Dara Horn’s gonzo, time-traveling children’s Passover book wants people to love living Jews

“All of my books are the same book,” said Dara Horn, the author of seven novels and the 2021 essay collection, “People Love Dead Jews,” which may be the most talked-about Jewish book of the past several years.

The subject, she said, is time — how Jews mark it, how they preserve it, how they understand where a moment goes once it is passed. Her 2006 debut, “A World to Come,” toggles between present-day New Jersey and 1920’s Russia. Her 2018 novel “Eternal Life,” meanwhile, is about an immortal woman, born in Jerusalem, who experiences countless lives over 2,000 years.

She took the title of her 2009 Civil War novel, “All Other Nights,” from the Passover Haggadah, which she calls a book about “the collapse of time,” expressed in its injunction that “in every generation a person is obligated to see themselves as if they left Egypt.”

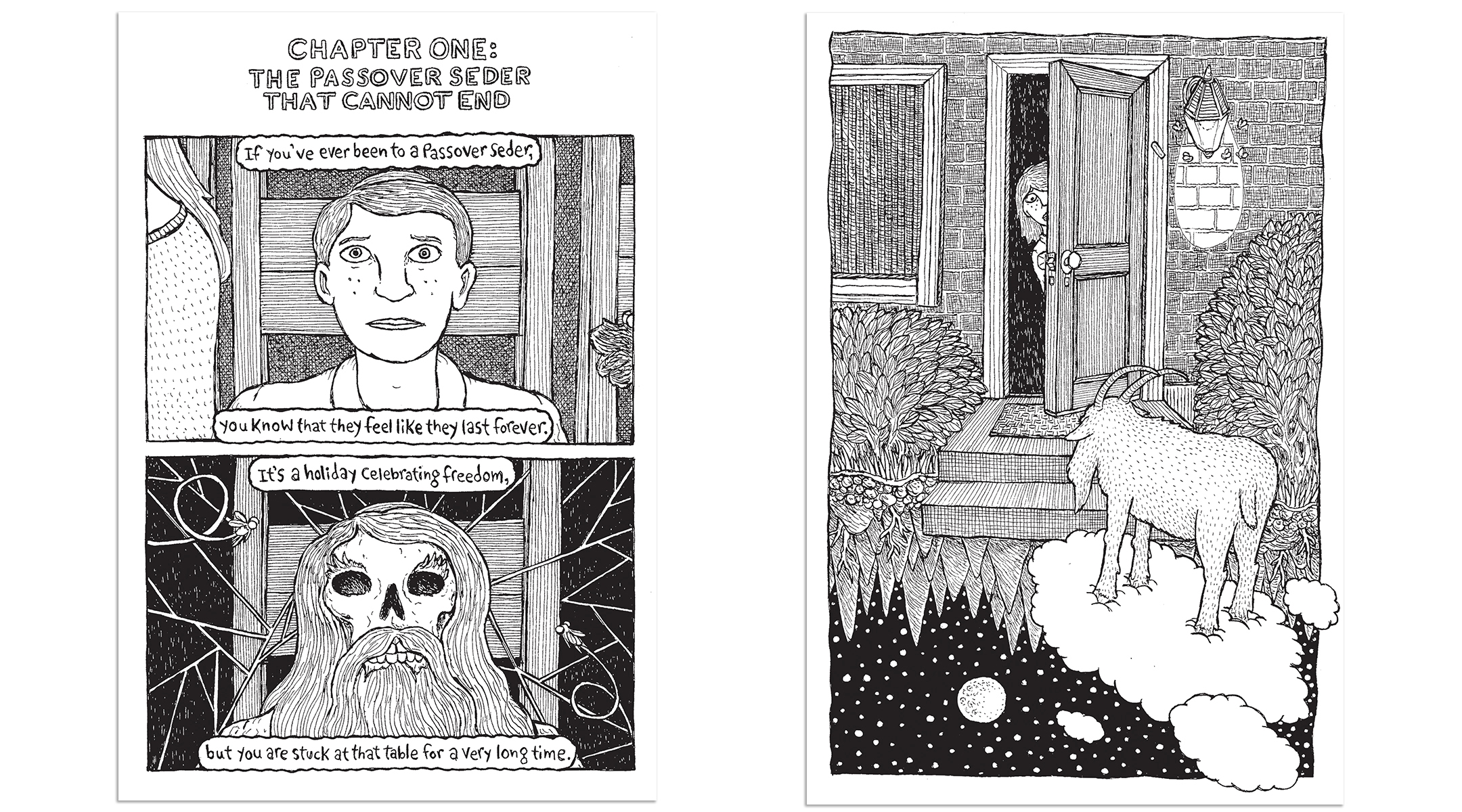

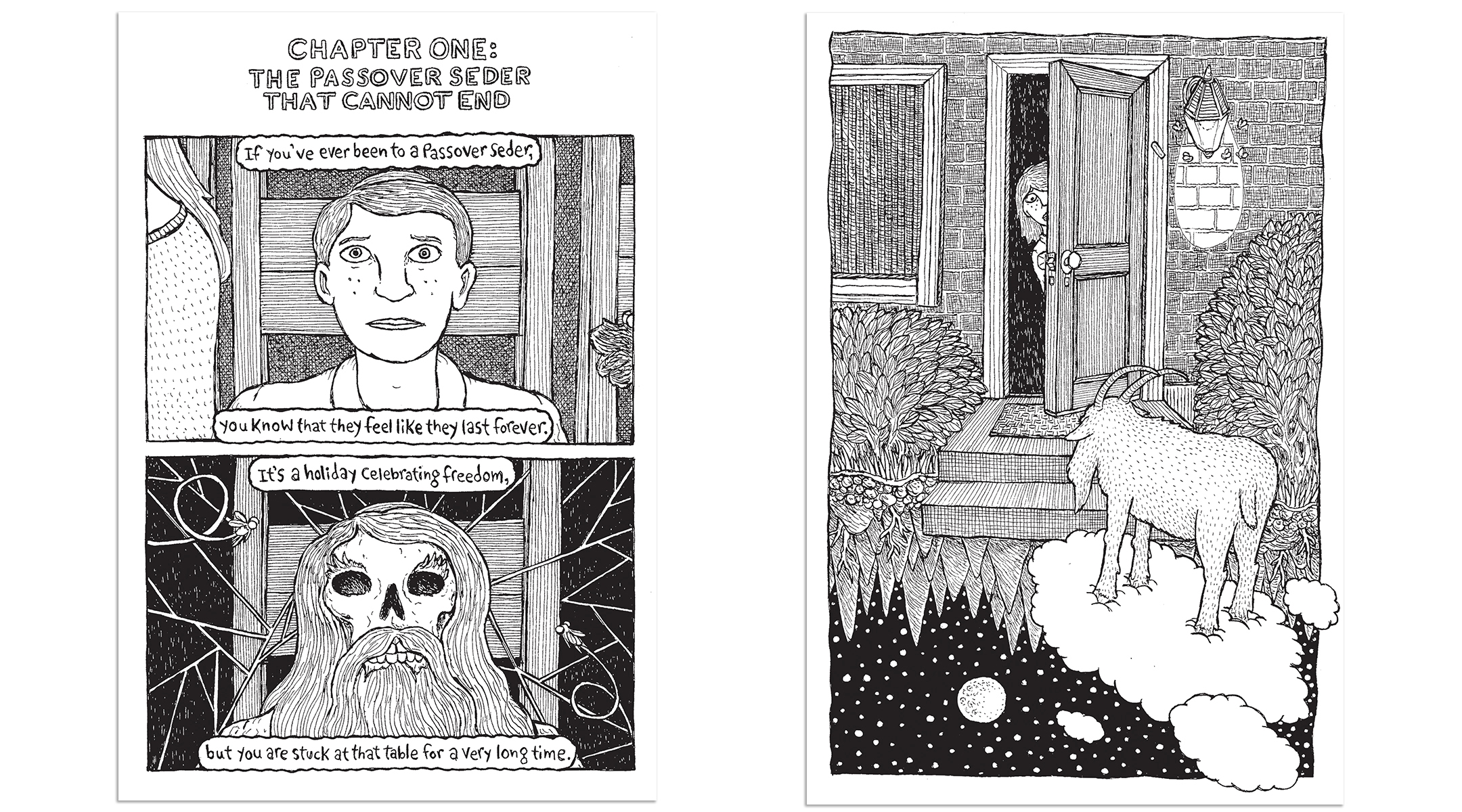

It’s a verse that becomes literal in her latest book, the middle-grade graphic novel “One Little Goat: A Passover Catastrophe.” In it, a young boy escapes a seemingly endless family seder in the company of a talking goat, who drags him back through a “hole in interdimensional space-time” and to the seder tables of historically iconic Jews, including Sigmund Freud, the 16th-century philanthropist Doña Gracia Nasi and the Talmudic tag team known as Rav and Shmuel.

The book is both a history lesson, and a lesson about history.

“The seder is not just about the Exodus from Egypt. It’s also a commemoration of a commemoration of a commemoration,” said Horn, noting how the traditional Haggadah itself includes descriptions of at least two prior seders, the very first one in Egypt and one held in the Land of Israel after the destruction of the Second Temple. Quoting the late American historian Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Horn said Jewish culture makes a distinction between history and memory, and Jews are more interested in memory: investing a historical event with eternal, inheritable meaning.

“When I say I write about time, I mean specifically, how do we live as mortals in a world that outlasts us?” she said. “That’s the central question that I’m exploring as a writer.”

