Philip Roth’s latest biographer wants Jews to read him again — without the guilt

It was a scandal right out of a Philip Roth novel: Days after the publication in 2021 of his long-awaited biography of Roth, author Blake Bailey was credibly accused of sexual misconduct. The publisher pulled the book, pulping all the copies.

Even before the uproar, many younger readers lumped Roth among the “great white males” of mid-20th-century literature, and throughout his career Roth was dogged by accusations that he was a misogynist, both in his fiction and his private life. The scandal seemed to confirm these accusations by proxy, conflating the author and his biographer.

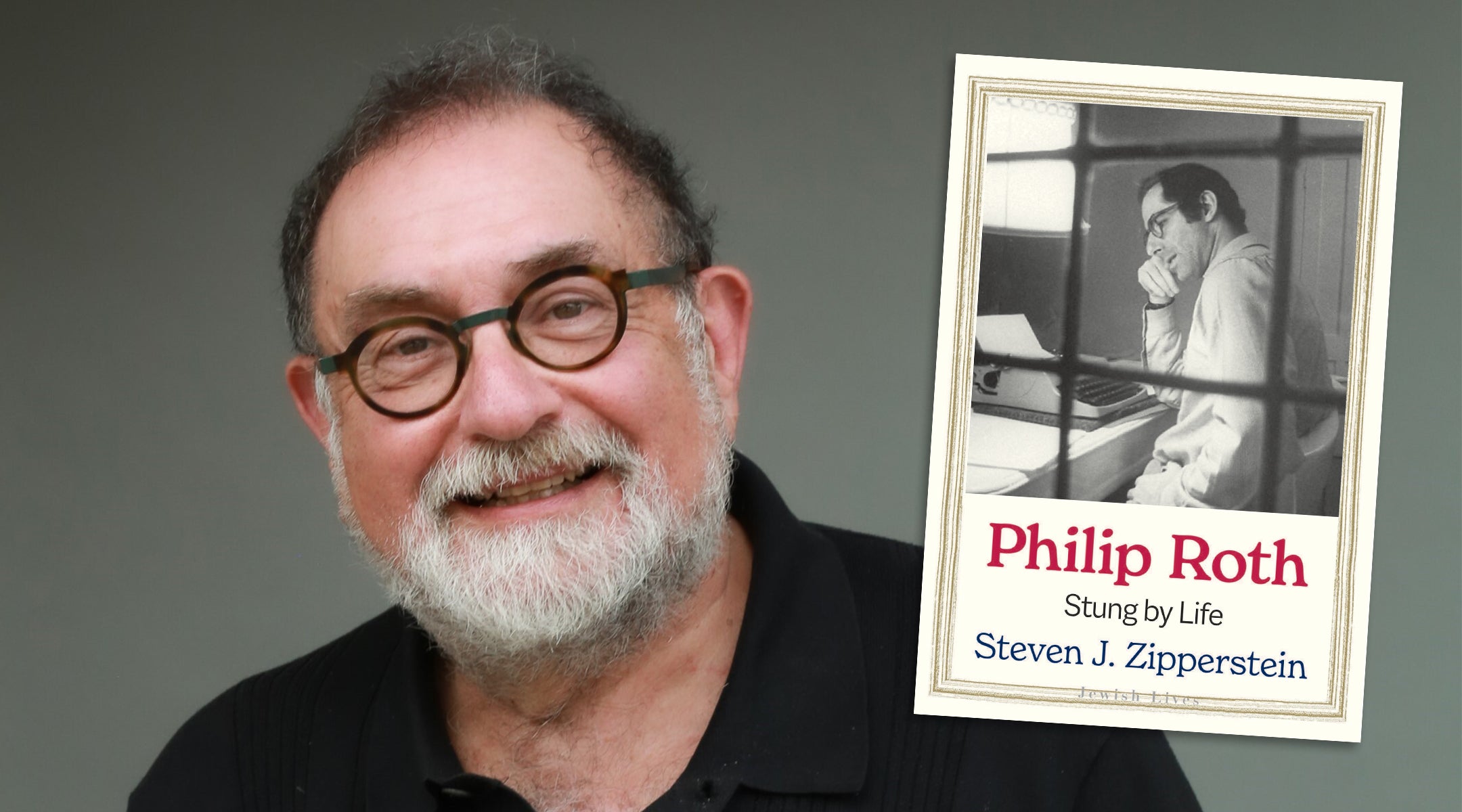

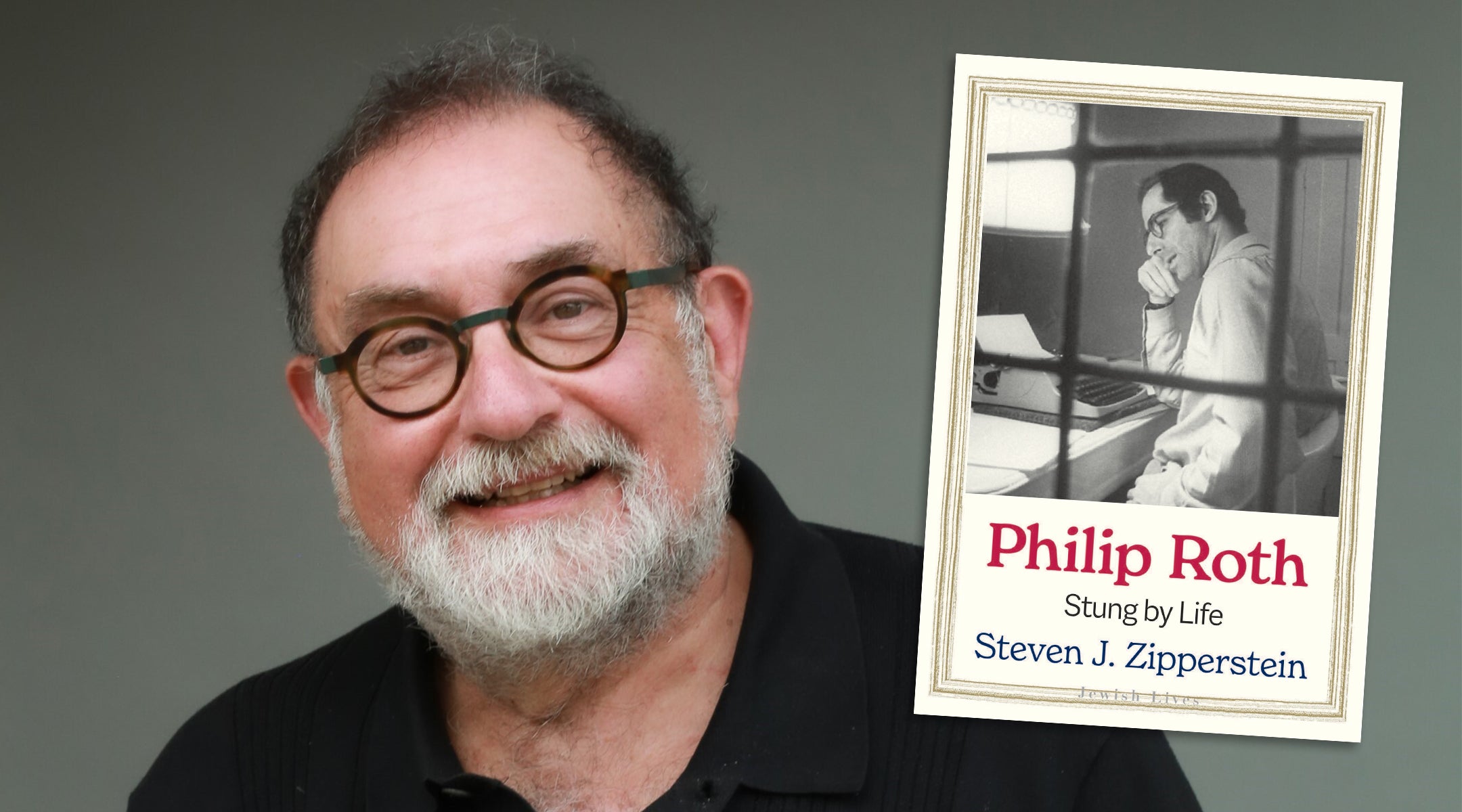

Stanford historian Steven J. Zipperstein had already begun his own biography of Roth before the author died in 2018 and while Bailey’s book was under contract. “Philip Roth: Stung by Life,” part of Yale University Press’s “Jewish Lives” series, isn’t meant as a corrective to Bailey’s book or the fallout. But it does argue why Roth remains relevant and vital, especially to current Jewish discourse.

Writes Zipperstein: “He would probe nearly every aspect of contemporary Jewish life: the passions of Jewish childhood, the pleasures and anguish of postwar Jewish suburbia, Israel, diaspora, the Holocaust, circumcision, the interplay between the nice Jewish boy and the turbulent one deep inside.”

Zipperstein is the Daniel E. Koshland Professor in Jewish Culture and History at Stanford University, whose previous books include “Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History.” He first met Roth when he invited the author to speak to his colleagues and graduate students at Stanford. Roth showed up with a blonde woman in a silky blouse — not his wife at the time, actress Claire Bloom — and proceeded to spend the session flirting with her. His students were not amused.

They met again over the years under less antic circumstances and Roth gave his blessing to Zipperstein’s project. “We carried on a series of conversations, and he introduced me to his loyal entourage, and made it clear to them that they could share things with me that they otherwise might not have shared,” Zipperstein told me.

In our conversation, held over Zoom this week, Zipperstein and I spoke about how Roth scandalized the Jewish world with early works like “Goodbye, Columbus” and “Portnoy’s Complaint,” how he both resented and cherished his Jewish readers, and why so much of his prodigious output still holds up.

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

How did you come to write a biography of Philip Roth? He already had an authorized biographer, so what did you hope to bring to your book?

I’d met Roth years ago at Stanford — there’s a brief mention of it in the book. After I finished “Pogrom” there was this long pause before it came out [in 2018], and I started wondering what I might do next. I’d helped found the “Jewish Lives” series, and Roth seemed a pretty good fit.

