HENDERSON, Nev. (JTA) — Up in the Catskills, a man named Yossi Zablocki is trying to save the last blintz palace of my generation’s youth. The place is called Kutsher’s Country Club.

Once, in another world, I spent a lot of time there covering basketball players and boxers in training for their big fights and sports clinics that drew 500 high school and college coaches from all over the country for a week each summer to study under coaching giants like Red Auerbach, Nat Holman, Ara Parseghian and Adolph Rupp.

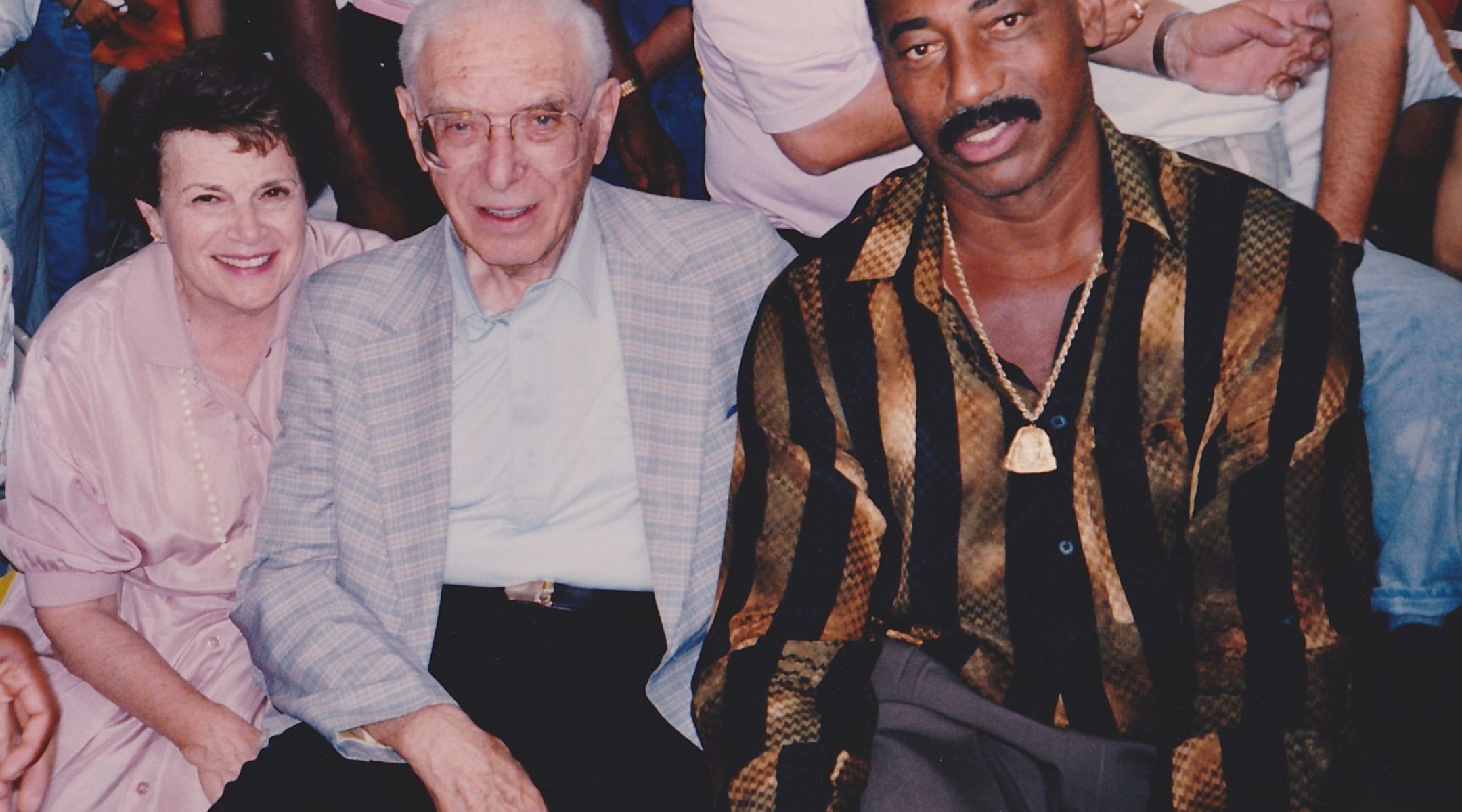

The man who made it all work was named Milton Kutsher.

It was also a time when that slice of the world, comprised of a great wall of kosher hotels affectionately known as the Borscht Belt, had its own lifestyle, bringing with it a ritual of family summers that didn’t need jet air travel or Caribbean beaches or the green felt tables of Las Vegas.

This was the world of stomach-bending meals, group activities, games of “Simon Says,” Latin dance lessons and stages that served as the training grounds for future giants of comedy.

And the soft, summer evenings were punctuated from one end of the “Jewish Alps” to the other with the steady thump, thump, thump of basketballs dribbled against asphalt and the perfect punctuation mark of the swish as the ball arched through the net.

Everybody had a team of pseudo busboys and bellmen straight off college campuses. Who could ever forget the sight of the world’s tallest bellhop out of Philadelphia — a man named Wilt Chamberlain — and a surrounding cast of players featuring talent like Frank Ramsey, Cliff Hagen and Neil Johnson?