History and memory were the subjects of “People Love Dead Jews,” where Horn proposes that in its fascination with the ways Jews suffered and died, the world either overlooks or devalues the way they actually lived and live. Even well-meaning efforts like Holocaust-education mandates and Shoah memorials ignore the layers and layers of Jewish history and complexity, leaving Jews as convenient abstractions for antisemites and conspiracy theorists.

The conversation sparked by the book — “‘People Love Dead Jews’ ate my life,” she jokes — turned the novelist and Hebrew and Yiddish scholar into a go-to expert on the recent rise in antisemitism. An alumna of Harvard, she gave an interview to a Congressional committee as a member of Harvard’s Antisemitism Advisory Group, formed in the wake of Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel. In recent months she launched a nonprofit, Mosaic Persuasion, which aims to supplement Holocaust and history of religion units in K-12 education with curricula about the foundations of Jewish civilization and the causes of antisemitism.

“There are 29 states in this country where people are required by law to learn in school that Jews are people who were murdered,” she said, referring to Holocaust education mandates. “There’s not a single state in this country where anyone is required to learn, like, who are Jews? What’s Israel? What the hell do they have to do with the Middle East? We’ve outsourced that to TikTok.”

The art by Theo Ellsworth for “One Little Goat” leans into the dark themes of the Passover story, and the dry humor of Horn’s text. (Theo Ellsworth; Norton Young Readers)

“One Little Goat” appears to be adjacent to that project — helping middle-schoolers understand the way their own family history is an accumulation of Jewish lives and experiences reaching back through time and marked each year at the seder table.

The story was inspired by two seders that Horn, who was raised and still lives in Short Hills, New Jersey, grew up attending. At the first, hosted by her parents, Horn and her three siblings would perform songs and skits, riffing on pop culture. The second she describes as a “large multigenerational gathering” that included Holocaust survivors, including some who had participated in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising on Passover of 1943, and former Soviet “refuseniks” were active in the Free Soviet Jewry movement.

Although frustrated that the kids played only a supporting role in the second seder, it left her with a kind of vision. “I felt like the room I was in was a lighted box that’s sitting on a tower of lighted boxes of other seders, including the seders that these people at this table have been at in the past,” she said.