But honestly, he’d been in my head long before that. I first read him in Partisan Review — a chapter from “Portnoy’s Complaint” called “Whacking Off” — just before I went off to the Chicago yeshiva. I was raised in an Orthodox family, wrestling with whether I could stay in that world. And Roth’s voice — it stuck with me. Not because of the masturbation, but because Portnoy has all this freedom and he’s miserable. That hit home. It told me that leaving the world I was raised in wasn’t going to be simple, and that freedom wouldn’t necessarily make me happy. That realization — about freedom and its discontents — has stayed with me my whole life as a historian.

Then, years later, I came across the recording of the Yeshiva University event in 1962 — the one Roth described as a kind of Spinoza-like excommunication. The tape told a completely different story. That was the moment I thought: there’s a book here, about the distance between Roth’s memory and reality.

Steven J. Zipperstein said his training as a historian helped him separate truth from fiction in writing his biography of Roth. (Yale University Press)

Let’s talk about that Yeshiva University event. Roth at the time was the young author of “Goodbye, Columbus,” which includes stories that some rabbis and others in the Jewish community said portrayed Jews in a negative light. Roth was invited to sit on a panel with Ralph Ellison and an Italian-American author to talk about “minority writers,” and Roth would later insist that the audience “hated” him. What did you find when you listened to the recording?

Well, Roth remembered it as this traumatic scene — the audience attacking him, shouting him down. But on the tape, the audience loves him! They’re laughing, applauding. The only confrontation comes from a few guys who come up to the stage afterward to argue.

What interested me wasn’t just that Roth misremembered it — it’s how he misremembered it. It tells you something about how he experienced the world. The people who criticize him are the ones who loom largest. That was revealing to me, both as a biographer and as someone who’s taught for decades. The people who dislike you — they’re the ones you remember.

But there is an almost literary bookend to that event: In 2014, the Jewish Theological Seminary awarded Roth an honorary doctorate. How did he react to that?

He was stunned! It was a casual decision by the institution, but a momentous decision as Philip saw it. He said in his speech, “This is the first time I’ve been applauded by Jews since my bar mitzvah.” He meant it sincerely.

Roth wasn’t a historian; he was a novelist. He remembered as he felt, not as it happened. My job was to separate those two things, not to punish him for it, but to understand the gap.

Roth once said, “The epithet ‘American Jewish writer’ has no meaning for me. If I’m not an American, I’m nothing.” As someone who insisted that he was first and foremost an American writer, as opposed to a Jewish writer, would he have liked being part of the *Jewish Lives” series?

Oh, I think so. He thought it was fair. We never talked about it directly, but I suspect he would’ve liked the company — King David, Solomon, Freud, Einstein.

There’s this anxiety about calling writers like Roth or [Saul] Bellow or [Bernard] Malamud “Jewish writers,” as though that makes them smaller. No one says Chekhov isn’t Russian enough. But say “Jewish writer” and people start to hedge.

I once said an American Jewish writer is someone who insists he’s not an American Jewish writer. Roth fit that perfectly.

There was a time when the Jewish experience was seen as a lens through which to understand modern life. Jews were central, not peripheral. Roth captured that paradox: Jews as both insiders and outsiders, too white and not white enough, privileged yet insecure. That ambivalence is his great theme.

“Portnoy’s Complaint” came out in 1969 and both delighted and scandalized readers with its descriptions of the narrator’s sexual adventures and fraught relationship with his Jewish parents. The reaction was extraordinary. I think it may be hard in our current era to imagine a literary novel selling so many copies and becoming such a part of the pop culture landscape.

[Critic] Adam Kirsch said it best — it was one of the last times a novel could set off the kind of cultural frenzy that today only Taylor Swift can provoke. The timing was perfect: Censorship had loosened, the sexual revolution was on, and “Portnoy” hit a nerve.

Roth claimed afterward that he didn’t want that kind of fame again. But of course he missed it. He hoped “Sabbath’s Theater” [his 1995 novel] would do it again. He knew it wouldn’t. He was mourning the loss of a serious readership, even as he kept writing as if it still existed.

Roth’s reputation seems tied up in how he portrayed women in his fiction and how he treated women in his personal life. You describe his serial relationships with many, many women, which often ended as soon as the sexual excitement wore off. At the same time, many of these same women remained loyal, and many gathered at his bedside as he lay dying, and some have written admiring memoirs. How did you approach that paradox?

I tried to be honest without being prurient. Roth decided very early that he was going to be a great writer — perhaps as great as Herman Melville or Kafka — and he came to conclude that there’s not a whole lot of discretionary time for relationships.

He’d fall in love hard, live with someone for two or three years, then move on. I didn’t moralize about it. Many of those women remained close to him. Others didn’t. He was loyal in his own way.

And his relationships with men, except for one significant detail, are not vastly dissimilar from those that he has with women. They’re utilitarian. Incredibly loyal friends hang on, because they’re so enamored by Roth and they feel deeply protective of Roth.

He also listened more intently than anyone I’ve ever met — though you were never sure whether it was you he was listening to, or the story he was going to write next.

Philip Roth receives an honorary doctorate at the Jewish Theological Seminary’s commencement in New York on May 22, 2014. (Ellen Dubin Photography)

Tell me about your book’s subtitle, “Stung By Life.”

It’s a phrase I found in a eulogy Roth wrote for his friend Richard Stern. He said Stern was “stung by life,” and I thought, that’s Roth.

He was perpetually shocked by existence — by what people do, by what happens to them, by what happens to him. Zuckerman, his alter ego, is defined by ambivalence — about women, about Jewishness, about America. Roth described everything well, but ambivalence best of all.

You’ve written books of history, and biographies of other Jewish literary figures, including the Zionist thinker Ahad Ha’am and Isaac Rosenfield, the American-Jewish writer who died in 1956 when he was only 38. What challenges did you find writing about a figure like Roth, who was still alive when you began work on the book, and what do you think you brought to it that maybe others couldn’t?

I’ve written and taught biography for years. Roth spent his entire life writing about himself, but not telling the truth about himself. That puzzle fascinated me.

Some Jewish figures — Isaiah Berlin, for example — chose biographers who didn’t quite understand the Jewish stuff. I wanted to do the opposite. I wanted to understand him from the inside out.

I loved his work before I started. I love it even more now. Words were my way out of a world where answers were predetermined by Maimonides. Roth fought that battle too —against dogma, against certainty, through language.

Sometimes I think Roth’s gifts as a comedian have overshadowed other qualities of his work — for example, everyone who read “Portnoy” remembers the slapstick about masturbation, but I love his lyrical descriptions of his old Weequahic neighborhood in Newark and heading down to the park to watch “the men” play softball. Was he worried that he’d be shelved in the “humor” section of the bookstore?

He liked to say he was a comic writer in the tradition of Kafka and [Heinrich] Heine — not Shecky Greene, [the Catskills comedian].

But yes, he could be incredibly funny. In many ways, “The Ghost Writer” [1979], as beautiful and lyrical as it is, is all written in order for Philip to have that punchline about Anne Frank.

The book’s narrator, Nathan Zuckerman, a writer like the young Roth, imagines that Anne has survived and that he can heal a rift with his family by bringing her home as his fianceé.

“Nathan, is she Jewish?” “Yes, she is!” “But who is she?” “Anne Frank.” In many ways, those were the lines that begat that brilliant book.

I also feel people overlook how much he wrestles with the Jewish condition — and not just Jewish mother jokes or nostalgia for the old Weequahic neighborhood. In books like “The Counterlife” and “Operation Shylock” Roth was writing about Zionism, assimilation, extremism and the tension between Israel and the diaspora when few other serious novelists were. Does he deserve to be more widely read as part of the very current Jewish debate over these topics?

Yes. I think in sort of more conservative, traditional Jewish quarters, he ended up being seen as an enemy of the Jews. But thinking about your question, it’s hard to think of any piece of extraordinary fiction that’s really made its way into the Jewish communal debate.

But Roth actually entered emphatically into the Jewish conversation. At one point in the late 1980s, Roth gives an interview to his friend Asher Milbauer. And he admits that the Jewish readership is his primary readership. He says writing as an American Jew is akin to writing for a small country where culture is paramount. As for other readers, he said, ”I have virtually no sense of my impact on the general audience.”

How would you describe that impact, and why should he still be read and admired?

Because he closes his eyes to nothing. He looks straight at the things we’d rather look away from — sex, aging, death, hypocrisy, joy. He writes about the child of good parents, the lover, the son, the dying man — all the selves we carry.

He shows how truth and illusion coexist, how clarity is always fragile. And he does it with language that’s alive. That’s what endures.

Does he still feel relevant to you?

Completely. Even among his contemporaries — [John] Updike, Bellow — Roth feels less dated. Maybe that’s because he was never comfortable. He kept interrogating everything, including himself.

That’s why he’s still with us. The rest of us are still trying to catch up.

Learn about Philip Roth’s “Portnoy’s Complaint” and other classics in a new course from My Jewish Learning: “Funny Story! The Best Jewish Humor Books of the Past 75 Years.” Taught by Andrew Silow-Carroll, the four-session course starts on Monday, Oct. 27 at 6 p.m. ET. Register here.

As 1000+ rabbis sign anti-Mamdani letter, others decry mounting ‘red lines’ in Jewish communities

Two days after Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove delivered a sermon urging congregants to vote against Zohran Mamdani, rabbis across the country were asked to sign a letter quoting him.

By the time it was published Wednesday, 650 rabbis and cantors had done so, adding their names calling out the “political normalization” of anti-Zionism among figures like Mamdani, the New York City mayoral frontrunner.

By Friday, the letter had more than 1,000 signatories, making it one of the most-signed rabbinic letters in U.S. history.

But Cosgrove, the senior rabbi of Park Avenue Synagogue on the Upper East Side, was not one of them.

“As a policy, I do not sign group letters,” he said in an interview.

“My fear of such letters is they can flatten subjects and reduce complex issues to ‘Who’s on a letter and who’s not on a letter?’” he added. “There are other platforms that rabbis can give expression to their leadership.”

