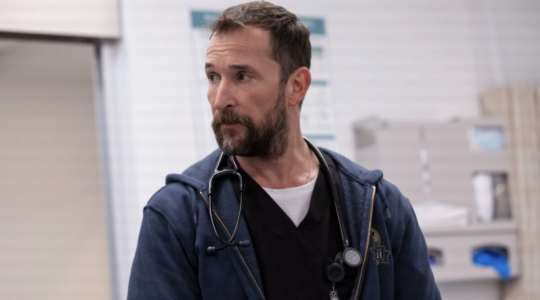

Scene from “Lebanon” illustrates the anguish of war. (Etiel Zion)

TEL AVIV (JTA) — From the depths of an Israeli soldier turned middle-aged filmmaker’s haunted memories, the new award-winning movie “Lebanon” consists mainly of scenes shot from inside a sweat- and anxiety-soaked tank of Israeli army conscripts trapped behind enemy lines.

Accepting the prestigious Venice Film Festival’s top prize last month, Samuel Maoz, the film’s writer and director, said the victory was for all those forever marked by the trauma of war.

“I dedicate this award to the thousands of people all over the world who, like me, come back from war safe and sound,” he said after winning the highest international honor ever bestowed on an Israeli film. “Apparently they are fine, they work, get married, have children. But inside, the memory will remain stabbed in their soul.”

“Lebanon,” which opens this week in Israel, is part of a trilogy of internationally acclaimed Israeli movies on the first Lebanon War to have come out in the past three years.

The films — “Beaufort” (2007) and “Waltz with Bashir” (2008) are the other two — are a reminder that the war’s impact on Israeli society and the men who fought it is still being played out 25 years after the first Israeli tanks rumbled across Israel’s northern border and into a different type of war than Israel had ever known.

Launched in an invasion in the summer of 1982, the war became Israel’s first experience fighting a guerrilla war. What originally was sold to the government by then-Defense Minister Ariel Sharon as a swift operation stretched into 18 years of fighting on Lebanese soil. The Israeli public began to question the war’s goals as it stretched into what was called “the mud of Lebanon” and became known as Israel’s Vietnam.

“Lebanon people began to ask themselves why Israel there, and it became symbolic as the Unnecessary War,” Yehuda Stav, a film critic at Israel’s largest-circulation newspaper, Yediot Achronot, told JTA.

That explains its appeal as a storyline, he said, just as Hollywood’s films about Vietnam continue to capture the popular imagination of U.S. audiences.

In films depicting Israel’s earlier wars, there was little hint of the self-doubt and critique of Israeli society that began to emerge after the first Palestinian intifada in the late 1980s, Stav said. Movies at the time started to express an Israeli sentiment that came to be known derisively as “shooting and crying” (in Hebrew, “yorim v’bochim”) — a label bestowed by anti-war Israelis on left-wingers who took part in what they viewed as questionable military missions only to return and criticize the army and the government for what they themselves had participated in.

The current wave of Lebanon movies in some ways continues the trend, Stav said, in particular “Lebanon” and “Waltz with Bashir.” Both wrestle with individual soldiers’ internalized, suppressed emotions reflecting traumatic events the filmmakers themselves experienced fighting in Lebanon.

A common denominator in the films is their viewpoint limited to one slice of the war: the experiences of individual characters. In the case of “Beaufort,” it’s the characters at the Crusader-era fortress of the same name on the eve of Israel’s withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000. The audience sees no more than the characters do from their hilltop perch.

“Waltz with Bashir,” an animated documentary that made the Academy Awards finals in the Best Foreign Film category last year — “Beaufort” had reached that milestone the previous year — explores what the Israeli role may have been during the massacre of Palestinians at Lebanon’s Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in a narrative drawn from the repressed memories of filmmaker Ari Folman and his fellow soldiers.

In “Lebanon,” the war is viewed from the perspective of four soldiers manning a tank that has been dispatched to search a hostile town only to become lost amid Syrian forces. The film shows little more than what the soldiers themselves see: a limited line of vision to fighting outside the tank and the dynamic of terror inside the tank, as four young men try to navigate their vehicle — not just a machine of war but a potential death trap — back to safety.

Yvonne Kozlovsky-Golan, an academic who researches the theme of war and film and teaches at Sapir College in southern Israel, says it’s not surprising that it has taken awhile for films to be made about the war.

“Post-trauma usually takes about 10 years to come out, not only in film but literature too,” she said.

Lebanon War-related films are coming out now because of financial reasons, too. In recent years, as Israel’s film industry has grown and received more recognition, Israeli productions have drawn greater investment from abroad. Even though all three films were made on relatively limited budgets, they had the support of European co-producers.

Some have described the films as anti-war treatises and one of the reasons liberal European funders — and audiences — found them palpable.

But Kozlovsky-Golan sees them differently.

“It may be fashionable to call them anti-war movies, but in the very origins of these films is a theme of the Jewish value of being a pursuer of peace, a ‘rodef shalom,’ ” she said.

“In the Talmud, a debate emerged that concluded that Jews should refrain from confrontation and not be involved in war-like situations,” Kozlovsky-Golan said. “And even though these filmmakers are secular Jewish Israelis, I see that this tradition is also rooted in them, this feeling that somehow war is not a Jewish thing.”

Meir Schnitzer, a film critic for Israel’s daily Ma’ariv, said the films promote the image Israelis would like to see of themselves.

“The films are a continuation of the feeling that Israel is the victim in the Middle East conflict,” he said. “They act as a salve against charges that we are war criminals.”

David Silber, the producer of “Beaufort” and “Lebanon,” said the films on the Lebanon War serve a social function.

“They help people understand the misery of war, the need to explain again and again that it’s a terrible thing and should only be chosen as a last resort,” Silber said. “I don’t know if we are still paying a price specifically for the Lebanon War, but the far bigger issue is that we have been at war for the past 100 years here.

“On one level we are a post-traumatic society,” he said, “and these films give expression to that.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.