The idea germinated for years before she contacted the decorated graphic novelist and illustrator Theo Ellsworth, a favorite of her children, and suggested they collaborate. Ellsworth, who is not Jewish, seemed to get it: If he wasn’t familiar with the Passover story, he understood its potential as a children’s adventure. Horn calls their book a “portal” story, like the Harry Potter books or C.S. Lewis’s Narnia tales, in which children slip through a passage into a fantastic world beyond.

“That’s so resonant for children because children’s lives are really small, and they’re completely managed by the adults in their lives,” said Horn. “That’s why children are looking for that access point to a life bigger than theirs.”

Horn said Ellsworth’s art — black and white, heavily inked, with an underground comics sensibility — appealed to her because it wasn’t “cute and cuddly.” Which raises the question: When are children ready to encounter a Jewish history of persecution and slaughter?

One answer is provided during the seder itself, which often ends with the traditional song “Chad Gadya,” or one little goat in Aramaic. It’s a “cumulative” song about a baby goat that is eaten by a cat, who’s killed by a dog, who’s beaten with a stick, culminating with the Angel of Death being slain by God. One interpretation is that the goat represents the Jewish people, and the climax of the song signals the redemption of the Jews. It’s a dark theme smuggled into an upbeat if macabre children’s song.

Making light of the seder’s darker themes is a Passover tradition all its own, and Horn is on board with it.

“By the time children are old enough to appreciate [the darkness], they own the story. They’re characters in the story, and they know that about themselves and that this is a story about us,” said Horn.

Horn embraces that darkness in her book, which includes an appearance or two by the Angel of Death. Horn recalls that the seder in the Torah is described as the Night of Watching. It takes place before the actual flight from Egypt, with the Jews at the table uncertain if they will survive.

“I can’t look at that scene anymore, of that first seder, without thinking of a ma’amad, the bomb shelters and safe rooms, where people in Israel were hiding on Oct. 7, and where everybody goes during missile attacks, where you’re hiding with your family trying to wait out the Angel of Death,” she said. “That’s where my mind was when we were finishing the book.”

Horn’s own seders are hardly grim affairs. She, her husband and four children stage extravaganzas, with a sort of Passover funhouse experience in the basement, laser lights and fog machines to simulate the parting of the Red Sea, and homemade movie and television parodies.

For Horn, Passover is a story about how Jews lived and how they survived. The history of persecution can’t be avoided but it is only part of the story.

Before “People Love Dead Jews,” said Horn, she would speak in bookstores about her novels and ask the audience two questions: How many people can name four concentration camps? And, how many people can name four Yiddish writers?

Most could answer the first question and few could answer the second.

“I’d say, ‘85% of the [Jews] killed in those concentration camps were Yiddish speakers. This is a very literary culture. Why do you care so much about how these people died when you really don’t care about how these people lived?’

“What I find really important about Jewish history is not this litany of horror — which I don’t think you can avoid talking about — but that the story of Jewish life is about this amazing creative resilience.”

Why I turned down an invitation to speak at Temple Emanu-El’s 180th anniversary Shabbat service

I was thrilled and deeply honored when I got an invitation to participate in Congregation Emanu-El’s 180th anniversary Shabbat service. This historic synagogue, where I began my rabbinate, is foundational to American Reform Judaism, and was the congregation of early Reform thinkers that inspire me today, including Rabbis Kauffmann Kohler, David Einhorn, and Judah Magnes.

But when I received more details about the service, where I would have had a speaking role, I thought again. I find Zionist elements in regular Reform worship — such as the Israeli flag on the bimah or a prayer for Israel — uncomfortable but not a deal-breaker for attendance. But Israeli President Isaac Herzog was listed as a speaker at the Emanu-El service, to be followed by communal singing of “Hatikvah,” Israel’s national anthem.

My qualms about Herzog, who many see as more moderate than the far right currently driving Israel’s war effort, stemmed from his statements immediately following Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023, attack. Herzog publicly blamed the entire Palestinian population of Gaza for Hamas’s actions, asserting collective responsibility due to their not rising up against Hamas. Though he also said in that appearance that there is no justification for killing innocent civilians, and that Israel would prosecute its response according to international law (a claim that has not been borne out), his statement was cited by the International Court of Justice as proof that Palestinians had plausible grounds for protection from genocide. Now, as Israel renews its war effort in Gaza, Herzog’s objections have centered on the risk to Israeli hostages and soldiers, not to Gazans.

Further, the inclusion of the Israeli national anthem in the service felt like a bridge too far. I do not believe expressions of nationalism — whether Israeli, American or other — have a rightful place in worship services. Adding Hatikvah alongside other prayers as part of worship also works towards the total conflation of American Jews with Israel. There is no stronger sign of loyalty to a nation than singing a national anthem before that nation’s flag — being part of a room full of American Jews doing so, especially as Israel has redoubled its military efforts, announced plans to seize large swaths of Gaza, and killed hundreds of Palestinians in the past week, goes against my core beliefs.

At Emanu-El, I valued our diversity and the synagogue’s historic openness. For some, Zionism was core to their Judaism. For others, it was anathema. In fact, Emanu-El has a proud history of holding both. In 1943, Rabbi Samuel H. Goldenson established the American Council for Judaism, my current employer, at the very address of Emanu-El, in a bid to maintain a Judaism free from nationalism and Zionism in the Reform movement. He remained the cherished senior rabbi for four more years, and when he announced his retirement, the congregation reportedly prevailed on him to remain for another year.