As the letter has ricocheted across the country and escaped from rabbis’ inboxes to their congregants’ social media feeds, it has ignited a wave of scrutiny, plaudits and recriminations. Some people have voiced relief or disappointment in seeing their rabbi’s name on the list — or on not seeing it.

“Jewish communities are circulating spreadsheets of who signed and who didn’t,” wrote Rabbi Shira Koch Epstein in an essay describing what she said was “a painful public reckoning” taking place both publicly and privately.

“I am not sleeping. These red lines are so dangerous,” responded Rabbi Lauren Grabelle Hermann, of Manhattan’s Society for the Advancement of Judaism, in one of dozens of comments representing a wide range of views. Hermann devoted her Yom Kippur sermon earlier this month to calling on her community to “become an antidote to the polarization and fragmentation in our broader Jewish community and society.”

Now, facing renewed pressure from their congregants over the letter, some New York City rabbis are articulating alternative strategies for responding to a political moment that many Jews are experiencing as fraught and high-stakes.

Rabbi Angela Buchdahl wrote to all members of Central Synagogue, the Manhattan Reform congregation where she is senior rabbi, to explain why they would not find her among the letter’s signatories.

“As a Central clergy team, we have spoken from the pulpit in multiple past sermons and will continue to take a clear, unambiguous position on antisemitism, on anti-Zionist rhetoric, and on sharing our deep support for Israel,” she wrote.

But, citing the importance of “separation of church and state,” Buchdahl wrote that “it is up to each of us to vote our conscience.”

“There are political organizations, including Jewish ones, where electoral politics is the core mission. Get involved,” she wrote. “Central Synagogue, however, is a Jewish spiritual home and we want to keep it that way. It remains our conviction that political endorsements of candidates are not in the best interest of our congregation, community, or country.”

Rabbi Jeremy Kalmanofsky of the Conservative synagogue Congregation Ansche Chesed on the Upper West Side sent out a letter of his own to congregants. He said he would not be voting for Mamdani but did not believe it was his role to tell them how to vote. And he raised concerns about what he said was the “shearing off of liberal from conservative liberal communities,” saying that Jews of all political outlooks should be able to pray and act together.

“The Torah commands lo titgodedu, traditionally interpreted to mean, don’t fragment yourselves into factions,” Kalmanofsky wrote. “I fear this happening to Jews. Frankly, I fear it more than I fear an anti-Zionist mayor.”

Rabbi Adam Mintz, who leads the recently rebranded Modern Orthodox congregation Shtiebel @ JCC, said he’d signed a smaller letter from Manhattan Orthodox rabbis urging the importance of voting. But Mintz felt this letter was outside his role.

“I’m a rabbi. I don’t want to take a political stand,” he said. “I understand that some people feel strongly and they want to take a political stand. I think that’s OK, but that’s not my role.”

Rabbi Michelle Dardashti of Kane Street Synagogue, an egalitarian Conservative synagogue in Brooklyn, did not sign the letter, either. She instead took a different approach to addressing her congregants in the lead-up to the election, hosting about 80 of them Tuesday night for an evening of dialogue.

Members representing a spectrum of views took turns sharing questions and concerns ahead of the election. Dardashti said congregants, despite conflicting views, were “deeply engaged and passionate, and spoke beautifully and respectfully.”

“I understand my rabbinic role to be one that creates space for people to learn from each other’s different experiences, and therefore perspectives,” she said.

Some Jewish leaders and groups outright opposed the letter and its message, rather than considering it an ill-advised strategy. Bend the Arc, a progressive Jewish organization that endorsed Mamdani, released a statement excoriating the letter and its signatories for distracting from what it said was the real issue: Donald Trump.

“These Jewish leaders are doing Trump and the MAGA movement’s work for them: dividing our pro-democracy movement at a time when we need to be united to beat back fascism,” the statement read.

Josh Whinston, a rabbi in Ann Arbor, Michigan, expressed skepticism on social media about the letter’s origin and intentions, and noted that he did not sign it.

“This was not a call for moral clarity; it was a political move aimed at influencing a local race in New York City,” he wrote.

Upon first reading it, Whinston wrote that he “agreed with parts of what it said,” and that he “considered signing.” But, hoping to learn more about the Jewish Majority, the group behind the letter, Whinston wrote, “The site offered no substance. There was no mission, no vision, no leadership, no staff.”

The Jewish Majority’s goal, as stated on its website, is to counterbalance left-wing “fringe groups” like Jewish Voice for Peace and Jews for Racial and Economic Justice, which they say “weaponize the Jewish identity of some of their members to call for policy recommendations that are rejected by the overwhelming majority of the Jewish community.”

The executive director of the Jewish Majority, Jonathan Schulman, is a former longtime AIPAC staffer. In an interview, Schulman said he wrote the letter’s first draft before it underwent rounds of edits from about 40 rabbis of different denominations.

The inspiration came when “Rabbi Cosgrove’s sermon started making the rounds,” he said, adding, “By Sunday morning, rabbis were reaching out to me saying, ‘This is the kind of sentiment we’re feeling all over the country.’”

Unlike Cosgrove’s sermon, which included an endorsement of Andrew Cuomo, the letter does not mention either of Mamdani’s opponents. It does, however, say that political figures like “Zohran Mamdani refuse to condemn violent slogans, deny Israel’s legitimacy, and accuse the Jewish state of genocide,” and calls on Americans to “stand up for candidates who reject antisemitic and anti-Zionist rhetoric, and who affirm Israel’s right to exist in peace and security.”

Schulman recalled being told, “‘There’s the issue of Zohran Mamdani and calls to globalize the intifada and all this, but there’s anti-Zionist candidates running for mayor in Somerville, Massachusetts, in Minneapolis, Seattle — this is becoming normalized, this is becoming mainstream.’”

Rabbi Mark Miller of Temple Beth El in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, is one of the rabbis who helped edit the letter. He said part of his goal was to help clarify its nature as being national rather than local.

“This was not an attempt for the rest of us to get involved in New York politics,” Miller said. “It’s highlighting it, but the issue is that everywhere we are, this is a concern.”

Signatories on the letter include rabbis from across the United States, and even outside the country.

Rabbi Brigitte Rosenberg, the senior rabbi of a Reform congregation in St. Louis, signed the letter, and said the message about anti-Zionism resonated with her on a national level.

“Mamdani was the big race that was talked about in this, but it’s come up in other races, right?” Rosenberg said, pointing to the comeback bid of “Squad” member Cori Bush to represent St. Louis in Congress.

Rabbi Jeremy Barras from Miami said a number of his congregants have residences in New York, and “they’re just terrified.”

“But I would’ve signed it if it was the same issue in any city in America,” Barras said. “It just happens to be true that we’re a little more sensitive because so many of our families have connections in New York.”

Both Barras and Rosenberg said they couldn’t remember an open letter signed by this many rabbis. There have in fact been examples of open letters being signed by 1,000-plus rabbis, including an appeal to open Palestine to Jews in 1945; a 2017 letter calling on Trump to support refugees and a letter from earlier this year demanding Israel stop “using starvation as a weapon of war.”

Yehuda Kurtzer, co-president of the Shalom Hartman Institute, affirmed that open letters like the one distributed by the Jewish Majority are nothing new, and said there is “definitely a tension that emerges” for those expected to sign. Endorsements from the pulpit, on the other hand, are “new terrain,” he said, noting the Trump administration’s decision to stop enforcement of an IRS rule barring political endorsements from religious institutions.

“We felt pretty strongly that rabbis should not generally do this, and there’s a whole variety of reasons,” Kurtzer said. “It’s a plausible scenario that politicians will start doing quid pro quos with religious leaders around their needs. Once you do it once there’s an expectation that you’ll do it all the time.”

Some of the rabbis who signed say they weren’t making a partisan political statement. Ammiel Hirsch, senior rabbi of Stephen Wise Free Synagogue on the Upper West Side and the leader of a Zionist organization within the Reform movement, acknowledged “worries” about alienating some congregants. But, like others who’ve come out against Mamdani, Hirsch said it was non-partisan to speak out against someone whose rhetoric could compromise Jewish safety.

“There’s always the risk that people will understand you in a partisan way, especially since we’re living in such a hyper-partisan atmosphere now,” Hirsch said. “But it’s a risk that we have to take because the stakes are so high.”

Rabbi Joshua Davidson of Manhattan’s Temple Emanu-El made a similar point. “I’m not going to tell people who they ought to vote for. But I do think it’s important for me to let them know what I think they ought to be thinking about when they vote,” he said, pointing to issues like “the well-being of the State of Israel and the safety of the Jewish community.”

For Cosgrove, whose synagogue is located 20 blocks from Davidson’s, the division that’s arisen since his sermon is something to grieve.

“It deeply saddens me that, in a moment where the Jewish community should be thinking about the external threats that our community faces, that we should be spending an iota of energy on that which exacerbates any fault lines,” Cosgrove said.

The Jewish Museum has just completed a major renovation. Here are 7 highlights.

Following a yearlong, $14.5 million renovation, the Jewish Museum — which is housed a 1908 French Gothic mansion on Fifth Avenue — is opening two upgraded floors to the public.

Among the new features on the museum’s reimagined third and fourth floors: a new installation, “Identity, Culture and Community: Stories from the Collections of the Jewish Museum,” which spotlights 200 items from the museum’s permanent collection; four galleries for rotating exhibits and new acquisitions and the Pruzan Family Center for Learning, featuring art-making studios, a touch wall, and an interactive, simulated archaeological dig.

The renovation is the brainchild of the museum’s director, James Snyder, who assumed the helm of the 121-year-old institution in November 2023, following stints as the director of the Israel Museum and deputy director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The renovation “gave us the opportunity to think through an entirely new narrative, an entirely new strategy for what we are all about,” Snyder said during a press event on Tuesday.

“These are complex times — they have been for a while. They’re getting more and more complex every day,” Snyder said. “Our job, particularly for culturally specific museums like this one, is to be the antidote to what’s really a pandemic today — to the xenophobia, the racism, the ignorance that is prevalent everywhere now.”

