The injection of religion into the American presidential campaign has elicited sharp criticism from Jewish Democrats, some concern from Jewish organizations and approval from some Jewish Republicans.

“For George Bush to criticize the Democratic platform for not mentioning the word ‘God’ is unseemly and has no place in American politics,” the National Jewish Democratic Council, a pro-Democratic party group, said in a statement Monday.

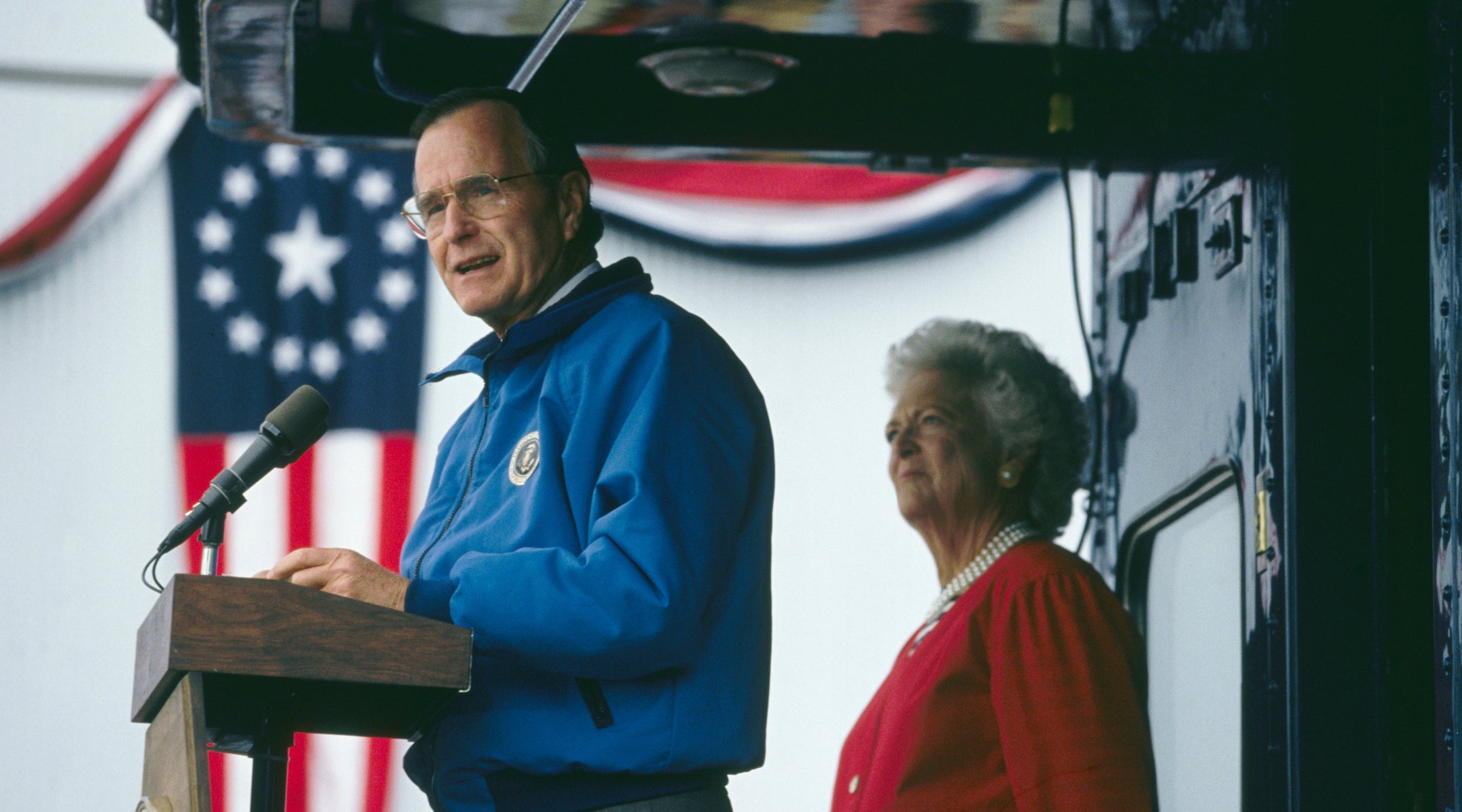

Speaking before a convention of evangelical Christian leaders last weekend, President Bush had said he was struck that “the other party took words to put together their platform but left out three simple letters: G, O, D.”