Inspired by the same anti-Zionist values, I have worked with a board of committed Reform Jews to renew the ACJ for our contemporary post-denominational Jewish world as its executive director. So I was initially torn between hoping that my presence at the 180th anniversary celebration might bridge divides, demonstrating that diverse views could coexist respectfully within our community, and fear that it would signal tacit support for a politician and a regime that I believe is anathema to Reform Jewish values. But seeing Herzog and Hatikvah on the agenda signaled to me that explicit support for Israel’s current actions would be prominent and expected of attendees.

Community is often thought of as a step between family and acquaintances. It bridges diverse beliefs, backgrounds and opinions, unified by shared purposes such as holidays, lifecycle events, study and celebration. Determining when community boundaries conflict with personal principles requires deep reflection. It demands clarity of personal principles, knowing when to allow those principles to bend, and knowing when the bending will turn to breaking.

As I reflected on my principles in considering the invitation – before learning what the service would consist of – I consulted with a rabbinic colleague also working in the Jewish left. “Isn’t part of the goal for Jews like us to be included in these sorts of things?” she asked. I agreed immediately. Both of us have experienced direct attacks from mainstream Jewish leaders and organizations for our stances, and the idea of instead being included in one of these spaces seemed to signal a shift. I also thought frequently of the words of the prophet Micah carved deeply in the building across the street from Emanu-El (once the home to the UAHC, the Reform Movement’s federation of institutions now known as the Union for Reform Judaism): “Do justly. Love mercy. And walk humbly with your God.”

For five years, I looked at this statement every day, and was inspired and motivated by it when I went to work at Congregation Emanu-El. These words guide not only my rabbinate, but my basic moral foundation as a Jewish person. I do not believe I would be upholding justice if I lent my presence to an event that is honoring Israel’s president, who continues to remain silent on the injustices being committed against Palestinians. It would certainly not show my commitment to mercy, given the ongoing merciless onslaughts in Gaza and Lebanon. And, to simply occupy a pulpit for the sake of doing so, even in contradiction to my own principles, would not embody humility, but rather hubris.

Today, my conscience demands that I decline participation in Emanu-El’s anniversary service. My decision is rooted firmly in the universal ethical core of Judaism first nurtured at this synagogue by generations of Jews committed to the messages of the prophets. I remain proud of my formative years at Emanu-El but urge my former community and all Jewish institutions to rediscover and recommit to Judaism’s universal ethical teachings.

As Netanyahu arrives in Budapest, Hungary announces exit from International Criminal Court

Hungary will withdraw from the International Criminal Court, the body that issued arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant last year.

The announcement preceded Netanyahu’s arrival in Budapest for a state visit, which comes as he faces multiple scandals at home and as Israel ramps up fighting in Gaza. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban is a doyen of the European populist right and a longtime Netanyahu ally.

Netanyahu’s trip to the United States last month was designed to bring Netanyahu together with President Donald Trump and to shore up support for Israel’s prosecution of its war in Gaza, and saw Trump pledge to take over the Gaza Strip and remove its Palestinian residents — promises that have recently gone unmentioned. Netanyahu’s visit to Hungary demonstrates that he is able to travel abroad despite the ICC warrant against him, issued over his alleged war conduct. The United States is not party to the ICC.

Hungary had already pledged not to arrest Netanyahu if he traveled to the country. Several other countries that are party to the ICC and ideological allies with Netanyahu have made the same pledge, as have the moderate leaders of other countries, including France, who argue that the warrants are invalid because Israel is not an ICC member.

Hillel CEO says he shares ‘concerns’ over campus deportations, calls for due process

Hillel International’s CEO expressed concern over the Trump administration’s plans to deport pro-Palestinian students and freeze federal funding to schools over campus antisemitism.

The statement from Hillel, the largest organization focused on Jewish students, is especially notable because the organization has often been at the forefront of calling out campus antisemitism and supporting pro-Israel students. Pro-Palestinian groups have targeted Hillel chapters or called on universities to cut ties with them in a number of instances.

Trump has sought to deport a string of campus activists in the name of protecting Jews. But Hillel CEO Adam Lehman said in a written address that the arrests — which have sparked a national controversy — could unfairly affect Jewish students and fuel antisemitism.

“For those expressing concerns over how current actions — such as deportations and withholding of grants for university research — are being implemented, we share those concerns,” he wrote.

Lehman wrote that he remained steadfastly opposed to campus antisemitism. He said that Hillel had documented a spike in campus antisemitism that has continued into this year, including hundreds of instances of antisemitic vandalism or threats of violence. He wrote, “First, for those who may be discounting and dismissing campus antisemitism as a real issue, we unfortunately know otherwise.”

But he called for due process for those accused of wrongdoing, and worried that Jewish students could bear the blame for Trump’s campus crackdown. He wrote:

For the benefit of Jewish students and all students, we believe it is essential that students, faculty, and staff violating laws and campus codes of conduct be held accountable for those destructive actions. At the same time, we also believe that due process for those accused of wrongdoing is essential — whether through mandated protections in legal settings or consistent, fair, and responsive disciplinary procedures at the university level.

We also share concerns over ways in which actions to combat campus antisemitism can actually fuel further antisemitism, feeding into longstanding tropes about outsized Jewish influence, and leading some people to unfairly hold Jewish students and faculty responsible for actions the government or others are choosing to pursue.

The administration’s recent actions, which have included a string of detainments of international students involved in pro-Palestinian protests and funding freezes at universities, have largely cited investigations into campus antisemitism as their impetus. While a broad range of Jewish groups have condemned the views and actions of the pro-Palestinian protesters, many opposed the efforts to deport them, or called for those detained to be afforded due process.

Lehman included a link in his address to an op-ed published yesterday by a former student president of Harvard Hillel who expressed disappointment over the administration’s recent threats to $9 billion in federal funding at the university. Trump has also frozen hundreds of millions of dollars of funding at Columbia and Princeton Universities.

“Despite my deep disappointment with many of my peers’ recent behavior, blanket federal funding cuts will inevitably fail to solve our University’s problems,” wrote senior Jacob M. Miller.

