When the historian Rebecca Kobrin began researching her book “Jewish Bialystok and Its Diaspora,” which came out this spring, she was struck by the strange way Eastern European Jewish immigrants used words like “exile” and “diaspora.” Between 1880 and 1914, when most of America’s Jews came over from Europe, they did not speak about exile in terms of Israel, as we often do now. They used those words instead in relation to the places they actually left: Bialystok, Vilna, Warsaw, Lodz.

“We have this impression that Jews have always felt exiled from the land of Israel,” Kobrin, a professor at Columbia, said in a recent interview. “But that’s ahistorical.” She added, “East European Jewry did not always use the term ‘galut’” — Hebrew for “exile” — “to refer to their exile from Israel. They used it to describe their personal feelings of displacement from their lived homeland.”

That is a central arguement of her book, which she will speak about at the Center for Jewish History and Bookculture this week. But one of her underlying motives, and one shared by many of her colleagues, is to wrest Jewish history from the maw of communal Jewish issues. Kobrin is careful to note, however, that her work is not politically motivated, only that it is framed in contrast to the present. “I have no comment on Zionism or Israel today,” she said. “Rather, I hope my book captures a world of East European Jewry a century ago.”

The collapse of the Soviet Union was supposed to usher in a new understanding of Jewish history. Materials that scholars had been unable to view for decades were now available for the first time. But it is not the lack of sources that is preventing them from successfully recasting the history of Eastern Europe’s Jews, which made up more than 99 percent of world Jewry before the First World War.

Many historians now view the stubborn hold of contemporary Jewish politics as the main impediment. Israel, the Holocaust and anti-Semitism — touchstones of contemporary Jewish politics, as well as popular history, or what academics call “memory” — have stymied an accurate portrayal of the Jewish past in ways historians never thought possible.

“American [Jewish] memory is constituted by two things,” said ChaeRan Freeze, a professor of East European Jewry at Brandeis, “the Zionist master narrative and nostalgia. We’re trying to revise that.”

By “Zionist master narrative,” she was referring to Israeli or Zionist historians who, in the past, have emphasized the bleakness of Eastern European life in order to justify the need for a Jewish state. Freeze stressed that, for American Jews, an idealized, simpler shtetl life, sentimentalized in works like “Fiddler on the Roof,” is the more dominant misconception. Still, both images are in large part shaped by the Holocaust and the imperatives of a Jewish state. Yet whatever the case, historians feel it difficult to break through these still-too-popular myths.

“What you’re touching on is the most sensitive nerve-endings of Jewish memory,” said Steven Zipperstein, a professor of Russian Jewish history at Stanford. He added, “It’s not as if there isn’t any veracity to the popular perception,” but many popular conceptions “are not sufficiently accurate. And that’s where historians fit in.”

One of the most hotly contested issues to emerge is whether pogroms were the most compelling factor leading Jews to emigrate from Europe.

Zipperstein, who is now writing a cultural history of Russian Jewry to be published by Houghton Mifflin, echoed many of his colleagues when he argued that pogroms were not nearly as common as believed. Of the roughly 2.5 million Jews who left Eastern Europe between 1880 and 1914 — 70 percent of whom came to America — most immigrated for economic reasons.

There is still debate about whether Jews came to America because it offered ample economic opportunity, especially as its economy took off after the Civil War. Or whether it was mostly discriminatory policies in czarist Russia that pushed them there, like the May Laws of 1882, which prohibited Jews from buying land outside the Pale of Settlement. But “by and large,” Zipperstein said, “the economic motive was the main reason Jews left up until the First World War.”

Zipperstein’s own research has focused on the notorious Kishinev pogrom in 1903, where 49 Jews were killed in two days of looting. The event was sparked by an accusation of the anti-Semitic blood libel, and was quickly seized on by the Western media. It was only after Kishinev that the word “pogrom” even entered the mainstream discourse.

But Zipperstein argues that the Kishinev pogrom, particularly in its basis on a medieval blood libel myth, was a rarity. More than 800,000 Jews had left Eastern Europe before the Kishinev pogrom, and the ones who did mostly left small, economically depressed towns that had never experienced anti-Semitic violence.

Nonetheless, Kishinev “became for the much of the world at the time one of the most resonant symbols of Jewish oppression,” Zipperstein said.

Pogroms remain a symbol today of the Old World for an important reason, too — the Holocaust. Most historians agree that the annihilation of the Eastern European Jews, the apogee of European anti-Semitism, now overshadows all understanding of history that precedes it.

Moreover, Jewish historians who were writing the history of pre-Soviet Russia were killed in the Holocaust, leaving popular culture — from the Bernard Malamud’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Fixer” (1966) to Roman Vishniac’s “A Vanished World (1983) — to fill the gap.