Here are seven things to see and do at the renovated Jewish Museum’s new galleries.

1. Marc Chagall’s “Self-Portrait with Palette” (1917)

Marc Chagall’s “Self-Portrait with Palette” (1917) is among the new acquisitions at the Jewish Museum. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

This self-portrait by the lauded Jewish artist is in the Cubist style. An oil on canvas, the painting shows Chagall as a young man holding a brush and palette, with his hometown of Vitebsk (in today’s Belarus) in the background.

When the portrait was painted — during the Russian Revolution — Chagall had just returned home after three years at a Parisian art school in order to marry his childhood sweetheart, Bella Rosenfeld, who modeled for many of his works.

The painting, a new acquisition by the museum, was previously in a private collection. It was last publicly exhibited at the Tefaf New York art fair at the Park Avenue Armory in 2022. It hangs “in conversation” with a newly acquired piece by Alice Neel, titled “Nazis Murder Jews,” from 1936, an unusually non-abstract work by Mark Rothko that shows a deconstructed crucifix, and three paintings by Romanian-Israeli painter Reuven Rubin.

2. 130+ Hanukkah lamps, from ancient times to the present

A glass case of more than 130 Hanukkah lamps is part of the Jewish Museum’s identity and culture exhibit, drawn from the museum’s collection. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

The Jewish Museum has more than 1,400 Hanukkah menorahs in its collection, and as part of its new, fourth-floor learning center, more than 130 are on display in a space that is open to a double-height gallery on the third floor.

The installation — featuring menorahs from across the globe, antiquity to the present day — is meant to accentuate “the central meaning of light as a symbol of enlightenment and hope across cultures,” per a press release.

Particular highlights include oil lamps from the 2nd to 1st century BCE, as well as a “Menurkey” — a turkey-shaped menorah, devised by 9-year-old Asher Weintraub in 2013, when Thanksgiving and Hanukkah overlapped for the first time since 1888.

3. “The Return of the Volunteer from the Wars of Liberation to His Family Still Living in Accordance with Old Customs” (1833–34) by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim

‘The Return of the Volunteer from the Wars of Liberation to His Family Still Living in Accordance with Old Customs” by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim. (Courtesy The Jewish Museum)

Considered to be the first Jewish painter in the modern era, Moritz Daniel Oppenheim — born in 1800 in Hanau, Germany — is known for being the first Jew to receive a formal arts education in Europe.

Many of Oppenheim’s works — which are on view at the museum as part of its permanent collection — showcase intimate portraits of Jewish life in Europe. Considered his masterpiece, “The Return of the Volunteer,” depicts a young German Jewish man returning home after helping defend Germany against the Napoleonic armies just as his family is welcoming Shabbat. (Note the challah and kiddush cup on the table.)

Oppenheim created the painting during a time of civil unrest following the 1830 revolutions in France, when some German states passed repressive legislation against the Jews. Per the Jewish Museum, “This painting has been interpreted as a reminder to Germans of the significant role played by Jews in the Wars of Liberation, and its political overtones are unusual in the generally apolitical nature of Biedermeier art.”

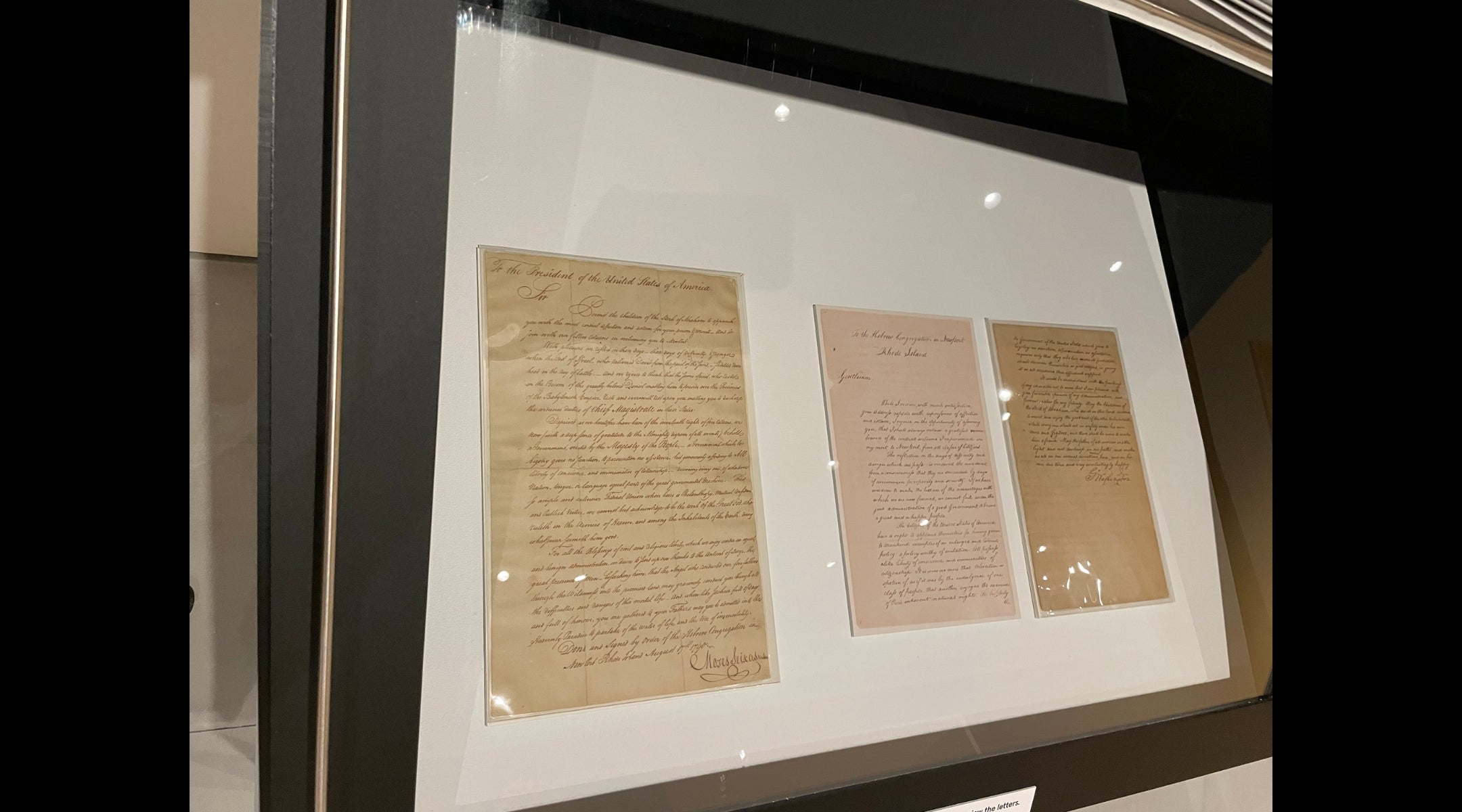

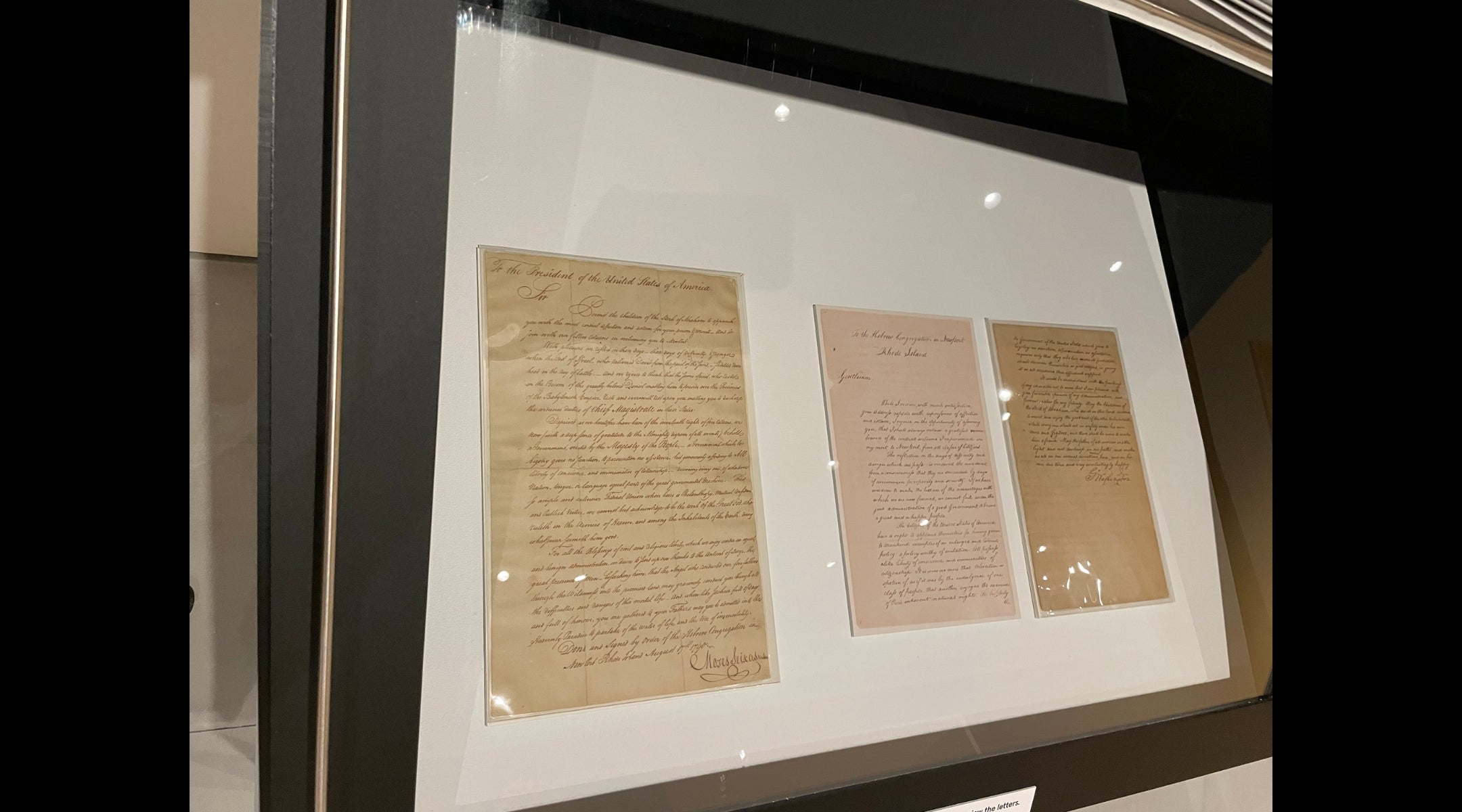

4. Letters between George Washington and Moses Seixas

A letter exchange between Touro Synagogue president Moses Seixas and American President George Washington. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

Part of the new “Identity, Culture and Community” exhibit is a section on Jews in the Colonial Era. A highlight here are letters from 1790 between new American President George Washington and Moses Seixas, the president of Jeshuat Israel of Newport, Rhode Island, now known as the Touro Synagogue — the oldest synagogue in the United States.