But all of that pales against the memory of what Milton Kutsher put together with the Maurice Stokes Basketball Game, a charity game to benefit needy members of the basketball community.

The story begins in 1958 on an airplane bringing the then-Cincinnati Royals home from Detroit, where they had been seven-point losers to the Pistons in the first of a best-of-three, opening-round NBA playoff series.

The plane was more than halfway to Cincinnati when Maurice Stokes, a man with a spectacularly impressive body and who, at 6-feet-7, had been the NBA’s third best rebounder, suddenly collapsed.

That he did not die right there on March 15, 1958 was the direct result of a determined flight attendant who raced for an oxygen tank. That he did not die en route to the hospital in Cincinnati was the direct result of an alert pilot’s radio message and a dedicated EMS team.

That he continued to live for 12 years, during which time he taught himself to speak again and became wheelchair ambulatory, was the result of his own refusal to die.

And that he could defy every medical prognosis surrounding his affliction with encephalitis during that period was the direct result of the remarkable self-sacrifice of teammate Jack Twyman, the determination of the best players in the NBA, who set an unequalled standard for caring, and the total commitment of a Catskill hotel owner: Milton Kutsher.

It was Twyman, a Cincinnati resident, who camped out in the hospital, had himself declared Stokes’ official guardian and managed the money while he struggled to find more. And it was Kutsher who set in motion the vehicle that cut into the debts, paid the bills and kept on paying them.

Kutsher gave new meaning to the phrase “Do the right thing” by creating the Maurice Stokes Basketball Game, which drew NBA All-Stars and became a lifesaver for the needy in the basketball community.

It sounds funny now, but back then salaries were more modest, there was no NBA pension plan and a lot of family members of basketball players needed help.

It began when Twyman, desperate for funds to keep Stokes alive, happened to hold a chance conversation with Kutsher. Next to his family, the three things Kutsher loved above all were his fellow man, his Monticello, N.Y., hotel and a competitive basketball game.

“We got a hotel and we got an outdoor basketball court,” he told Twyman. “You tell the players to get here and we’ll house them, we’ll feed them and we’ll sell the tickets.”

Nobody who ever played in the game asked for a plane ticket to get there. Started on an outdoor court, the game ultimately moved into a gym that held 4,000 and sold out every time.

In a world of far too many ersatz heroes, I-got-mine role models and what’s-in-it-for-me superstars, the game was a success thanks to Kutsher and a handful of NBA players with a social conscience.

First it helped Stokes pay his bills, but it lasted well beyond him. Every time others talked about calling it quits, Kutsher reminded them that the game helped Gene Conley, the old Celtic, with his heart problem and his wife with a throat operation. It helped Gus Johnson when he was dying of cancer. It helped Timmy Bassett’s kid, who had a malignant brain tumor. It helped Howard Porter go to drug rehab to turn his life around. It helped John Williamson get dialysis treatments. It helped Mark Jackson’s agent, who was shot on a street corner while walking his dog.

I remember sitting with Knicks’ guard Carl Braun, who would later coach that team, in the hotel lobby on the eve of the game sometime in the 1960s.

“I like Maurice and so I’m here,” he told me. “But after the first time I played in this thing I gave it a lot of thought. Now I’ll play here each year for as long as I can for one simple reason: It could be me in his situation. It could be any of us.”

Over the years, nobody could match Wilt Chamberlain’s quiet devotion. Part of it was his friendship with Kutsher, who once had him as a bellman/player in the good old days. But a lot of it had to do with Chamberlain’s feeling for the men with whom he played the game.

Year after year, no matter where he was, no matter what he was doing, when it came time for the game, Chamberlain, who as a college kid had been a bellhop at Kutsher’s, got there no matter what it took.

In 1970, Chamberlain was rushing back from Europe to play in the Stokes game when he was caught on a connecting flight with a hijacker who took the plane to Denver.

After the plane landed in Chicago and the police took over, Chamberlain chartered a plane. It could take him to Kennedy Airport, but it couldn’t land near Monticello because it was too big. So then he hired another charter to take him from Kennedy Airport to tiny Sullivan County Airport.

Chamberlain was anxious aboard the flight that he’d miss this game. When they finally reached the airspace over the airport, they discovered that the runway lights had all conked out.

“Find me a field and land,” Chamberlain told the pilot. “And call the car rental people.”

You don’t argue with someone 7-feet tall who has biceps bigger than your thighs.

The pilot complied and had a car waiting, but Chamberlain didn’t get to Kutsher’s until the game was ending. He stayed to sign autographs.

“I would do the whole thing over again tomorrow if we had another game like this,” Chamberlain told Kutsher.

Stokes and Kutsher and Chamberlain are gone. But the memory of what they did still shines like a beacon.

I hope Zablocki can save Kutsher’s. I want one day to turn off the New York State Thruway, see the mountain and turn back the clock. And if I do, I know just as sure as God inspired kreplach, a part of me will hear the ghostly thump of the ball against the asphalt and see Milton Kutsher smile again.

(Jerry Izenberg is the columnist emeritus for the Star-Ledger of New Jersey. He was inducted into the National Sportscaster and Sportswriters Hall of Fame and is a winner of the Associated Press’ Red Smith Award for major

contributions to sports journalism — often considered the Pulitzer Prize of sports journalism. This is his 59th year in the business.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.