Lehman wrote that addressing antisemitism on campus necessitated a “multi-faceted” approach that went beyond legal moves by the administration: “While legal actions have a role to play, they are by no means a cure-all,” he wrote.

Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ includes 17% tariffs on Israeli imports, even as Israel cancels tariffs on US goods

The United States will impose 17% tariffs on goods imported from Israel under a sweeping new tariffs system that President Donald Trump unveiled on Wednesday.

The tariffs on Israeli goods are less than some Trump rolled out but greater than the 10% baseline that he is assessing on all imported products. They fall into the “reciprocal tariffs” bucket and represent half of the 33% tariffs that Israel has until now assessed on some U.S. goods. Many imports from the United States have not been taxed under a 1985 free-trade agreement.

Attempting to avert Trump’s targeting, the Israeli government on Tuesday abolished all tariffs on U.S. goods. It was not immediately clear whether Trump would adjust the tariffs on Israeli goods as a result, as he did for other countries that previously eliminated tariffs on U.S. goods under Trump’s trade pressure.

When Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced the decision on X, owner and Trump’s governing partner Elon Musk tweeted a two-emoji response: the American and Israeli flags, side by side.

The decision could raise prices on consumer goods including kosher food and Judaica that are produced in Israel. Israel is also a major exporter of technology, precious stones and medical supplies, sending products valued at more than $22 billion to the United States in 2024.

Trump argues that the tariffs are needed to reclaim money and respect that other countries have taken from the United States. His critics, including most mainstream economists, say they will wreak havoc on the global economy and translate largely into higher prices for U.S. consumers.

Brad Lander just cursed Andrew Cuomo in Yiddish, as NYC mayoral race intensifies

More than 100,000 people in New York City speak Yiddish. And if any of them were listening to Brad Lander on Wednesday, they may have wanted to cover their ears.

That’s because Lander, the city comptroller and a candidate for mayor, decided to clap back at a diss from Andrew Cuomo with a curse of his own — in Yiddish.

“A beyzer gzar zol er af dir kumen,” Lander, who is Jewish, said at a press conference.

It’s a phrase that translates literally to “May an evil decree come upon him.” But in the words of one Brooklyn political reporter, the rough translation is a little more colorful: “Get the f— out of here.”

Lander added, “Andrew Cuomo doesn’t get to tell me how to be Jewish.”

Lander was responding to a recent speech in which Cuomo addressed antisemitism — and hinted that some of his opponents, including Lander, were part of the problem.

“It’s very simple: anti-Zionism is antisemitism,” Cuomo said in his speech Tuesday at West Side Institutional Synagogue. He proceeded to accuse some of his rivals of fitting the bill, and claimed that Lander divested city funds from Israel — which Lander has denied.

The speech was the latest of several instances in which Cuomo, the frontrunner in New York’s crowded Democratic primary, has focused his campaign on Israel and antisemitism — which he called “the toughest issue that is facing the city of New York.” Among other things, Cuomo called for a ban on masks at protests and to more forcefully prosecute hate crimes.

The emphasis dates back to the aftermath of his 2021 resignation as governor, as he faced allegations of sexual harassment.

Cuomo has fiercely contested the allegations in court, but a recent profile in New York magazine said that he, a Catholic, performed a Jewish ritual to seek private atonement — casting his sins into the water, akin to the Rosh Hashanah practice of Tashlich.

“At one point, he said, he wrote down his sins on a piece of paper and tossed it into the waters off the Hamptons, where he was staying with his sister,” the article said. Its lead photo shows Cuomo wearing a yellow ribbon, symbolizing the plight of the Israeli hostages held by Hamas, as well as an Israeli-American flag pin.

Cuomo had sparked controversy among haredi Orthodox New Yorkers as governor for instituting measures to fight COVID-19 that, some felt, unfairly targeted haredi neighborhoods. He was also accused of allegedly saying “these people and their f—ing tree houses” while campaigning in a haredi neighborhood during Sukkot — a claim he denies.

But Cuomo has tried to cozy up to the Jewish community as 2025 approached. Back in the Hamptons last year, he kicked off a project fighting antisemitism, and even joined the legal team for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu as he faces charges of war crimes in the International Criminal Court.

Lander isn’t the only candidate who took flak from Cuomo in the synagogue speech. The ex-governor also condemned Zohran Mamdani, who has voiced support for the movement to boycott Israel. (Mamdani was also recently dubbed “DANGEROUS MAM” by the front page of the New York Post, which told its readers to “stop the anti-Israel forces” standing behind him.)

So will Cuomo’s bid to portray himself as the Big Apple’s “Shabbos goy” carry him to victory? Ruminating on his political fortunes to New York magazine, Cuomo reached for another Yiddish adage: “Men plan and God laughs.”

Jewish Princeton student accused of assault at protest last year is found not guilty

A Jewish Princeton senior and U.S. Army veteran accused of assaulting the school’s head of campus security during a pro-Palestinian protest last year has been found not guilty.

A New Jersey judge delivered the verdict Tuesday, the same day that Princeton’s president announced the school’s federal funding had been frozen by the Trump administration amid investigations into campus antisemitism.

Last April, David Piegaro, who self-describes as a “pro-Israel ‘citizen journalist,’” was attempting to film a sit-in on the campus when he had an altercation with Kenneth Strother Jr., the assistant vice president for public safety. Piegaro said he was not a part of the protests or counter-protests on Princeton’s campus, according to The New York Times.

Piegaro was attempting to follow Strother and two other people into a building adjacent to the sit-in when Strother blocked him from entry.

He proceeded to record the group and asked for Strother’s identity. In the recording of the incident, Piegaro says “don’t touch me” before the video cuts out, according to the Times.

Details over the ensuing altercation remain unclear. Strother asserted that Piegaro resisted arrest and Piegaro said he was the victim of assault, but the incident resulted in Piegaro falling down the steps of the building, where he was then arrested, according to the Times.

