Does the return of Cold War rhetoric between the United States and Russia and an ongoing rollback of democratic rights in Russia mean that the Jewish community of Russia is facing the scepter of a return to the bad old days of the Soviet Union?According to an assortment of Russian Jewish leaders spanning the religious and ideological gamut from the Chabad Lubavitch-affiliated chief rabbi of Russia, Berel Lazar, to leaders of more secular bodies like the Russian Jewish Congress, the answer is an emphatic “No.” Russia is not, they say, again becoming an uncomfortable and dangerous place for Jewish to live and work.

All of the leaders stressed that Russian Jews today enjoy the right to open and operate as many synagogues, Jewish schools and organizations as they like, to participate fully in the life of the country and to emigrate from it. They credit the Putin government with moving quickly in recent years to crack down on individuals and groups that target Jews for defamation and violent attacks. The Russian Jewish leaders seem inclined to believe that a series of eye-raising remarks by Russian President Vladmir Putin in recent weeks — he accused the United States of pursuing a “unilateralist” foreign policy bent on imposing its “hegemony” on the rest of the world, and on one occasion compared the U.S. to the Third Reich — were mainly attention-getting rhetoric by the Russian president and of little significance.Putin’s purpose, they say, was to give expression to strong feelings among Russians that by expanding NATO into the heart of the former Soviet bloc and by building an anti-missile system in the Czech Republic and Poland allegedly targeted against Iran, the U.S. has not treated Russia with respect.

Yet on the issue of the erosion of democracy in Russia, the Jewish leaders offered more nuanced positions; they argued that while Jews thrive best in a democratic milieu, democracy is not per se a Jewish issue as long as the community is in a position to weigh in with the authorities on issues like anti-Semitism and xenophobia.

In a telephone interview, Rabbi Lazar told The Jewish Week he was elated by a promise Putin made to him during a meeting at the president’s home last week to contribute one month’s salary to the construction of a Russian Jewish Museum of Tolerance. It was “a strong signal of President Putin’s commitment to fight against anti-Semitism and xenophobia,” he said. “People were struck by the fact that this is the first time the president ever offered to donate his salary to any cause.” Rabbi Lazar, who was named chief rabbi by Putin in 2000 and who meets one-on-one with the Russian president three or four times a year, said he is not overly concerned by what he termed “extreme rhetoric” used by Putin against the U.S. in recent weeks. He argued that Putin’s shrill speeches should be seen in the context of U.S. policies which, the rabbi said, “failed to pay enough attention to Russian pride.”The rabbi expressed relief at the apparently lowered tension level between Bush and Putin after the recent G8 meeting. At the meeting, Putin put forward a proposal for the two countries to build a joint anti-missile system in Azerbaijan to protect Russia and Europe against a potential missile attack from Iran. According to Rabbi Lazar, “The Jewish community’s interest is for Russia to be in understanding with the Western world and with Israel.” Asked whether American Jews should be alarmed about potential dangers for their brethren in Russia at a time when opposition demonstrations are routinely broken up, and the media is ever more tightly controlled by the Kremlin, Rabbi Lazar responded, “Not at all.

“American Jewry,” he continued, “fought for decades for the right of Russian Jews to be free, and that day has arrived. There has been a great Jewish revival in this country, and President Putin and his government are sincere about giving Jews full freedom.”

Asked whether democracy is necessary for healthy Jewish life, Rabbi Lazar responded, “Democracy has no relevance to the work of the organized Jewish community, although it certainly matters for individual Jews. There is a debate on these issues in the Jewish community. Some on the liberal side of the community are unhappy [with the government], but others feel that the present state is much better for the community than the situation in the 1990s.

“Today, there is less corruption, and fewer killings. When acts of anti-Semitism occurred in those days, people were rarely brought to trial, which is no longer the case today.”

