When I was 3, I had a 10-year-old brother, and deep in my heart I hoped that when I grew up, I’d be just like him.

Not that I stood a chance. My big brother had already skipped two grades and had an enviable understanding of everything, from atomic physics and computer programming to the Cyrillic alphabet. Around that time, my brother began to develop a serious concern about me. An article he read in Haaretz said that illiterate people are excluded from the job market, and it bothered him very much that his beloved 3-year-old brother would have a hard time finding work.

So, he began to teach me reading and writing using a unique technique he called “the chewing gum method.” It worked as follows: My brother would point to a word that I had to read out loud. If I read it properly, he gave me a piece of un-chewed gum. If I made a mistake, he stuck his chewed gum in my hair. The method worked like magic, and at the age of 4, I was the only kid in nursery school who knew how to read. I was also the only kid who, at least at first glance, looked like he was balding. But that’s another story.

When I was 5, I had a 12-year-old brother who found God and went to a religious boarding school, and deep in my heart I hoped that when I grew up I’d be just like him. He used to talk to me about religion a lot. And I thought that the midrashim he told me were the coolest things in the world. He was the youngest pupil in the school — because of all that grade-skipping he did — but everyone admired him. Not because he was so smart — somehow, that was less important in the boarding school — but because he was so good-natured and helpful. I remember visiting one Purim, and every pupil we met thanked him for something else: one for helping him study for a test, another for fixing a transistor so he could listen secretly to heavy metal, still another for lending him a pair of sneakers before an important soccer game.

He walked around that place like a king who was so modest and dreamy that he didn’t even know he was regal, and I followed in his wake like a prince all too aware of his royalty. I remember thinking then that the whole business of believing in God would be part of my future too. After all, my brother knew everything, and if he believed in the Creator, then there had to be one.

When I was 8, I had a 15-year-old brother who left religion and went to college to study mathematics and computer science, and deep in my heart I hoped that when I grew up I’d be just like him. He lived in an apartment with his bespectacled girlfriend, who was 24, an age which, from my childish perspective, seemed ancient. They used to kiss and drink beer and smoke cigarettes, and I was always sure that if I played my cards right, in another seven years, I’d be there. I’d sit on the grass at Bar Ilan University and eat grilled cheese sandwiches from the cafeteria. I’d have a bespectacled girlfriend too, and she’d kiss me, tongue and all. What could be better than that?

When I was 14, I had a 21-year-old brother who fought in the Lebanon War. Lots of my classmates had brothers who fought in that war. But mine was the only one I knew who wasn’t in favor of it. Even though he was a soldier, he never thrilled to the idea of shooting guns and throwing grenades, and especially not to the need to kill the enemy. Most of the time, he did what he was told, and the rest of the time he spent in military courts.

When he was tried and found guilty of “behavior unbecoming an IDF soldier” after he turned an aerial antenna into a giant totem pole with a head and eagle’s wings, my sister and I sneaked into the remote base in the Negev where he was confined. We spent hours playing cards with him and another soldier, Mosco, who was also confined, but for slightly less creative reasons. And as I watched my brother in his army pants, his torso bare, paint a water-color picture of the wadi that ran below the base, I knew that that’s just what I wanted to be when I grew up: a soldier who, even in uniform, never forgets his free spirit.

Years have passed since I sneaked onto my brother’s base. In that time, he managed to get married and divorced, and married again. He also managed to work at successful high-tech companies and leave them so he could dedicate himself, together with his second wife, to the kinds of social and political activities that reporters like to call “radical” — things like fighting against biometric records and police brutality and for human rights and legalizing marijuana. In that time, I also managed to grow and change so that, apart from the love we’ve always felt for each other, the only constant in our relationship has been the seven-year difference between us. Throughout that long journey, I never got to be more than just a little of what my brother was, and at some point I guess I even stopped trying. Partly because my brother’s strange route was a very difficult one to follow and partly because I’ve had my own personal crises and confusions to deal with.

For the past five years, my big brother and his wife have lived in Thailand. They build Internet sites for Israeli and international organizations that are tying to make our world a little bit better, and with the modest fee they get for their work, they manage to live very well in their cozy apartment in the town of Trat. They don’t have an air conditioner, a bathtub or a toilet with running water, but they have lots of good friends and neighbors who make the most delicious food in the world and are always happy to visit or host them. Four weeks ago, my wife, our 4-year-old son, and I flew to see their new home. While we were there, we took an elephant tour, and on it my brother’s elephant was a few steps in front of mine. Both were being driven by experienced Thais. After we had gone a few hundred yards, I saw my brother’s driver signal that my brother should take over leading their animal. The Thai man moved to sit to the rear of the elephant and my brother began taking charge. He didn’t yell at it or kick it lightly the way the local driver had. He just bent forward and whispered something in the elephant’s ear. From where I was sitting, it looked as if the elephant nodded and turned in the direction my brother wanted. And at that moment it came back to me — the feeling I’d had throughout my childhood and teenage years. That pride in my big brother and the hope that when I grew up, I’d be a little bit like him, able to drive elephants through virgin forests without ever having to raise my voice.

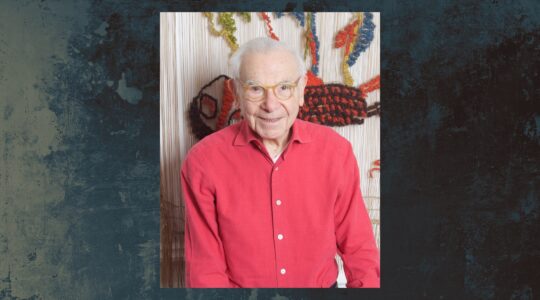

Etgar Keret is the author of “The Bus Driver Who Wanted to Be God,” “The Nimrod Flipout” and “Missing Kissinger.” He is the director of the film Jellyfish. Reprinted from Tabletmag.com. Translated by Sondra Silverston.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.