Washington came to Rhode Island after the state ratified the United States Constitution in order to promote the passing of the Bill of Rights; upon Washington’s arrival in Newport, Seixas read a letter aloud to the president, in which he expressed optimism at the freedom of religion that Americans would see in this new country.

“May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in this land continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants —,” Washington wrote in response, adding a quotation from scripture, “while everyone shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid.”

The letters are so delicate they’re kept under a window blind that visitors manually pull up and down, to minimize exposure to light.

5. A child-friendly mock archaeology dig

Visitors of all ages can dig for replicas of real ancient artifacts in the Jewish Museum’s newly renovated dig room. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

As part of the Pruzan Family Center for Learning, the Jewish Museum’s new mock archeology dig is three times larger than the previous version. Here, as part of the visitors can dig through four pits, each centered around a different era in time, for replicas of real artifacts, such as an Ottoman-era copper alloy coffeepot from Jerusalem, an ancient Roman oil lamp and a calcite-alabaster jar from ancient Egypt circa 1550 BCE.

The real versions of those artifacts — most of them newly on display in the room — are also on display, accompanied by kid-friendly language. Families are provided with an “Archaeologist’s Notebook” to keep track of their finds.

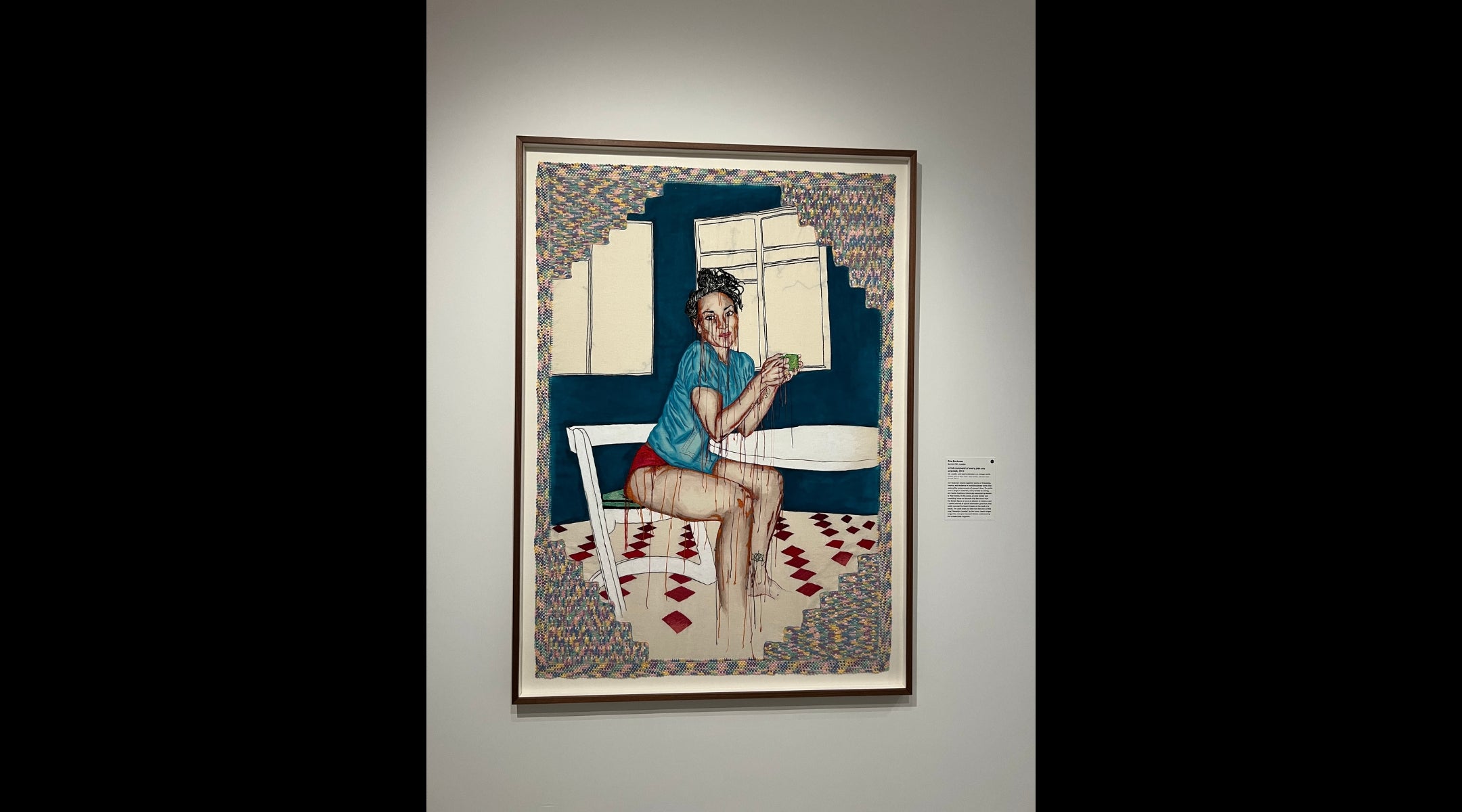

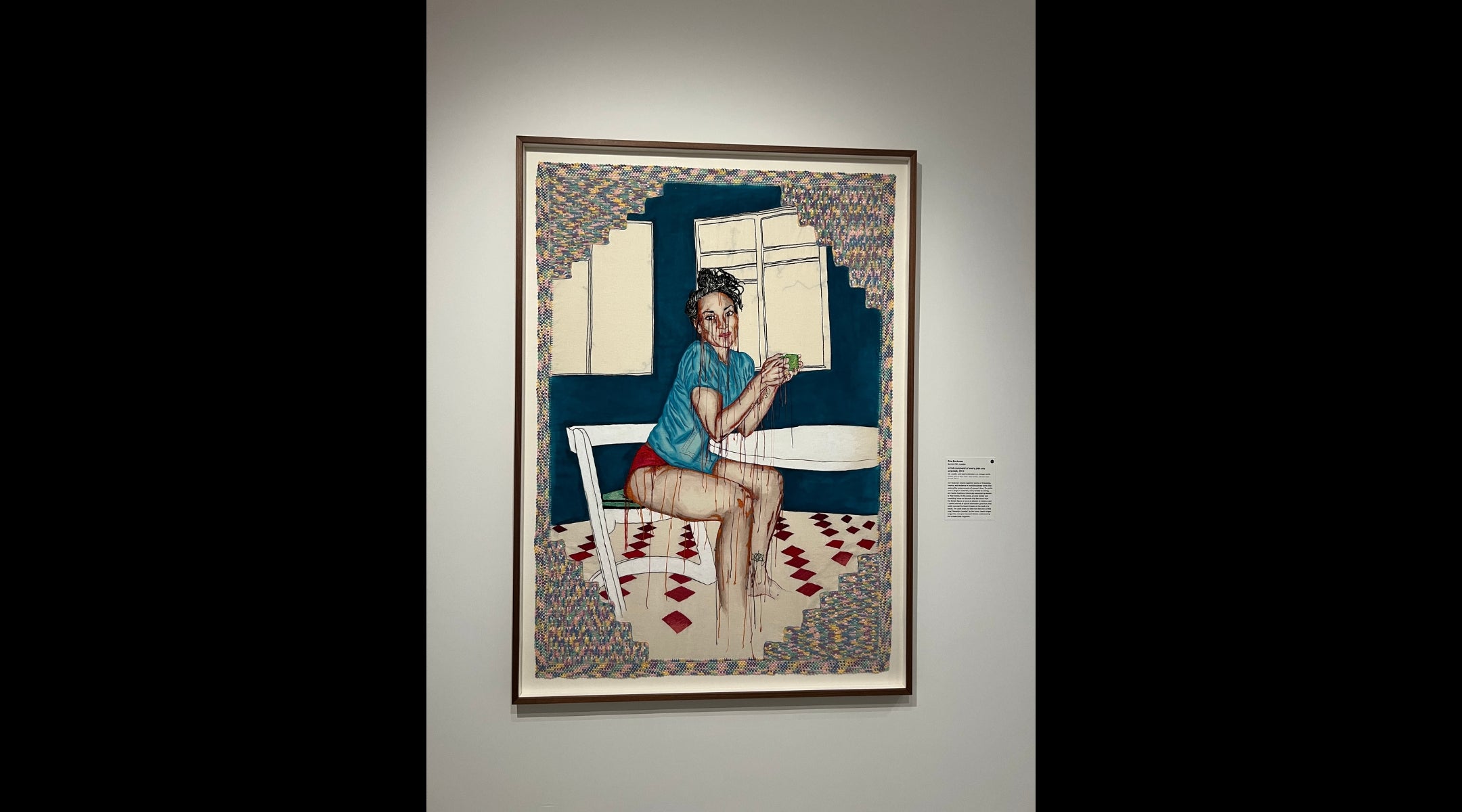

6. “in full command of every plan you wrecked” (2024) by Zoë Buckman

“in full command of every plan you wrecked” by Zoë Buckman is on view at the Jewish Museum as part of the third floor’s rotating exhibitions. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

Zoë Buckman, 40, is a British Jewish artist whose work has been featured in the UK’s National Portrait Gallery and who has emerged as a prominent voice among artists on antisemitism in the wake of the Gaza war. This ink, acrylic and hand-embroidered piece is Buckman’s debut at the Jewish Museum, which is part of her “Who by Fire” series exploring Jewish personhood.