“The defendant, in my opinion, showed poor judgment in a tense moment, but it does not rise to the level of criminal recklessness,” said Judge John F. McCarthy III while issuing the verdict.

Following his arrest, Piegaro was barred from the campus for two weeks, a period during which he stayed with the director of Princeton’s Chabad House for a few days.

“In that environment, speaking specifically to the events of that day, when you have a whole host of public safety officers, administrators — I think doing their best — it’s not surprising that mistakes would get made,” Rabbi Eitan Webb told the Times.

Piegaro was arrested alongside 13 student protestors the day of the sit-in, making him one of 3,100 people arrested last spring surrounding pro-Palestinian protests on campuses across the country, according to the Times. The trials for the other students on trespassing charges are set for June.

Most recently, a number of international students have been detained or threatened to be deported by the Trump administration over their alleged involvement in pro Palestinian protests, including students at Tufts and Columbia Universities.

‘Qatar-gate’ and the complicated web of major scandals rocking Israel, explained

Not one but many interconnected scandals involving Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu are roiling the country right now.

They span everything from Israel’s courts to its intelligence agencies to suspicions of a Qatari plot. Police have questioned Netanyahu, two of his aides have been arrested and protests against him are still filling the streets. This week, the editor of the Jerusalem Post was also brought in for questioning.

And that’s beside ongoing debates over the Gaza war and the hostages held by Hamas.

Israeli news is often hectic and confusing. But if this week feels especially dizzying to you, you’re not alone. On Tuesday, the banner headline on one of Israel’s most-read papers blared, simply, “National Vertigo.”

What are these scandals? Are they interconnected? What do they mean for the war and the hostages in Gaza? Will Netanyahu keep his job? And what does Lindsey Graham have to do with all of this?

We explain it all here.

Why is Netanyahu’s office being investigated over Qatar?

The scandal lighting up Israel, more than any other, is known locally as “Qatar-gate.” (Yes, that’s what it’s called in Hebrew, too.) The short version of the story goes something like this:

Eli Feldstein was hired after Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023, attack as a spokesman for Netanyahu. At the very same time, allegedly, Feldstein was also being paid to represent the Qatari government — a longtime funder of Hamas — and to push Qatari messaging to Israeli journalists.

The man who oversaw Feldstein, longtime Netanyahu adviser Yonatan Urich, faces similar allegations. This week, another accusation surfaced: that Urich sent Qatari talking points as statements from Netanyahu’s office.

Both Feldstein and Urich have been arrested, and the investigation’s net has ensnared more people: Jay Footlik, a former Democratic adviser, reportedly arranged the Qatari payments to Feldstein.

On Tuesday, it emerged that Jerusalem Post editor-in-chief Zvika Klein was also being questioned under caution in the probe. Klein visited Qatar one year ago at the country’s invitation and spoke with senior officials there; he wrote that his trip there “reveals a nation striving for a larger purpose on the world stage.”

Israeli media had reported that Feldstein invited Klein to Qatar. In February, Klein denied that claim in a post on X, writing, “The truth is I have never met Feldstein” and that he spoke with Feldstein on the phone only following the Qatar visit.

He added, “The Qatari government is the one that contacted us, the Jerusalem Post — because they knew that we’re a balanced and influential publication that is read both among government officials and influential American Jews — as do many other countries, and we have no need for intermediaries.

One day earlier, Netanyahu himself was questioned. He has denied wrongdoing and said the investigation is politically motivated.

Isn’t Netanyahu embroiled in a lot of allegations? Why is this one blowing up?

Yes, Netanyahu has been on trial for corruption for years, in a series of cases that once scandalized Israel but have received relatively less attention recently in the country’s media and protests.

The Qatar scandal is different.

Qatar has funded Hamas and hosts Hamas’ leadership, who continued to use it as a home base after the terror group’s Oct. 7, 2023, attack. Qatar is also one of the countries mediating negotiations over the Israeli hostages Hamas is holding.

All of that makes Qatar something of an adversary to Israel — and key to the Israeli national interest. While some Israeli politicians have praised Qatar as a go-between, others have condemned it as a sponsor of terror.

It’s also far from the first example of Qatar using its billions to burnish its image internationally — whether by funding American universities, inviting their satellite campuses to its own soil, or hosting the World Cup in 2022. Those initiatives have invited scrutiny and criticism — and played into one of Qatar’s long-standing aims: For years, the oil-rich Gulf state has sought to establish itself as an indispensable bridge-builder and mediator in a fraught and violent region.

“Qatari money is like fingerprints that appear when an ultraviolet light turns on,” the Israeli journalist Matti Friedman wrote this week. He added, “But few suspected that the ultraviolet light would turn up a new fingerprint — in Israel itself.”

The concern is that if the prime minister’s aides are secretly working for the country that houses Hamas’ leaders, that may not bode well for Israeli security. Another twist: Amit Hadad, the lawyer representing Urich, also has another client: Netanyahu.

Will the investigation implicate Netanyahu? What’s he saying about it?

The prime minister has not been charged in Qatar-gate, but he was brought in for hours of questioning on Monday.

As in his corruption cases, the prime minister is denying any wrongdoing — and isn’t holding back. In a video on Monday, he called Feldstein and Urich “hostages” — a loaded term in Israel.

He claimed that the entire investigation is a ploy to take down his government.

“After an hour, they were out of questions,” he said of the police. “I said, ‘Show me materials, show me something.’ They had nothing to show. I was astounded. I knew this was a politically motivated investigation, but I didn’t understand to what extent. And they’re holding Yonatan Urich and Eli Feldstein, simply, as hostages.”

The comment raised eyebrows in Israel. “He knows no bottom,” tweeted liberal activist Yaya Fink, one of the prime minister’s longtime critics. “The only hostages are our 59 brothers and sisters who are abandoned in Hamas captivity.”

