and Peter Cole have uncovered a remarkable eighth; and in its connection to our own humanity, it surpasses all the rest.” What follows is a small piece of that wondrous story.

In December of 1896, the charismatic, redheaded, Romanian-born Talmud scholar Solomon Schechter made his way to Egypt. He was hot on the trail of a certain long-lost manuscript. His search took him to the Ben Ezra Synagogue of Old Cairo, and what he found there astonished him.

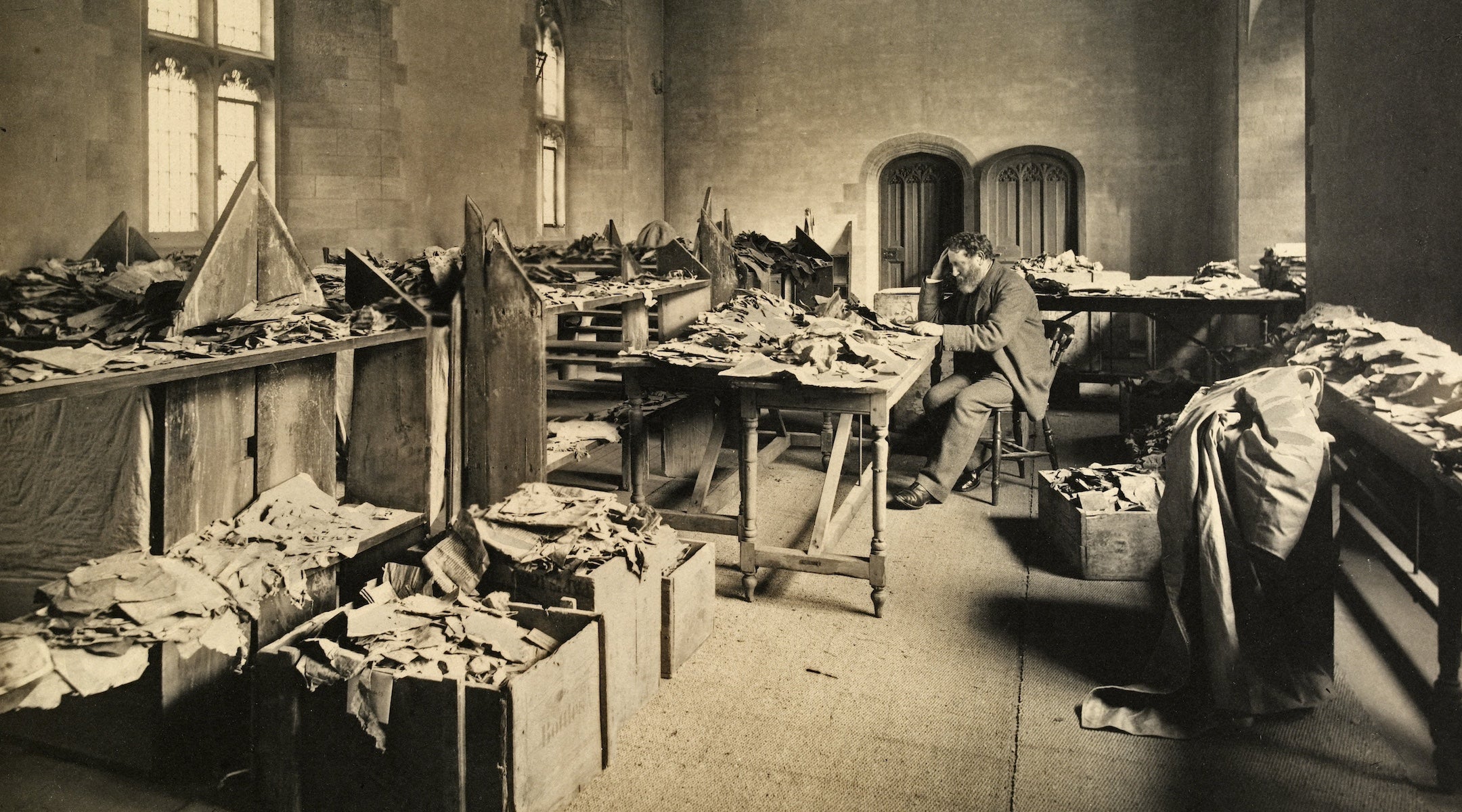

After climbing a rickety ladder to reach the dim, attic-like opening behind a wall in the women’s section, and once his widening eyes had adjusted to the dark, Schechter found himself staring into a space crammed to bursting with nearly 10 centuries’ worth of one Middle Eastern, mostly middle-class Jewish community’s detritus. Crumpled and crushed before him were that community’s letters and poems, its wills and marriage contracts, its bills of lading and writs of divorce, its prayers, prescriptions, trousseau lists, money orders, amulets, rabbinic responsa, contracts, leases, magic charms and receipts. “A battlefield of books,” Schechter called it, and at first glance it must have seemed an unlikely (and unsightly) mess.

It took, in other words, real imagination on Schechter’s part to grasp what faced him in that unprepossessing room. But grasp it he did: in the dank and musty chaos, Schechter soon came to understand that he had uncovered no less than a cross section of an entire society, and one that lay at the very navel of the medieval world — linking East and West, Arab and Jew, the daily imprint of the sacred and the venerable extension of the profane.