Nevertheless, Rabbi Lazar believes the best course for Russia would be “a middle way, a golden path between too much freedom and too much control.” Asked whether he raised the issue with Putin at their recent meeting, the rabbi responded, “I spoke mainly with him about world politics and Israel, but these issues came up, too. He knows how we feel.” Nikolai Propirny, executive director of Russian Jewish Congress, a mainly secular umbrella body that is the second most prominent Jewish organization in Russia after the Chabad-linked Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia (FEOR), said he was unconcerned about the police breaking up recent political demonstrations in Moscow by opposition groups headed by self-described liberal democrats like former chess champion Gary Kasparov and one-time Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov.According to Propirny, “The reason that the opposition is weak is because it lacks strong leaders, not because of government repression. In any case, why should we take part in demonstrations and get in a fight with the government? We have our own Jewish issues to deal with.”

Yevgeny Satanovsky, the outspoken former president of the Russian Jewish Congress who is today president of the Institute for Israel and Middle East Studies, a Moscow-based think tank, is forthright in endorsing Putin’s crackdown on democracy.

“A centralized system of power is good. Otherwise, we would likely have an independent Tatarstan and an independent Siberia, and perhaps an independent Moscow fighting independent St. Petersburg.”Satanovsky said, “Whatever else one might say about Putin, he is philo-Semitic and pro-Israel. Maybe Putin’s successor will be less friendly than he is, but the main thing is that to be anti-Israel or anti-Semitic is no longer part of acceptable political culture in Russia.” Satanovsky predicted, “Despite the present problems, relations between Russia and the U.S. will recover. I believe Russian Jews, who have interests in Russia, the U.S., Israel and Europe, will play a bridging role in all of this. There are Jewish businessmen like [Leonard] Blavatnik, [Mikhail] Fridman and [Viktor] Vexelberg doing enormous business together in both Russia and the West. Blavatnik is a U.S. citizen and the other two are Russian citizens, but collectively they work as a bridge between the two countries.”

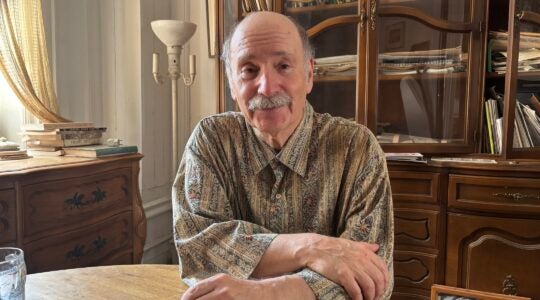

Mikhail Chlenov, 66, the Moscow-based general-secretary of the Euro-Asian Jewish Congress (EAJC), an umbrella body encompassing the Jewish communities of the FSU and other East European and Asian countries, as well as president of the Va’ad of Russia, is a liberal secularist whose pedigree in the Jewish and human rights movements in Russia extend back to the 1970s.

Yet Chlenov believes American Jews have an overly bleak impression of what is happening in Russia. “In fact, there is no state-sponsored anti-Semitism today, as existed in Soviet times,” Chlenov said. “We are able to raise forcefully with the government issues of Jewish concern, including anti-Semitism and xenophobia.” On the issue of democracy, Chlenov observed, “The paradox of today’s Russia is that we see limitations on certain liberties going hand in hand with a growth in living standards.” He noted that Jews are less prominent in groups defending human rights and civil liberties than in the past, pointing both to unhappiness with the leadership of the democratic movement and what he acknowledged is “increased fear by many people to criticize the authorities.” In any case, he said, “These are not issues of specific Jewish interest and we have never urged Jews as a movement to become involved in the political struggle.”Mark Levin, executive vice president of the Washington-based NCSJ, said he heard similar defenses of Putin and his policies from unnamed Russian Jewish leaders during a visit to Moscow last month.Nevertheless, Levin noted, many of the same leaders were not displeased that he and other members of the NCSJ delegation raised concerns about the erosion of democracy during meetings with high Russian government officials. “The Jewish leaders said to us, ‘You can raise issues that we can’t,’” Levin said, adding, “While we may not agree with our Russian Jewish counterparts on every point, a strong partnership continues to exist betwee

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.