What does this have to do with Netanyahu firing the intelligence chief?

It depends who you ask. When Netanyahu announced two weeks ago that he would fire Ronen Bar, the head of the Shin Bet, Israel’s domestic intelligence agency, he said it was because he had “a continuing lack of confidence” in him — not because of the Qatar probe.

It is true that Netanyahu and Bar have reportedly clashed time and time again over the hostage negotiations. But given the timing of the decision, shortly after news of the Qatar investigation broke, Netanyahu’s critics alleged an ulterior motive.

“Netanyahu is firing Ronen Bar for only one reason — the ‘Qatar-gate’ investigation,” Israeli opposition leader Yair Lapid said on the same day as Netanyahu’s announcement. “For a year and a half, he saw no reason to fire him, but only when the investigation into Qatar’s infiltration of Netanyahu’s office and the funds transferred to his closest aides began did he suddenly feel an urgency to fire him immediately.”

A chunk of Israelis at large are sympathetic to that claim: Although Bar, who was in his position on Oct. 7, 2023, is unpopular, a poll found that about half of respondents say Netanyahu fired Bar over “Qatar-gate” — not because of his job performance. About a third said the decision was a result of Oct. 7.

The Supreme Court has frozen the termination until a hearing next week out of fear that the move was illegal. That fear succeeded an opinion by Israel’s attorney general, Gali Baharav-Miara — whom Netanyahu’s government is also pushing to fire.

Will Netanyahu obey the court?

That’s the question on everyone’s mind — and it depends in part on whether the court upholds the firing or strikes it down. But in the meantime, Netanyahu insists that he has the right to choose his own officials — and he’s forging ahead, with mixed results.

On Monday, he announced that Eli Sharvit, a vice admiral in Israel’s navy, would be the next Shin Bet chief. The appointment earned praise even from some Netanyahu critics, who praised Sharvit’s professionalism.

But then, one day later, Netanyahu flipped, and pulled Sharvit’s nomination. That about-face came after Netanyahu allies protested that Sharvit had opposed another Netanyahu effort — his quest to weaken the judiciary.

This is also where Lindsey Graham comes in. The Republican senator also objected to Sharvit — because the navy man recently wrote an op-ed, in Hebrew, criticizing President Donald Trump’s climate policy.

“While it is undeniably true that America has no better friend than Israel, the appointment of Eli Sharvit to be the new leader of the Shin Bet is beyond problematic,” Graham wrote. “There has never been a better supporter for the State of Israel than President Trump. The statements made by Eli Sharvit about President Trump and his policies will create unnecessary stress at a critical time.”

Netanyahu announced Wednesday that the Shin Bet’s deputy head would be its interim leader.

Is that why Israelis are protesting?

The short answer is yes. The long answer is yes — and they’re protesting other things, too.

Protesters massing outside Netanyahu’s Jerusalem residence have highlighted the Qatar scandal and opposed the firing of Bar. They’re also protesting other Netanyahu decisions that, they say, endanger Israel.

Antigovernment protests have been taking place for years in Israel for a variety of reasons, but they escalated two weeks ago when Netanyahu decided to end the ceasefire in Gaza and resume the war against Hamas, which recently intensified. Netanyahu said the new offensive is necessary to depose the terror group from Gaza. Protesters say it promises more war that will only endanger the hostages — instead of negotiating to bring them home.

Days later, another issue animated the protesters: A renewed, successful legislative push to enact a piece of Netanyahu’s long-desired judicial overhaul. Last week, the government passed a bill increasing politicians’ influence in selecting Supreme Court judges. Proponents of the move say it will make the court more responsive to the country. Opponents say it will politicize a previously professional system.

Whatever the issue at hand, the protests have been far from calm. The police, who are controlled by far-right National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, have clashed with protesters. On Monday, two policemen were filmed grabbing left-wing lawmaker Naama Lazimi by the arms and manhandling her at a protest as she screamed.

Will Netanyahu survive this scandal?

For now, yes. Despite the demonstrations, his parliamentary majority looks solid — and as long as he has a majority, he can stay in office. His government just passed a budget, which enables it to last until the next election, which is set to take place in late 2026.

Netanyahu is not popular: 70% of Israelis want him to resign, either right now or after the war ends. Most surveys show he’d lose a close election if one were held today. But his poll numbers have improved since Oct. 7, and he’s escaped from political peril many times before.

Still, challengers are girding themselves. Former Prime Minister Naftali Bennett, a former ally who was key to unseating Netanyahu in 2021, just announced that he was reentering politics.

Israel announces new offensive to seize ‘broad territories’ of Gaza Strip

Israel launched an offensive late Tuesday to seize “broad areas” of the Gaza Strip, signaling a prolonged military presence there.

The announcement by Defense Minister Israel Katz came as international outrage is mounting over the war. This week, United Nations officials said they discovered a “mass grave” with the bodies of 15 aid workers killed by Israel. Israel said the deaths occurred in a strike on terrorists using emergency vehicles.

The operation in southern Gaza began about two weeks after Israel ended a ceasefire with Hamas and resumed its war to defeat the terror group. Katz said it is meant to “crush and cleanse the area of terrorists and terror infrastructure, and to seize broad territories that will be added to Israel’s security zones in order to protect our combat forces and towns.”

Katz also said that the offensive is “first and foremost” meant to free all of the 59 hostages who remain in Gaza. The IDF’s chief of staff, Eyal Zamir, told troops on Wednesday, “The only thing that can stop us from advancing is the release of our hostages.”

In a statement Wednesday, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said troops were taking a new area called the Morag Corridor, adding it to the Philadelphi Corridor that Israel has held for nearly a year.

“We are now dividing the strip and increasing the pressure step by step, so that they will give us our hostages,” he said in a statement. “And as long as they do not give them to us, the pressure will increase until they do.”