Located on a third-floor gallery, Buckman’s work depicts a woman sitting on a chair; the piece’s name, “in full command of every plan you wrecked,” a reference to a Leonard Cohen lyric from “Alexandra Leaving.” The loose threads — typically found on the back of such woven pieces — subvert expectations of traditional feminine and domestic textile work.

7. A retrospective on the early works of Anish Kapoor

Some of the early sculptural pigment works of Anish Kapoor at the Jewish Museum. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

Born in India in 1954 to a Punjabi Hindu father and an Iraqi Jewish mother from Mumbai, Anish Kapoor rose to prominence as an artist exploring matter, non-matter, space and voids. “Anish Kapoor: Early Works,” on view until Feb. 26, 2026, is the first American museum presentation showcasing Kapoor’s works from the late 1970s and early 1980s, “when he was still the classic starving artist,” per the New York Times.

Snyder and Kapoor — a winner of the prestigious Genesis Prize — have previously collaborated on exhibits at MoMA and the Israel Museum; the Jewish Museum exhibit opens on Friday alongside the museum’s newly reimagined floors. “He is about this narrative of the experience of the Diaspora and what it does to artists,” Snyder said of Kapoor.

Advocates decry ‘pogrom on the playground’ after Jewish children targeted in Chicago suburb on Oct. 7

A heavily Jewish suburb of Chicago has condemned antisemitism after an investigation confirmed reports that a group of Jewish children were attacked with pellet guns and subjected to antisemitic rhetoric in a public park earlier this month.

The incident took place on Oct. 7, the first day of the Jewish holiday of Sukkot and the second anniversary of the Hamas attack on Israel, in Shawnee Park, which is located blocks from a number of the town’s Orthodox synagogues.

It occurred when five children between the ages of 8 and 13, were approached by another group of children who asked if they were Jewish, according to the Chicago Jewish Alliance, an advocacy group that has taken an aggressive stance against antisemitism in Chicagoland.

When the children replied that they were Jewish, the group of roughly 20 assailants, who were between the ages of 12 and 14, then allegedly shouted “f—k Israel” and “you are baby killers so we are going to kill you” at the children and shot gel gun pellets from a recreational gun at them, according to a Facebook post by Daniel and Robyn Burgher Ackerman, the parents of a 13-year-old girl who was among the victims.

The Ackermans posted what they said was their first public account of the incident on Thursday, after an investigation by the town was completed. The Village of Skokie said this week that police had responded to the scene on Oct. 7, where the children alleged to have participated in the incident were identified and interviewed and a police report was filed.

The case was “closed” following the investigation’s conclusion, according to the Village of Skokie. It did not name any actions it was taking in response but said the incident had been documented and shared with the Human Relations Commission, which would later issue a recommendation based on its findings.

“There is no place for hate in Skokie,” said Mayor Ann Tennes in a statement. “Our community has long been built on respect, inclusion and care for one another. The Village remains committed to standing against antisemitism and all forms of bias, and to ensuring that Skokie continues to be a safe and welcoming place for everyone.”

The Skokie Park District said it had been made aware of the incident only this week. “We do not tolerate racist remarks or acts of violence in our parks,” it said in a statement issued Thursday. “We are prepared to work with the Village of Skokie’s Human Relations Commission and the Skokie Police Department as part of a community-wide effort to address this hateful occurrence and prevent these behaviors in the future.”

The Ackermans and the Chicago Jewish Alliance say they are concerned that the incident is not being treated with the appropriate urgency, citing a lack of evidence of any disciplinary action against the children who participated.

In a post on Facebook Friday, the Skokie Police Department addressed community members’ “frustration and concerns” with the incident, saying that although details available to the public were limited because the perpetrators were minors, it had been classified as a hate crime.

“Due to the antisemitic statements demonstrating bias as a likely motivator in the battery involving the gel blaster, the Department has classified this incident as a hate crime,” the post read. “This classification was made upon the Department’s initial investigation into this incident on October 7.”

Police said that one minor had reported being struck in the leg by a gel pellet, and that while the investigation into the incident has concluded, the resolution of this incident is ongoing.

Following the police announcement, the Chicago Jewish Alliance shifted the focus of a planned appearance at the Village of Skokie Board meeting on Nov. 3 to demand increased transparency between law enforcement and the Skokie community, according to Daniel Schwartz, the group’s president.

“While we appreciate this overdue recognition, it is important to reflect on why it required public outcry to reach this point. The classification of a hate crime should never depend on media coverage or community pressure. It should be immediate, transparent, and guided by moral clarity,” wrote Schwartz in a statement.

He said that during the assault, the assailants allegedly told the victims that they would “get a real gun and kill you Jews.”

Schwartz, who referred to the incident as a “pogrom on the playground,” said the incident had “really disturbed” the local Jewish community.

“I think this hits a nerve, because it happened on Oct. 7, it happened to children, it happened to children in Skokie, Illinois, which has a very dense Jewish population, and then the municipality itself, similar to what we saw in 1940s Germany, was almost like — there was just no justice or repercussion,” said Schwartz.

He added that the parents of the victims of the attack are also seeking legal counsel over the incident.

“This was not ‘kids being kids.’ This was a targeted, violent antisemitic attack on Jewish minors- in their synagogue dresses on a Jewish holiday,” the Ackermans wrote. “The fact that it happened on October 7th—exactly two years after the October 7, 2023 massacre of Jews in Israel—makes it even more chilling.”

Netanyahu and far-right ministers do damage control on West Bank vote and Saudi Arabia comments that angered Trump

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu sought to distance himself Thursday from a Knesset vote that granted preliminary approval to a bill annexing the West Bank, after the measure drew strong condemnation from the White House.

At the same time, a far-right Israeli lawmaker apologized after making a dismissive and, some said, offensive comment about Saudi Arabia, putting him at odds with the White House’s goal of brokering relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia.

The backtracking comes at a time when the Israelis are facing fierce pressure from President Donald Trump and his administration not to jeopardize a fragile Gaza ceasefire that took hold earlier this month.

“The Knesset vote on annexation was a deliberate political provocation by the opposition to sow discord during Vice President JD Vance’s visit to Israel,” wrote Netanyahu’s office in a post on X.

His post came soon after Vice President J.D. Vance, who departed from Israel on Thursday after a visit to “monitor” Israel’s ceasefire with Hamas, said the vote amounted to an “insult,” adding that if it was a political stunt, then “it was a very stupid political stunt.”

Trump has vowed not to allow Israel to annex the West Bank, a goal of the Israeli right that is seen as a red line for Arab states hoping to see an independent Palestinian state in the future.

“It won’t happen because I gave my word to the Arab countries,” Trump said in an interview with Time magazine published Thursday. “Israel would lose all of its support from the United States if that happened.”

The exchange comes days as Israeli settlers launched a volley of attacks on Palestinian activists and olive harvesters this week, leaving one woman in the hospital, adding to growing violence in the West Bank.

Netanyahu’s distancing from the Knesset bills told only part of the story. He claimed that the “Likud party and the religious parties did not vote for these bills,” two parties from his coalition, but while it was true that his Likud Party did not back the bills, others in his coalition, including Otzma Yehudit and Religious Zionists, did and represented the majority of their support. Still, the bills cannot achieve full passage without Netanyahu’s buy-in, which he said he would not give.

Bezalel Smotrich, the finance minister who leads the Religious Zionists, was at the center of the other flareup on Thursday when he declared at a conference, “If Saudi Arabia tells us ‘normalization in exchange for a Palestinian state,’ friends — no thank you. Keep riding camels in the desert.”

Smotrich’s remarks were made ahead of a planned meeting between Trump and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman at the White House next month to discuss normalization between Arab countries and Israel.

After drawing public criticism from others in Israeli politics, Smotrich later apologized for the remarks in a post on X, writing, “My statement about Saudi Arabia was definitely not successful and I regret the insult it caused.

But he said he would not retract his concern about Palestinian statehood, which the Saudis support. “However, at the same time, I expect the Saudis not to harm us and not to deny the heritage, tradition and rights of the Jewish people to their historic homeland in Judea and Samaria and to establish true peace with us,” he wrote.

Israeli Diaspora Minister Amichai Chikli also appeared to criticize Smotrich’s comment in a post on X, writing, “I firmly oppose the establishment of a Palestinian State. That said, it does not mean we should insult a potential ally🇸🇦.”

He then extended an invitation of his own for a new relationship — ending the week after he brought a far-right British personality to Israel against the objections of Britain’s organized Jewish community.

“Incidentally, we’re also pleased to be hosting a unique camel race in the Negev together with the Bedouin community in just a few weeks — and we warmly invite our Saudi friends to join us,” Chikli wrote.

Cuomo slammed for ‘Islamophobia’ after interview with Jewish shock jock Sid Rosenberg

This piece first ran as part of The Countdown, our daily newsletter rounding up all the developments in the New York City mayor’s race. Sign up here to get it in your inbox. There are 11 days to the election.

😱 Cuomo accused

-

Andrew Cuomo has been widely accused of Islamophobia after a radio interview Thursday with Sid Rosenberg, a Jewish conservative shock jock. (We profiled Rosenberg last year after he emerged as one of Donald Trump’s leading Jewish surrogates.)

-

Cuomo was arguing that Mamdani lacked the experience to lead New York City through crises. “God forbid another 9/11,” he said to Rosenberg, who has hosted the former governor three times in recent days. “Can you imagine Mamdani in the seat?”

-

Rosenberg replied, “Yeah, I could. He’d be cheering.” Earlier in the program, Rosenberg called Mamdani a “terrorist.”

-

Cuomo laughed and said, “That’s another problem.”

-

Mamdani slammed the exchange shortly after in an interview with PIX11. “This is disgusting, he said. “This is Andrew Cuomo’s final moments in public life and he’s choosing to spend them making racist attacks on the person who would be the first Muslim to lead this city.” He added that Cuomo’s remarks “smeared and slandered” the more than 1 million Muslims living in New York City.