The Jewish Democrats charged that “Bush’s willingness to manipulate religion for political gain is an accurate reflection of the Republican Party’s pandering to far-right activists. It is inexcusable that a supposedly mainstream political party in this country is so adverse to tolerance and pluralism.”

The reaction was more muted, however, from Jewish organizational officials.

While most predicted that the Republican appeals to their most conservative and evangelical constituents would cost them Jewish votes, few wanted to judge the propriety of the campaign.

Their reluctance may have been motivated in part by a federal regulation prohibiting tax-exempt groups from engaging in partisan political activities.

‘HARMFUL TO OUR POLITICAL SYSTEM’

But Jewish groups in the past have taken strong stands on limiting the role of religion and religious groups in the political process.

In 1985, the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council adopted a policy statement calling on public officials, candidates for public office and political parties “to reject categorically the pernicious notion that only one brand of politics or religion meets with God’s approval and that others are necessarily evil.”

Lawrence Rubin, the umbrella group’s executive vice chair, said he thinks the Republicans have gone “over the line.”

“When people start using religion as a club in the political process, that’s harmful to our political system,” he said. “It creates a sense of those who are in and those who are not. It raises a question of the entanglement of church and state.”

Similarly, Phil Baum, associate executive director of the American Jewish Congress, said that religious belief and commitment “should not be a matter for partisan politics.”

“Religion is demeaned by using it in a partisan political manner,” he said.

“I think many Jews are deeply uncomfortable when they see this heavy mix of religion and politics, and sense that the two are too heavily intertwined,” said David Harris, executive vice president of the American Jewish Committee.

“It’s going to make the Republican quest for Jewish votes in November much more difficult,” he said.

Rabbi Alexander Schindler, president of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, agreed that the injection of religion into the campaign is nothing new and said it would likely hurt the Republican quest for Jewish votes.

What it would not hurt, he said, is the country itself.

“I don’t think this rhetoric will change attitudes,” said the Reform leader, referring as well to other statements at the Republican National Convention last week that were criticized for appealing to various forms of prejudice.

“It just tries to get support from people who are already prejudiced,” he said.

‘JUST A QUADRENNIAL RITE’

And Abraham Foxman, national director of the Anti-Defamation League, said that the rhetoric at the Republican convention should not be a serious matter of concern.

“The Jewish community is more sophisticated,” he said. “We realize to what extent this is just a quadrennial rite, whose purpose is first to serve the inner needs of the party faithful and then to play outward.”

“I don’t think the Jewish community, as a Jewish community, fared well at either of the conventions,” he added.

“Israel, anti-Semitism — they weren’t mentioned at the Democratic convention; ironically, the only one who spoke on those terms was Jesse Jackson. The Republican convention had a similar element, where Pat Buchanan spoke on Judeo-Christian values.

“Sure, the Jewish community would have preferred that Buchanan not be highlighted at the convention, but I’m realistic enough to understand that to the party it was a necessity,” he said.

“I’m realistic enough to know that the phrase ‘Judeo-Christian values’ does not flow as a matter of course from Mr. Buchanan, that it was a matter of course from Mr. Buchanan, that it was a matter of sensitivity, he tried to be responsive.”

In his speech before the convention, Buchanan characterized the campaign as part of a “religious war going on in our country for the soul of American.”

He attacked the Democrats’ support for abortion rights and gay rights, as well as their opposition to public funding for private and parochial schools, by calling it a deviation from the “Judeo-Christian values upon which this nation was built.”

“It is not the kind of change we can abide in a nation we still call God’s country,” he said.

MANY JEWS FEELING ESTRANGED

Foxman said that the convention left many Jews feeling estranged and seemed a reversal of more than a decade of Republican outreach to the Jews. But he predicted this would be offset by the actual tone the campaign will take locally in New York, Chicago and other cities with large Jewish populations.

But Matthew Brooks, executive director of the National Jewish Coalition, a Republican group, doesn’t see what all the fuss is about. He dismissed Buchanan’s convention role as being a “lone voice with a narrow constituency.”

Brooks said Jews should not be offended by bringing God into the political arena.

“What is wrong is the assumption in the Jewish community that when someone mentions God, they’re trying to make it a Christian God,” he said.

“Do I think it’s bad that George Bush mentioned God? Absolutely not.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.

The Archive of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency includes articles published from 1923 to 2008. Archive stories reflect the journalistic standards and practices of the time they were published.