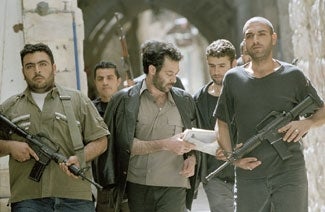

LOS ANGELES, Jan. 22 (JTA) — Early in the morning of Jan. 31 here, some sleepy official will read off the nominations for the 78th Academy Awards, and perhaps none will follow the announcements more anxiously than filmmakers in 58 foreign countries. The Israeli entry, which highlights the plight of foreign workers in the Jewish state, is unlikely to be nominated, but the German, Hungarian, and Palestinian entries offer storylines that should be of special interest to Jewish viewers. Judging by critical buzz and personal reviews, here are the films’ nomination chances, ranked from best to worst. “Paradise Now,” which follows two suicide bombers from Nablus in their painstaking preparations to blow up a Tel Aviv bus, reenforced its frontrunner status earlier this month when it picked up the Golden Globe award for best foreign film. Although the sympathies of director Hany Abu-Assad lie clearly on the Palestinian side, he avoids a simplistic tirade. With excellent acting and a tight, tense plot, the film tries to give an insight into the motivations of the terrorists, their sense of humiliation under Israeli occupation, their fanaticism as well as their doubts and misgivings. In what may be a nod to Western sensibilities, a beautiful Arab woman, who tries to dissuade the bombers from their mission, is given a central role. For shrewd political or artistic reasons, the film concludes without exposing viewers to the ultimate horror and carnage of the bombers’ goal. “Sophie Scholl: The Final Days,” Germany’s official entry, is the most recent attempt by the country’s young filmmakers to wrestle with the dark legacy of the Hitler era. The movie is a tribute to the death-defying courage of a small group of German university students, who posted anti-Nazi leaflets throughout Munich and Germany at the height of World War II. Sophie Scholl, a 21-year-old Protestant, was the only woman at the core of the underground resistance group known as the White Rose. Despite her discovery and execution, the film’s message and portrayal of her is hopeful and defiant. Hungary’s entry, “Fateless,” one of the most nuanced Holocaust films ever made, has won high critical acclaim but is probably too ambiguous to win Oscar recognition. The story is based on a novel by Hungarian Jewish writer Imre Kertesz, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2002, and it is told through the eyes of 14-year-old Gyuri Koves. Koves, hauntingly portrayed by Marcell Nagy, is randomly taken off a bus, sent to Auschwitz and other camps, and survives and returns to Budapest. While not shrinking from the horror of the concentration camps, “Fateless” is told through a boy’s very personal perspective and often has an almost dreamlike quality. To many viewers, the most shocking aspect may be Gyuri’s voice-over musings as he wanders the streets of Budapest after liberation. “There is nothing too unimaginable to endure,” he thinks, and when asked to relate the atrocities he has endured, opts to speak of his happiness. “The next time I am asked, I ought to speak about that, the happiness of the concentration camp. If, indeed I am asked. And provided I myself don’t forget.” What is that happiness? Director Lajos Koltai, in a phone call from Budapest, tried to explain. “The boy remembers the happiness of once in a while finding a small piece of meat or potato in his thin soup, or the friendship of older prisoners who saved his life. And mostly, he remembers the happiness of the short hour between the end of backbreaking work and supper, when he could watch the sunset and quietly talk to the others.” Kertesz, who also wrote the screenplay, gave a more subtle explanation in a New York Times interview. “I took the word happiness out of its everyday context and make it seem scandalous,” he said. “It was an act of rebellion against the role of victim which society had assigned to me. It was a way of assuring my responsibility, of defining my own fate.” In the ironically titled “What a Wonderful Place,” the focus is on the mistreatment of foreign workers, which is a real-enough Israeli problem. But what we get from director Eyal Halfon is a lineup of Israelis who pimp and rape imported Russian prostitutes, beat their foreign farm workers, cheat on their spouses, humiliate their children, and commit suicide. Oddly enough, the Israeli film industry submits “Wonderful Place” and similar downers even while the overall level of Israeli movies (“Walk on Water” and “Yossi & Jagger” spring to mind) has steadily improved. And, ironically, the similarly improved Palestinian movies, while wasting no love on the occupation, manage to present most Israelis as recognizable human beings. One can surely admire Israeli filmmakers for unsparingly criticizing their society’s shortcomings. Similarly, the disinclination of Israelis to celebrate their military triumphs on film, even after the 1967 victory, is admirable. But somebody needs to tell the Israeli Academy that judges on the Oscar selection committees, particularly Jewish ones, may resent heavy-handed portrayals of all Israeli Jews as cheats, brutalizers, and all-around lowlives. Little wonder that the last Israeli film to be Oscar nominated was back in 1984 and that none has ever walked off with the golden statuette. Also of interest is Chile’s entry, “Play,” directed by young Jewish filmmaker Alicia Scherson. It is described as presenting “the social fabric of the capital city, Santiago, through a collision of oddball characters.”

Help ensure Jewish news remains accessible to all. Your donation to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency powers the trusted journalism that has connected Jewish communities worldwide for more than 100 years. With your help, JTA can continue to deliver vital news and insights. Donate today.