-

Rebukes also rained down from leading New York Democrats, including some, including Gov. Kathy Hochul, Rep. Dan Goldman and Rep. Ritchie Torres, who have previously expressed concern about Mamdani’s rhetoric on Israel.

-

Hochul told Cuomo to “get out of the gutter,” Goldman accused him of “naked Islamophobia” and Torres said the comments were “beyond disgusting and disgraceful.”

-

Rep. Jerry Nadler, who along with Hochul has endorsed Mamdani, also referenced New York’s line against antisemitism in his response. “Imagine if this kind of bigotry was used against any other faith — Jewish or Christian New Yorkers. Would we roll over and accept it?” he said.

-

Asked about the interview hours later, Cuomo said it was Rosenberg who used the controversial language. He added that he had in mind Mamdani’s interview earlier this year with Hasan Piker, a Twitch streamer who has been accused of antisemitism and once said that America “deserved 9/11.”

-

In the first mayoral debate last week, Mamdani said Piker’s comments on 9/11 were “objectionable and reprehensible.”

🏆 Adams endorses Cuomo

-

Weeks after saying that Cuomo was “a snake and a liar,” Mayor Eric Adams endorsed him and called him a “brother” on Thursday.

-

“Brothers fight,” said Adams, who last month quit his defiant reelection bid dogged by low polling numbers, at a press conference with Cuomo in Harlem. “When families are attacked, brothers come together.”

-

Adams said he was driven to unite with Cuomo against Mamdani in part because Mamdani declined to condemn the phrase “globalize the intifada” during the primary.

-

He then suggested there was a link between Mamdani and Islamic extremists. “New York can’t be Europe, folks. I don’t know what is wrong with people. You see what’s playing out in other countries because of Islamic extremism,” he said.

-

Meanwhile, Rep. Hakeem Jeffries praised Mamdani’s promise to retain NYPD police chief Jessica Tisch and said he planned to speak with Mamdani this weekend, raising the prospect of a possible endorsement.

🚺 ‘Hot Girls for Cuomo’

-

Pro-Israel influencer Emily Austin, who was born in New York to Israeli parents, launched a campaign she called “Hot Girls for Cuomo” this week.

-

Austin urged her viewers to vote for Cuomo before interviewing him on her YouTube show. She had particular encouragement for one demographic: “If you are a hot girl for Andrew Cuomo, I want to hear from you,” she said.

-

Austin said she was persuaded to vote for the Democrat because she believed he could beat Mamdani, calling herself “as conservative as it gets.” She previously interviewed Trump.

-

But someone appears to have gotten to the web address HotGirlsForCuomo.com before Austin. The link directs to the New York attorney general’s investigation that validated sexual harassment allegations against Cuomo in 2021.

📝 Jewish letters against Mamdani

-

Michael Oren, a former Israeli ambassador to the United States, joined other prominent Jewish voices urging New Yorkers to vote against Mamdani in recent days.

-

More than 1,000 rabbis across the country have now signed a letter that said a Mamdani victory would threaten “the safety and dignity of Jews in every city.” One rabbi said the letter has divided Jewish leaders and communities.

-

In a new open letter, Oren said, “There can be no obscuring the fact that the candidate wants to see my state, my family, and the home of the world’s largest Jewish community erased from the map.”

-

Oren claimed that Mamdani said Israel has no right to exist, and said his “singling out” of Israel was antisemitic. Mamdani has repeatedly said that Israel has a right to exist, though he has expressed reservations about its right to exist as a Jewish state, saying it should exist “with equal rights for all.”

-

Read up on everything else Mamdani has said about Israel, Jews and antisemitism here.

Katherine Janus Kahn, illustrator of ‘Sammy Spider’ Jewish children’s books, dies at 83

More than 30 years ago, a colorful little eight-legged spider named Sammy made his picture book debut and scurried into the homes of Jewish families across the country.

Sammy Spider and his mother live in a house with a young Jewish boy named Josh Shapiro and his family. Starting with “Sammy Spider’s First Hanukkah,” he romped through Jewish holidays, prayers and practices across more than two dozen books — all illustrated with bright watercolor collages that have made the books instantly recognizable to generations of Jewish children.

That was the work of Katherine Janus Kahn, who died Oct. 6 at age 83.

Janus Kahn, a fine artist also noted for her works on political justice and women’s issues, illustrated more than 50 books for Kar-Ben, a publishing house for Jewish children’s books that counts the “Sammy Spider” franchise as among its best-selling.

“We are heartbroken,” Kar-Ben said in a Facebook post, adding, “We are profoundly grateful for her legacy, and for the countless stories and memories she leaves behind.”

David Lerner is the CEO of Lerner Publishing Group, the parent company of Kar-Ben, the country’s largest publisher of Jewish children’s books.

“Katherine’s art and storytelling helped shape the landscape of Jewish children’s literature,” he said in an email. “Her books have been recognized with many national awards, honoring her creative vision and her lasting impact.”

Kar-Ben was a tiny company when it first connected with Janus Kahn in the early 1990s. She had drawn attention with her paper-cut illustrations for “The Family Haggadah,” which became a bestseller when it was published in 1987, and the publisher wanted to pair her with an author named Sylvia Rouss who had dreamed up a little spider with a big Jewish future.

“We liked her many styles and thought the collage work would be fun for Sammy’s Hanukkah,” Judye Groner, Kar-Ben’s founder, wrote in an email. “We had no idea that Sammy would become a children’s favorite character featured in over 20 books.”

In that first title, the curious little arachnid spies the young Josh celebrating Hanukkah, wishes he could warm his spider legs on the menorah and wants to spin the colorful dreidels that Josh gets every night.

“Silly Sammy. Spiders don’t light Hanukkah candles. Spiders spin webs,” his mother tells the disappointed Sammy. The catchy refrain repeats for Hanukkah’s eight nights when his mother gives Sammy eight spider socks spun with colorful dreidels, just like the ones Josh gets.

Over the next three decades, Sammy learned about empathy in “Sammy Spider’s First Mitzvah,” celebrated the entire Jewish holiday cycle from Rosh Hashanah to Shavuot and stowed away in Josh’s luggage in “Sammy Spider’s First Trip to Israel.” The most recent book, “Sammy Spider’s Big Book of Jewish Holidays,” came out this year and compiles many of the classic stories that are now widely distributed to Jewish families through PJ Library.

Janus Kahn’s art brought the characters sparkling to life, according to Heidi Rabinowitz, past president of the Association of Jewish Libraries and host of the Book of Life Podcast about Jewish children’s literature.

“Her rainbow-soaked collage artwork give the Sammy Spider books a huge advantage,” Rabinowitz wrote in an email. “They make Sammy and Mrs. Spider friendly and even beautiful, completely removing the ‘ick factor’ from their arachnid identity.”

For Janus Kahn, who studied art at Jerusalem’s Bezalel Academy after graduating from the University of Chicago, the work connected to her core identity. In a 2017 watercolor essay, she said her study at Bezalel came after she volunteered to support Israel during the Six-Day War in 1967 and headed to Israel, where she said “reconciliation felt possible,” even after the war’s end.

“My Judaism and my books are tied together so integrally that I don’t think I could ever untie them,” she said in a 2013 video with Rouss that showed her demonstrating her artistic techniques in her home studio.

Among her other titles was “The Hardest Word: A Yom Kippur Story,” published in 2001, the first in a series written by Jacqueline Jules about a Ziz, a large, magnificently colored Jewish mythological bird. Like Sammy Spider, the Ziz books struck a chord and are now part of the canon of Jewish children’s books.

“She was just so creative,” recalled Jules, who had multiple books illustrated by Janus Kahn. Their first book together, “Once Upon a Shabbos,” published by Kar-Ben in 1998, was about a bear who gets lost in Brooklyn just before the start of Shabbat. Jules was struck by how Janus Kahn’s illustrations added new texture to a story inspired by an Appalachian folktale.

She and Janus Kahn realized they lived near each other in the Washington, D.C., area. After meeting at an event for the book, they headed to a coffee shop for a two-hour conversation that launched a decades-long professional relationship and close friendship. They socialized together, along with Groner, who also lived nearby.

The two were paired up for the Ziz books, another series that has charmed generations of Jewish children. For those books, Janus Kahn created a fanciful creature using paints rather than collage.

“She borrowed different characteristics from a variety of birds. The legs were from a flamingo, the feet were from a rooster,” Jules said.

Now, the Ziz has taken on a life of its own, making appearances in synagogue plays and other programs based on the books. Just a few weeks ago, Jules saw a photo of someone who dressed up as the Ziz at a synagogue event for Yom Kippur, in keeping with the first book’s theme.

Janus-Kahn would often join Jules for a Ziz storytelling at Jewish venues, bringing a feltboard to embellish the Ziz props and a hand-made Ziz puppet that Jules used. At one memorable event, at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Janus Kahn arrived with two colorful feather boas, Jules recalled.

“She made the Ziz come alive,” she said.

With Janus Kahn’s death, Jules, Groner and Rouss not only lost the gifted master illustrator for their books. They have also lost a treasured friend of many decades.

“Kathy was a gift and our friendship was a gift,” Jules said.

Janus Kahn is survived by her husband, David Kahn, and a son, Robert.

Our communal definition of Jewish security is too limited. We need a wider one.

On Saturday mornings, I walk through metal detectors on my way into synagogue. I’m aware of why they’re there, and I feel grateful they exist.

My husband, who works at a Jewish day school, is grateful too for the security and cameras keeping an eye on the campus. In 2025, our places of faith require us to invest thoughtfully in safety.

These actions make us more safe, but is that all we need to feel more secure? If you ask me, the way we talk about “security” falls short.

In July, Jewish leaders applauded when Congress approved $274.5 million in federal security funding for nonprofits, including synagogues and Jewish community centers. The applause was deserved. In an era of heightened antisemitism, these dollars matter.

