The June morning is perfumed with freshly mown grass in front of Cape Cod homes near the Queens-Nassau line. The lawns are dark green from being watered, and the sidewalks are dark from the water, too. The streets are wide, quiet. The sun beats down on the borderline of summer. The rebbe of Lubavitch sleeps in the Old Montefiore Cemetery that begins where the backyards end. It doesnít much look like a chasidic holy site, but neither does the Congo, Marrakech, Katmandu, Mexico, Connecticut or Shanghai, and there are Lubavitchers now in all of them. Because of the rebbe who sleeps in Queens there are more than 2,500 sites, in more than 50 countries, on every continent, where his picture hangs and God is praised.

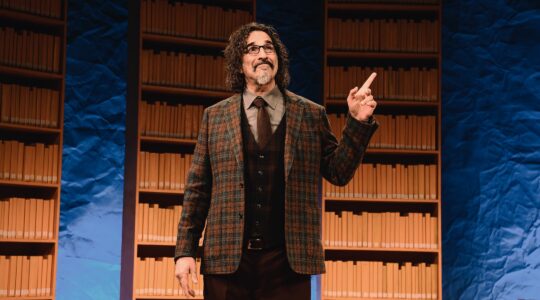

Five years ago this week, Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson died on the Hebrew date of Gimmel Tammuz (June 17). Non-chasidic speculators offered immediate expertise: messianism would break the movement in two; Lubavitch would go crazy, disintegrate, without a rebbe; theyíd suffer from mass depression, and violent battles over succession. Experts predict this still. Of course, no expert predicted what actually happened: Chabad Lubavitch has grown exponentially, perhaps more than any other Jewish group in the last five years. Other than messianic pockets in Crown Heights and Kfar Chabad, Lubavitchís center in Israel, where there is a strong belief that the rebbe is still the Redeemer, the predicted divisions havenít affected the international mission.The numbers are remarkably eloquent: According to Zalman Shmotkin, director of the international Lubavitch News Service, since Gimmel Tammuz, and ìinspired by the rebbe,î 511 new institutions were founded, 108 in 1999 alone, bringing the planetary total to 2,523. Since 1994, 393 Chabad couples have gone out as the rebbeís emissaries, bringing the total to 3,900 emissary families. More than 800,000 children attend Chabad-Lubavitch day schools, afternoon schools and summer camps around the world.Of course, after World War II, Chabad Lubavitch started this empire out of nothing more than one solitary shul on Eastern Parkway. Oh, one more thing: They had a rabbi with a vision.But critics keep carping. A recent article in the Jerusalem Report says the movement ìmay be in the midst of a slow-motion schism,î though Chabadís numbers are warp-speed positive. Well, says the Jerusalem Report, ìChabadniks normally refer to [the rebbeís passing] as ëGimmel Tammuz,í the third day of Tammuz, to avoid saying what happened on that date.î It is an oft-repeated critique, proof that Chabad hasnít come to grips.In fact, every Jewish date of sorrowful origin is referred to only by its date. For example, Mosesí death date has no other name but Zayin Adar, the seventh of Adar. Would anyone say that Jews havenít come to grips with the death of Moses? The anniversary of the Templeís destruction is called nothing but Tisha BíAv. So it is with Gimmel Tammuz.As Chabadís Rabbi Manis Friedman says, chasidim may have blind faith but not unbridled faith. They are bridled, brilliantly resilient. While the experts warned of messianic paralysis on that sad Gimmel Tammuz, the chasidim went to work: a carpenter chasid sawed wood from the rebbeís lectern to build a casket. A chasidic Chevra Kaddisha gently poured water over the rebbeís body, and wrapped him in a shroud. Gravedigging chasidim drove early to Old Montefiore Cemetery to dig their rebbeís grave. Straw was placed on the floor of the rebbeís room at 770 Eastern Parkway, and the rebbeís body was lowered to the straw. Then they drove to Old Montefiore and laid him in the ground. They did what they had to do.Rabbi Friedman, whose son had his aufruf in the minyan that continues to pray in the rebbeís room at 770, lives in Minnesota but comes to the Ohel six times a year.ìAmong chasidim, the yahrtzeit of a tzadik [holy man] is celebrated, not mourned. Of course, the first few years are sad, but then it grows into a very auspicious day. The [departed soul] rises to a higher level and takes everybody with him. Weíll be having Sheva Brachos for my son on Gimmel Tammuz; a couple of years ago we wouldnít have done that.îThe night the rebbe was buried, some young chasidim in their 20s stayed, sort of an honor guard. One of the chasids was Abba Refson, then 22. No one told him to stay, ìit was spontaneous,î Refson says. ìEventually, the others took their own path, but I felt I wanted to be here.îOther than brief excursions, Refson stayed on through that first summer and autumn, through moonless nights when winter winds blew through the gravestones. After a while, he stayed in a modest mobile home parked inside the cemetery gates. He kept Psalms on hand, candles, and copies of Maaneh Lashon, an old book of graveside meditations.In time, Australian philanthropist Joseph Gutnick, a chasid, purchased one of the small homes at the cemeteryís edge, and Refson moved indoors.

In one room, a video plays tapes of the rebbe. Other rooms were converted into a shul and library, a place to compose oneís thoughts and write the notes that traditionally are written at holy graves, or holy ruins like Jerusalemís Wall. The Ohelís kitchen is well stocked with coffee, water, cookies, peanuts and fruit; each of which is provided not only to refresh but also to give the visitor a chance to say as many blessings as possible.Four other small homes have been purchased on the block. Theyíre used as a dorm for distant visitors, a home for Refson, a cheder for children bussed in from Crown Heights, and a menís mikveh for a purifying immersion before visiting the Ohel (a word meaning ìtent,î as the chasidim call the square, stone, open-ceilinged enclosure around the rebbeís grave, and the previous rebbeís grave).Three fax machines are whirring in a closet, leaving more than 600 daily notes and requests for blessings. Refson, of a remarkably sweet and gentle demeanor, apologizes for interrupting his conversation to pick up the phone. ìIt might be an emergency,î he explains.At the grave, a group of 12 visitors from Argentina are reciting Psalms: ìMizmor Shir LíHashem, Shir Chadash … Salmo canten al Eterno un cantico nuevo.îLeonardo Nomesky says, they were all born and raised outside Orthodoxy, and they look anything but Orthodox now. But theyíve grown close to Chabad over the years: ìWe came here, our group, to find spirituality. Weíve listened to and studied the rebbe, studied Torah and mitzvot, and Tanya, in our Chabad in Buenos Aires.îOh, theyíll go to the Empire State Building, too, but coming to New York means going to the rebbe. Itís become an internationally famous spiritual destination, similar to Mother Rachelís grave near Bethlehem.Also arriving is Israeli Lieut. Col. Eli Barda, Migdal HaEmekís newly elected mayor on the Sephardi Gesher ticket. ìI am not a chasid but believed in the rebbe; when I came to New York I decided to visit here.î Wearing an open-collared blue shirt, the mayor adds, ìThe fact that I am here says everything better than I can say.îBible students know of the story in the Book of Joshua about the sun that didnít set. Ancient tradition says that happened on Gimmel Tammuz. The sun hasnít set yet.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.