Polls show that a majority of Israelis want the war to end with a deal to release the 59 hostages still held by Hamas in Gaza, 24 of whom are thought to be alive. The recent ceasefire, which lasted two months, saw dozens freed in exchange for a larger number of Palestinian security prisoners.

The Hostages and Missing Families Forum, which represents many of the hostages’ relatives, condemned the new offensive.

“Was a decision made to sacrifice the hostages for ‘seizing territory?’” the group said in a statement. “Instead of releasing the hostages in an agreement and ending the war, the Israeli government is sending more soldiers to Gaza, to fight in the same places they’ve fought time and again.”

For some on the right, the announcement of the new offensive may offer a suggestion that Israel intends to conquer and hold additional land in Gaza for potential non-military purposes. Since the beginning of the war with Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023, attack, the Israeli far right has called on Israel to occupy the territory and reestablish settlements that were evacuated two decades ago. The Israeli government has repeatedly ruled out resettling the enclave.

International officials are also Israel’s military renewed campaign. Volker Türk, the U.N. human rights chief, said in a statement that Israel had attacked aid workers. U.N. officials described a “mass grave” that contained the remains of 15 aid workers from the Palestine Red Crescent Society, the United Nations and Palestinian civil defense, a Gaza governmental body. One more aid worker’s body is still missing.

“I condemn the attack by the Israeli army on a medical and emergency convoy on 23 March resulting in the killing of 15 medical personnel and humanitarian workers in Gaza,” Türk said. “The subsequent discovery of their bodies eight days later in Rafah, buried near their clearly marked destroyed vehicles, is deeply disturbing.”

The United Nations says hundreds of aid workers have been killed in the war. In one incident last year that drew broad attention, Israel apologized for what it said was an unintentional strike that killed seven workers for World Central Kitchen.

Israel is contesting this week’s allegations, saying that the vehicles had advanced “suspiciously” toward IDF troops without prior coordination and that Hamas operatives were among the bodies recovered.

“It’s truly not surprising that terrorists are once again exploiting medical facilities and equipment for their activities,” said IDF spokesperson Nadav Shoshani on X. “When terrorists act in an active combat zone, we will do whatever it takes to protect our civilians and troops.”

Asked about whether the U.S. Department of State would investigate, a spokesperson said at a press briefing on Monday, “The use of civilians or civilian objects to shield or impede military operations is itself a violation of international humanitarian law, and of course we expect all parties on the ground to comply with international humanitarian law.”

On Wednesday, fighting was ongoing. Evacuation orders had already been issued by the time of Katz’s announcement, and Palestinian radio reported that the area around Rafah, in southern Gaza, had almost emptied, according to Reuters.

I help tell Jewish women’s stories. Trump’s attacks on diversity are an assault on everyone’s history.

History is powerful, and there’s no better evidence than the attempt to erase it.

As a historian and as CEO of the Jewish Women’s Archive, I’ve staked my career on a theory of change that insists that the stories we tell about the past and the present determine our futures. That’s why I am alarmed — but not surprised — that the Trump administration has made it a priority to wipe mentions of women, transpeople and people of color from sites that celebrate their contributions to American history and society.

In an executive order, Donald Trump says he is “restoring truth and sanity to American history” by cracking down on the Smithsonian and other institutions that have sought to complicate and diversify the stories they tell in recent years.

It’s clear to me that doing so is a key element of Donald Trump’s strategy to undermine the resources Americans have to resist his policies, for when we are deprived of a history that reflects the diverse leaders who made change in the past, our capacity to make change today is diminished.

Of course, the contributions of women and other marginalized people can’t be erased from history with an executive order prohibiting certain words or terms. It’s an absurd notion, the delusion of a narcissist convinced of his own absolute power to determine reality. But it is nevertheless an act of violence, one that works hand in hand with the sowing of disinformation that is Trump’s trademark and the undermining of expertise that drives the work of DOGE.

One of the many lessons history teaches us is that when people’s stories are obliterated, their rights are not far behind. It is instructive, resonant, and, frankly, terrifying, to recall that the first Nazi book burning took place in 1933 at the Institute of Sexual Science in Berlin, founded by the Jewish LGBTQ pioneer Magnus Hirshfeld. Or that Emma Goldman’s magazine, Mother Earth, was banned two years before her U.S. citizenship was revoked and she was deported.

Those who fight for survival understand implicitly that their stories are a key tool of resistance. This understanding is why Miriam Novitch smuggled underground publications in Occupied France during World War II and devoted her later years to collecting testimonies and artwork for the Ghetto Fighters’ House collection. It is why South African Fanny Klenerman ran a bookshop to foster anti-apartheid activism. It is why civil rights activists in the United States, including many Jews like Vicki Gabriner, created Freedom Schools in American communities in the South.

I wrote this in the waning days of Women’s History Month 2025. While focusing on a marginalized group for one month doesn’t correct history’s incompleteness, ideally it makes us more attuned to the absences in our narratives during the rest of the year and helps us notice other voices that are missing. Hearing others’ stories helps us build empathy and recognize our common humanity. It is a much-needed bulwark against polarization and distrust. This is how movements like feminism have inspired further liberation beyond their initial focus.

My own work at JWA is not changing now that the calendar has turned to April, but many institutions will no doubt relax their efforts to highlight women’s stories and lift up their voices. This year, it’s more urgent than ever that we take the message of Women’s History Month to heart and redouble our commitment to documenting and amplifying the stories that are being erased. It’s actually simple: Seek out and highlight the stories of those groups who are being erased. Notice who you’re quoting, inviting to speak, talking about, and hiring, and center those who are being sidelined elsewhere. We make choices every day about which voices to amplify. Be intentional in your choices.

Above all, don’t forget that we are all history makers. Together we have the power to create a different story than the one unfolding around us today.