And yet, if our definition of “Jewish security” starts at cameras and locks, and stops with security guards, then it is incomplete. True security must also mean that Jews can afford to see a doctor, put food on the table, and secure a living wage.

The same budget Congress passed in July also cost Jewish households billions of dollars in security, literally. Alongside countless cuts, the administration eliminated more than $1 trillion from healthcare programs that make it possible for millions of Americans to fill a diabetes prescription or access preventative care like a mammogram. The largest of those programs is Medicaid.

I remember when my grandfather’s care needs for his Alzheimer’s ramped up, and I wondered, who was paying for this? For so many families, including mine, the answer in that moment is Medicaid. Today, one in 11 American Jews relies on it. Medicaid is the insurance that provides Holocaust survivors with home health care aids, covers therapy for young queer Jews at Jewish Family Service agencies, and ensures Jewish babies are born without their parents adding the bill to their credit card debt. For more than 650,000 Jews, Medicaid is security. For them, a cut to Medicaid is not abstract; it’s a threat to their lives.

When I read the results of a new study on American Jewish finances, I had to read them again. Twenty-nine percent of Jews say they are struggling or just barely making ends meet, up from 20 percent in 2020. If you’re feeling stretched right now, it is not just you.

And painfully, while 66% of Jews with financial stability believe the community takes care of people in need, only 39 percent of low-income Jews agree. We are a community that prides itself on mutual responsibility, but we are falling short.

For generations, Jews were at the forefront of labor movements, fighting for fair wages and economic justice. Today, that spirit continues with groups like the Network of Jewish Human Service Agencies, which organized for months against the healthcare cuts embedded in HR 1. But the issue seemed to be missing or swept aside from the radar of the broader Jewish community.

Despite our people’s history being marked by our lack of access to assets, I sometimes feel like I’m inside an antisemitic cartoon when I jokingly remind people that yes, low-income Jews do exist and at high rates. I myself grew up in a household that at times relied on government assistance like SNAP and free school lunch. I know how it feels to sit in synagogue and wonder if anyone sees you, and your or your friends’ financial fears.

As a former case manager, CEO of a national hunger organization, and now Jewish poverty expert, I have learned that change does not happen alone. Our rabbis, our philanthropists, our institutions, and yes, our government partners must all widen the definition of Jewish security.

We recently marked Sukkot, a holiday that puts front and center how fragile security can be. We should remember that our ancestors never defined security by walls alone. They defined it by covenant—by the promise that no one would be left to wander alone. As philosopher Michael Waltzer reminds us, “wherever you are, there too is Egypt,” a place where someone is oppressed and burdened.

Waltzer reminds us that a better world is possible, and the only way to get there is by joining together.

When I walk through those metal detectors on Shabbat, I’m grateful. And I know that for many, security requires not just protection but stability. Jewish security means that every person in our community can live with healthcare, access to a thriving Jewish life, and someone to call when things get hard. That is the covenant we renew each time we care for one another.

‘The church is asleep right now’: Ted Cruz calls on Christians to confront right-wing antisemitism

Sen. Ted Cruz used his keynote address at a major gathering for Christian supporters of Israel this week to warn of “a growing cancer” of antisemitism on the right, which he said church leaders are failing to address.

“I’m here to tell you, in the last six months, I have seen antisemitism rising on the right in a way I have never seen in my entire life,” Cruz said, speaking on Sunday at a megachurch in San Antonio, led by John Hagee, the founder of Christians United for Israel, which claims to have more than 10 million members.

He continued, “The work that CUFI does is desperately, desperately needed, but I’m here to tell you, the church is asleep right now.”

In the days around Cruz’s speech at Hagee’s 45th annual Night to Honor Israel, a cluster of conservative voices made similar appeals, arguing that antisemitism inside parts of the right can no longer be waved away as fringe. Essays in The Free Press and Tablet mapped how extremist figures and ideas have been normalized and the Jewish educational center and think tank Tikvah warned of a “clear faction” hostile to Israel and Judaism.

In The Free Press, conservative columnist Eli Lake published an essay titled “How Nick Fuentes Went Mainstream,” arguing that the far-right activist — long shunned for racist and antisemitic rhetoric — has lately been welcomed by a roster of popular podcasts and livestreams. In Lake’s telling, the “stigma” around Fuentes has “melted away,” an index of how the Overton window has shifted inside parts of the online right.

At Tablet, a first-person essay by a libertarian insider headlined “Hitler Is Back in Style,” traced what the author describes as a libertarian-to-alt-right pipeline that, over the past decade, normalized conspiratorial thinking about Jews and open flirtations with Hitler apologetics. The piece is both confessional and diagnostic, naming podcast ecosystems and ideological crosscurrents that, the author argues, have turned “antiwar” rhetoric into reflexive anti-Israel sentiment and a broader hostility to Jews.

Meanwhile, Tikvah, one of the most prominent right-wing groups in the Jewish world, noted in an email to supporters Thursday that it has tracked the same trend.

“Today, there is a clear faction of the right that is overtly hostile to Israel and to Judaism. And though small, it is no longer marginal or possible to ignore,” wrote Avi Snyder, a senior director at Tikvah.

The organization pointed to a body of essays it began publishing in 2023, warning that some on the right were reviving old suspicions about Jewish loyalty, casting the U.S.-Israel alliance as a trap, and disputing the moral superiority of the Allied fight in World War II.

In the background is the aftershock of Charlie Kirk’s assassination last month, which unleashed a torrent of conspiracies that quickly turned antisemitic in parts of the right’s online ecosystem. Fact-checkers documented a flood of false claims, while some influencers toyed with theories about Israeli or “Mossad” involvement — rhetoric with enough popular traction that Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, felt compelled to issue a rebuttal. The swirl reinforced how fast fringe ideas migrate in today’s media sphere, even as prosecutors in Utah have charged a suspect and outlined a motive that has nothing to do with Israel.

In his speech, Cruz noted he has talked to Netanyahu about declining support for Israel on the right — and that the two men see the issue differently.

He recounted a recent conversation with the Israeli prime minister, saying that Netanyahu’s first instinct was to chalk much of it up to foreign amplification from places like Qatar and Iran — bots and paid misinformation networks.

Cruz pushed back: “I said, ‘Mr. Prime Minister, yes, but no. Yes, Qatar and Iran are clearly paying for it, and there are bots, and they are putting real money behind it, but I am telling you, this is real, it is organic, these are real human beings, and it is spreading.’”

Later in his address, Cruz highlighted the drift’s theological dimension. He warned of a resurgence of replacement theology, which he characterized as a “lie that the promises God made to Israel and the people of Israel are somehow no longer good, they are no longer valid.”

According to replacement theology, the Israelites were supplanted as God’s chosen people once the Christian church was founded.

Cruz didn’t blame anyone by name, but his comments come as figures with long records of inflammatory commentary toward Jews or Israel have continued to gain oxygen. Fuentes has rebounded from ostracism to high-visibility bookings; Tucker Carlson draws millions of viewers amplifying narratives that edge into Jew-baiting; and Candace Owens’ conspiratorial comments about Israel continue to pull audiences.

Together they form a feedback loop in which algorithmic reach and controversy reward edgier takes — and make it harder for party actors to draw lines.

Adding to the fray is last week’s Young Republicans leak, a Politico exposé of a Telegram chat where early-career GOP activists traded racist slurs, joked about gas chambers and praised Hitler. The episode prompted firings, the shutdown of state Young Republican chapters and bipartisan condemnation. But Vice President J.D. Vance downplayed the messages as immature “jokes” and urged critics to “grow up,” a stance that itself became part of the week’s debate over whether the right will police its own.

Soon after Kirk’s assassination, Rich Goldberg, a senior adviser at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and a veteran of Republican politics, urged more policing on the right. In a post on X, he called on conservatives to stop booking Carlson, calling the former Fox News host’s posture toward Jews and Israel “a disease that is poisoning the Republican Party.”

He added, “It needs to be met with a decision by those we call ‘leaders’ to stop platforming him (and those who echo such vile sentiments).”

More than a month later, the most important right-wing leader in the country, Donald Trump, has yet to weigh in.

Season 2 of ‘Nobody Wants This’ arrives on Netflix, returning Rabbi Noah and interfaith dilemmas to TV screens

When the first season of the surprise hit “Nobody Wants This” ended last year, viewers were left with a cliffhanger about the unlikely couple at the center of the story: Would Joanne convert to be with Rabbi Noah? Would they be together at all?

Now, the second season has dropped, bringing the immediate revelation in the first episode that, while their relationship has survived, no decision has been made. Thus begins another 10-episode season showcasing the travails of an interfaith Los Angeles couple and their families, portraying culture clashes and synagogue politics as the backdrop to both universal relationship road bumps and steamy romance.

In addition to Adam Brody as Rabbi Noah Roklov, two other Jewish actors step in to play rabbis — Alex Karpovsky as another Rabbi Noah and Seth Rogen as Rabbi Neil, the leader of a congregation more progressive than the original Rabbi Noah’s Temple Chai.

Over the course of the season, the show depicts a Purim celebration, a Shabbat dinner, a baby-naming ceremony, fraught dilemmas over the inclusion of non-Jewish partners in Jewish communities and, yes, a decision to convert to Judaism. (Our colleagues at Kveller have compiled an episode-by-episode analysis and opened a group-chat on Substack.)

The first season drew plaudits for casually celebrating Jewish life while also eliciting criticism for its characterization of Jewish women and surface-level depictions of Jewish practice. Those continue into Season 2, according to Evelyn Frick at Hey Alma, who chronicles a litany of shortcomings in an essay raising questions about whether the show has a positive view of Judaism at all.

A Los Angeles rabbi who served as a consultant on the first season and told us at the time that he had worked to ensure the Jewish content was “done with authenticity and respect” is not listed in the credits this time around.

Still, the show has generated a staunch fan base whose members are treating the launch of the new season with some of the fervor surrounding a Taylor Swift album drop. A splashy event drew hundreds to the 92nd Street Y in New York City on Wednesday to screen the first episode together, and a block party complete with photo opportunities and exclusive merchandise is planned for Saturday in Los Angeles.