Though anti-Semitism was unquestionably a fact of East European life, scholars are now at pains to show how it was only one factor causing Jews to immigrate, and one mainly exacerbated by deeper societal changes.

“The serious point is that we continue to prefer the mythology of the shtetl at the expense of the modern history of Eastern European Jewry,” said Olga Litvak, a professor of Russian Jewish history at Clark University. She will be contributing an essay on modern Eastern European Jewry for an upcoming eight-volume history of Judaism to be published by Cambridge University Press.

Like many scholars working on the period, Litvak emphasized that in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, Eastern Europe was beset by rapid modernization and political upheavals. As in other industrializing countries, Jews migrated to new cities looking for work, often joining revolutionary movements, like socialism, that were part of progressive, modernizing politics. Non-Jews left out of this modernizing process lashed out against Jews, and anyone else who was associated with change.

Even Yehuda Bauer, a prominent historian of the Holocaust, whose latest book, “The Death of the Shtetl,” will be published in paperback this month, made this point in an interview from Israel. “The major causes [for immigration before the First World War] were the penetration of modernity,” he said.

He was not, however, skittish about highlighting the pernicious reality of pogroms. During the Russian civil war that ensued after the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917, about 60,000 Jews were killed in a series of anti-Semitic riots in the following two years.

“The problem,” Bauer said, “is that we remember the wrong pogrom,” referring to Kishinev. Pogroms become a motivating factor for Jews to flee Eastern Europe mainly after the First World War, he said, not before it. But it is before 1914 that the vast majority of America’s Jews arrived.

Still, many historians voiced concerns that anti-Semitism is now being minimized perhaps too much. “I think there is a concern that the new generation wants to blow off anti-Semitism,” said Freeze, of Brandeis. “There is a sense that among younger scholars, they too easily dismiss or downplay anti-Semitism. [They feel] it’s an old-topic,” she added.

But even Freeze said that her own work tries to move past anti-Semitism as the main prism through which to view Eastern European life. She is currently putting together a book of court documents from czarist Russia, which she is co-editing with the Harvard scholar Jay M. Harris and will be published by Brandeis University Press next summer.

She highlighted one official document that listed an attack against a Jewish fruit salesman in the late-19th century as “an act of anti-Jewish violence.” But the facts of the case itself reveal that it was essentially about the salesman’s decision to raise the price of his plums. “If you paint it just as anti-Semitism,” Freeze said, “you miss the nuance of the situation. It doesn’t tell you anything.”

Historians are increasingly taking their case to the public as well. Antony Polonsky, a historian at Brandeis who published the second of a three-volume history of Eastern European Jewry earlier this year, said he is working on a shorter version for a wider audience. “I think we need to popularize our work,” he said. But he was fully aware that overcoming popular misconceptions was a formidable task. “I’m not sure how one does this well,” he said.

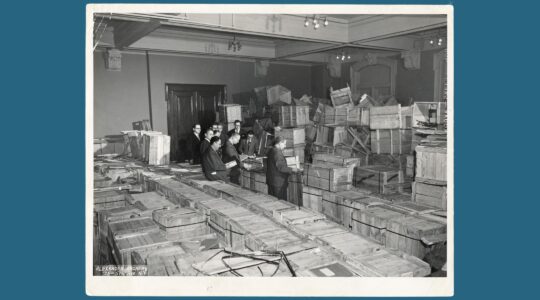

The Yeshiva University Museum, located inside the Center for Jewish History, opened a new exhibit recently titled “16 mm Postcards: Home Movies of American Jewish Visitors to 1930s Poland,” which paints a picture of pre-Holocaust Poland strikingly more modern that than traditional image of “the shtetl.”

This summer, the “YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe” launched its free website, with hundreds of short, jargon-less articles written by scholars, as well as archival material. The purpose, said Gershon David Hundert, the chief editor of the encyclopedia, and a professor at McGill University, is “to make sure that [the history of Eastern Europe’s Jews] does not get reduced to Tevye and a guy in a black hat and beard.”

Still, he conceded that after public lectures he gives on his own, people often confront him confounded, confused or even angry. “You have people talk about their ancestors who came to North America in the 19th century and how they escaped pogroms in Vilna,” he said. He tells them politely that that is not possible. There were pogroms in Vilna in 1918, but in 19th-century Vilna, “there were no pogroms.”

Rebecca Kobrin will be speaking Monday, Nov. 8, 3 p.m., at the Center for Jewish history (15 W. 16th St., [917] 606-8290) and Tuesday, Nov. 9, 7 p.m., at Bookculture (536 W. 112th St. [212] 865-1588). Both events are free.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.