Rachel and Mayer Abramowitz at a train station in Berlin, 1947.

(Courtesy Abramowitz family)

Filmmaker Gabriel Heim at his apartment in Berlin. (Toby Axelrod)

An unidentified young man standing outside the Duppel DP Camp at Schlachtensee in Berlin, 1946/47.

(Courtesy Ariane Joachim)

BERLIN (JTA) — All its physical traces are gone, but the Jewish DP camp in Schlachtensee is not forgotten.

Sixty-one years since this and the other two such camps here were shut down, a filmmaker has gathered stories of those who passed through on their way from destruction to a new life.

Called “Jewish Transit Berlin: From Hell to Hope,” the 52-minute documentary, which premiered Monday at the Berlin Jewish Museum, relates the unusual and brief history of the Displaced Persons camps set up in postwar Berlin.

Filmmaker Gabriel Heim calls them “the last Jewish shtetls on German soil.”

Born in 1950 in Switzerland to Jewish parents, Heim says he was very lucky to find several people — all now age 80 and above — who were willing to share their memories.

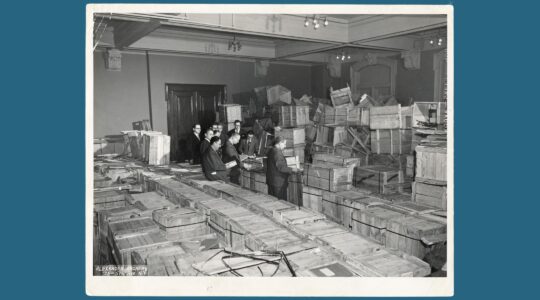

Rich with archival footage and contemporary interviews, the film goes a long way toward painting a picture of their odyssey, which begins with the migration of some 350,000 exhausted Jewish refugees and survivors from Eastern Europe. About 100,000 made their way to bombed-out Berlin, according to Heim. Most landed in other German cities and later emigrated.

“There were thousands of people who were liberated and were displaced in Berlin,” said Rabbi Andreas Nachama, a historian who directs the Topography of Terror archive and heads the Department of Holocaust Studies at Touro College in Berlin. “You had Jews and non-Jews, slave workers and those who were repatriated.”

By January 1946, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee estimated that 6,000 Jews were still homeless in Berlin, where tensions were high between the Soviet Union and other Allies.

“Doors westward closed; please urge solution in Washington,” reads a JDC telegram cited in the film.

The answer was the establishment of three Jewish DP camps: in Tempelhof, Wittenau and Schlachtensee (the Duppel camp), where survivors could safely stay without fear of encountering perpetrators in their midst.

“It was Eisenhower who decided to create DP camps for Jews,” Heim said of Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, then the U.S. Army chief of staff, following clashes in camps shared between survivors and those they recognized as murderers. “The situation was unbearable.”

The separate camps ushered in “a period of hope and of getting into life again,” Heim said.

“It was a magnificent rebirth, a re-creation of people who were so down and came to life,” recalled Rachel Abramowitz, 81, whose father had been deported by Stalin to Siberia from Poland before the war. Afterward, with no one left in Poland, her family made its way to Germany.

They arrived by truck in Berlin in the middle of the night. As children jumped out of the truck, they were met by a U.S. Army chaplain, Rabbi Mayer Abramowitz, who also had arrived in Berlin that day. The rabbi pressed candy into the children’s hands, Rachel Abramowitz recalled in a telephone interview.

“When I jumped out and put out my hand, he said, ‘You are no longer a child.’ ”

Rachel and the rabbi later married, on Nov. 23, 1947, in Berlin. Today they live in Florida and have three children, 11 grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.

Back then Abramowitz — now rabbi emeritus of Temple Menorah in Miami Beach — was a lieutenant with six weeks of chaplaincy training. Given the choice of where to go, he chose Germany, telling his commander, “We heard some Jews survived, and I want to work with survivors.”

Among the things Rabbi Abramowitz did was create a school and summer camp for the 2,300 children in the DP camp.

As in Jewish DP camps across Germany, the refugees had Yiddish newspapers, radio stations and theaters. “Nazis in Hell,” a cabaret revue put on at the Duppel camp, “may be the very first such parody on German soil after the war,” Heim noted.

There were many marriages and many new babies.

Job training “was all organized with a clear view towards immigration to Israel,” Heim said.

David Ben-Gurion, then head of the Jewish Agency, visited Schlachtensee while making his rounds of DP camps in Germany.

With his rabbinic and military credentials, Abramowitz helped members of the Bricha underground acquire the chocolate, cigarettes and coffee they needed to procure gasoline, food and false identity papers at a time when the German mark was worthless and Germans were not allowed to have U.S. dollars.

“It was a mission that probably God blessed me with,” Abramowitz said.

In 1948, with tensions high between the Russians and the Western allies in Berlin, Gen. Lucius Clay ordered the closing of the DP camps in Berlin. By the time the Soviets blockaded the city in June 1948, most of the Jews had left on the same “candy bombers” that had just unloaded emergency food and supplies.

“They were flown out with the airlift,” Nachama said.

Most went on to the United States, Israel, Canada or South Africa, but some 500 remained in Berlin.

Rachel Abramowitz, who taught Hebrew at the camp, went on to become a sculptor and professor of history, Russian and Hebrew at the University of Miami.

“The DP camp was a unique episode of Jewish history,” Rabbi Abramowitz said. “On one hand, you are not at home. You are living in barracks, you line up for food. But on the other hand, it is a beehive of cultural and religious activity.”

Heim hopes his documentary will awaken interest in this chapter of history. The film was co-produced by ARD and Yad Vashem, and co-directed by Ronnie Golz.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.