Such was the miraculous nature of what has come to be known as the Cairo Geniza that some have compared its discovery to that of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The Cairo Geniza, goes this argument, is actually the more important find, since the sensational, ancient scriptures from Qumran were — as most scholars have seen them — a cultic aberration, “the work of men who gave up the world … to find God in a wilderness”; the Geniza, on the other hand, embraces and embodies the world as it really was, warts and wonders alike, for the vast majority of medieval Jews. One of the 20th century’s greatest historians, S. D. Goitein, whose writing about the daily and most mundane Geniza documents unfurled a vibrant panorama of this Mediterranean society, clearly had such a comparison in mind when he titled a 1970 talk about the Geniza “The Living Sea Scrolls.”

*

“Geniza” is a barely translatable Hebrew term that holds within it an ultimate statement about the worth of words and their place in Jewish life. While the expression itself doesn’t appear in the Bible, several of the later biblical books contain a handful of related inflections: Esther and Ezra, for instance, speak of ginzei hamelekh or ginzei malka — “the King’s treasuries” and the “royal archives.” Rabbinic usage of the root is more common, if also more peculiar: in the Talmud it almost always suggests the notion of “concealment” or “storing away” — though just what that entailed isn’t usually specified.

Writing the sages deemed somehow heretical should, some believed, be ganuz, that is, censored in the most physical manner — by being buried. Likewise, religious manuscripts that time or human error has rendered unfit for use cannot be “thrown out,” but rather “require geniza” — removal, for example, to a clay jar and a safe place, “that they may continue many days” and “decay of their own accord.”

Implied in this latter idea of geniza is that these works, like people, are living things, possessing an element of the sacred about them — and therefore when they “die,” or become worn out, they must be honored and protected from profanation. “The contents of the book,” wrote Solomon Schechter, “go up to heaven like the soul.” The same Hebrew root, g-n-z, was, he noted, sometimes used on gravestones: “Here lies hidden (nignaz) this man.”

The origins and otherworldly aspects of the institution aren’t the only mysterious things about it. Both its development and its precise nature have remained curiously elusive. What we do know is that at some point the verbal noun “geniza” evolved from indicating a process to also connoting a place, either a burial plot, a storage chamber or a cabinet where any damaged or somehow dubious holy book would be ritually entombed. In this way, the text’s sanctity would be preserved, and dangerous ideas kept from circulating. Or, as one early scholar of the material neatly put it: “A geniza serves … the twofold purpose of preserving good things from harm and bad things from harming.”

With modifications, the practice of geniza has continued throughout the Jewish world into the present, ranging greatly from community to community. A nook near or under the synagogue’s ark, a basement room, a cubbyhole — all could and did function as genizot. In some towns and cities, the geniza materials were taken out of their receptacles on a designated day and buried in an elaborate ritual that was part funeral, part carnival.

Depending on local tradition, the papers and books would be placed in straw baskets, leather sheets or lengths of white cloth, like shrouds. Coffins draped with decorative fabrics were sometimes used to hold a no-longer-valid Torah scroll, and the privilege of pallbearing was bestowed upon those who had donated money to the synagogue. Songs were sung, cakes eaten and arak was drunk as a procession set out for the cemetery.

For reasons that remain obscure, in the case of the Palestinian Jews of the Ben Ezra Synagogue, the tradition of geniza was, it seems, extended to include the preservation of anything written in Hebrew letters, not only religious documents, and not just in the Hebrew language. Whatever the explanation for this practice, for most of the last millennium, hundreds of thousands of scraps were tossed into the Ben Ezra Geniza, which came to serve as a kind of holy junk heap.

The materials of the so-called classical period of the Geniza alone (the later 10th through mid-13th centuries) have occupied scores of scholars for more than a hundred years, transforming in the most fundamental way how we might understand Jewish history, leadership, literature, economics, marriage, charity, prayer, family, sex and almost every other subject imaginable — from the nature of the silk trade to astrology, religious dissent, Hebrew grammar, glassmaking and medieval attitudes toward death.

There is, in point of fact, no other premodern period of the Jewish past about which we have so many and varied details. Because of the Geniza, we can nearly hear and see — and often almost smell and touch — the urbane world of the Arabized Jews who populated Old Cairo, or Fustat. If one is used to thinking of Judaism as a straight shot from the Bible to the shtetl, followed by a brief stopover on the Lower East Side, it may seem strange to realize that this socially integrated Jewish society was not just a product of some peculiar local circumstance but was, instead, emblematic of its epoch.

Lest we forget, from the time of antiquity until around 1200, over 90 percent of the world’s Jewish population lived in the East and, after the Muslim conquest, under the rule of Islam. Fustat was, in its medieval heyday, home to the most prosperous Jewish community on earth, and served as a commercial axis for Jews throughout North Africa and the Middle East, and as far away as India. At the same time, the city contained nearly every race, class, occupation and religious strain the region had to offer. “It was,” as Goitein saw it, “a mirror of the world.”

From “Sacred Trash: The Lost and Found World of the Cairo Geniza,” to be published in April by Nextbook/Schocken. Reprinted courtesy of Schocken Books, a division of Random House, Inc. Copyright (c) 2011 Adina Hoffman and Peter Cole.

Adina Hoffman is the author of “House of Windows: Portraits from a Jerusalem Neighborhood” (Steerforth Press) and “My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness: A Poet’s Life in the Palestinian Century” (Yale University Press), which was named a best book of 2009 by the Barnes & Noble Review. Peter Cole’s most recent book of poems is “Things on Which I’ve Stumbled” (New Directions). His many volumes of award-winning translations include “ The Dream of the Poem: Hebrew Poetry from Muslim and Christian Spain, 950–1492” (Princeton University Press). He was named a MacArthur Fellow in 2007. Hoffman and Cole live, together, in Jerusalem and New Haven.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.