Graham Platner, populist progressive running for Senate in Maine, reveals Nazi tattoo on his chest

An oyster farmer and progressive military veteran running an insurgent campaign for Maine’s Democratic Senate nomination admitted this week to having had a Nazi tattoo for nearly two decades.

Graham Platner shared video of himself shirtless, sporting the tattoo, on a popular progressive podcast. He denied that he himself ever held Nazi views, instead claiming he had gotten the tattoo while “inebriated” as a young adult without knowing what it meant.

Since launching his campaign this summer, the 41-year-old Platner had picked up steam in left-wing circles for his populist positions, including calling Israel’s military campaign in Gaza a genocide. The political neophyte has won endorsements from progressive leaders including Vermont’s Sen. Bernie Sanders, who is Jewish. Morris Katz, the Jewish campaign strategist behind Zohran Mamdani’s digital ads for New York City mayor, made a campaign launch video for Platner.

As of Sept. 30, according to campaign finance records, Platner led his Democratic rivals in campaign donations with $3.2 million in contributions. At his rallies, the biggest applause comes when he delivers lines like “Our tax dollars can build schools and hospitals in America, not bombs that destroy schools and hospitals in Gaza.”

But scandal has started to plague Platner’s campaign in recent days after his past posts on the web forum Reddit came to light. In those posts, Platner made comments about why Black people don’t tip, derided rural white Americans and declared himself a Communist.

This week, a recent video of a shirtless Platner also surfaced in which he can be seen sporting a chest tattoo of a Totenkopf, a Nazi-era skull-and-crossbones design favored by SS officers. “Totenkopf,” or “Death’s Head,” was also the name of the division of officers who guarded the concentration camps.

The source of the video was Platner himself, who shared it on an episode of “Pod Save America” on Monday.

The Jewish Community Alliance of Southern Maine, the state’s largest Jewish body, said in a statement that it was concerned about the tattoo as well as other aspects of Platner’s campaign.

“This tattoo appears to be a ‘death’s head’ symbol used by the SS, the organization most responsible for the genocidal murder of 6 million Jews and millions of other victims during WWII,” Zach Schwartz, director of the Portland-based group’s Jewish Community Relations Council, said in a statement to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “We hope that Mr. Platner would condemn, in no uncertain terms, the meaning behind this tattoo and everything it stands for.”

Schwartz added that Platner’s “broader messaging” also troubled them, in particular his pledge not to take money from the pro-Israel lobby AIPAC.

“Maine’s Jewish community is not a monolith, nor does every Jewish Mainer support AIPAC. However, Platner’s repeated, singular focus on not taking money from AIPAC plays into familiar, harmful tropes that Jews or organizations like AIPAC control the government,” the statement read. (An increasing number of Democratic candidates including Massachusetts Rep. Seth Moulton, a centrist running for his state’s Senate primary, have also pledged not to accept money from AIPAC.)

On “Pod Save America,” Platner said he had gotten the tattoo in Croatia in 2007, while on shore leave from a tour of duty in Iraq, without knowing what it stood for.

“We went ashore in Split, Croatia, myself and a few of the other machine gun squad leaders. And we got very inebriated, and we did what Marines on liberty do, and we decided to go get a tattoo,” Platner told the show’s host Tommy Vietor.

He said he and his companions “chose a terrifying-looking skull and crossbones off the wall because we were Marines, and skull-and-crossbones are a pretty standard military thing. And we got those tattoos and then we actually all moved on with our lives.”

“I am not a secret Nazi,” Platner said elsewhere in the interview, adding that he had passed a full security clearance in 2018 to work as a State Department contractor. “If you read through my Reddit comments, I think you can pretty much figure out where I stand on Nazism and antisemitism and racism in general. I would say a lifelong opponent.”

Platner did not address why he still has the tattoo. He has said he intends to stay in the race. He also claimed not to have known the symbol had Nazi connotations until getting wind of opposition research against him during his current Senate campaign.

However, quoting an anonymous former acquaintance of his, Jewish Insider reported on Tuesday that Platner had referred to the ink as “my Totenkopf” more than a decade ago and would frequently take his shirt off at the Washington, D.C., bar where he worked at the time. “He said it in a cutesy little way,” the source said. Jewish Insider additionally reported that Platner had met with other men with Nazi links, including one neo-Nazi who is running for a seat on Bangor City Council.

Platner’s political director, former state Senator Genevieve McDonald, resigned from his campaign last week following the reveal of his Reddit posts. On Facebook days after her resignation, McDonald also took Platner to task for his tattoo.

“Graham has an anti-Semitic tattoo on his chest,” McDonald wrote, according to screenshots of the post on social media. “He’s not an idiot, he’s a military history buff. Maybe he didn’t know it when he got it, but he got it years ago and he should have had it covered up because he knows damn well what it means. His campaign released it themselves to some podcast bros, along with a video of him shirtless and drunk at a wedding to try to get ahead of it.”

While some in the online left denounced Platner over the tattoo and rebuked previous support for him, he has kept some defenders. Lyle Jeremy Rubin, a Jewish military veteran, author and left-wing commentator, is one of them.

“Every other marine I knew had some version of the same tat. Please,” Rubin wrote on BlueSky, adding in a separate post, “This is a great example of what happens when the Democratic Party is defined by goody two-shoe losers who have lived their entire lives among fellow goody two-shoe losers.”

The Senate race against Republican incumbent Susan Collins is currently considered a tossup and will be one of next year’s most closely watched elections.

Jewish fears about Zohran Mamdani reveal more about us than about him — and it’s a problem

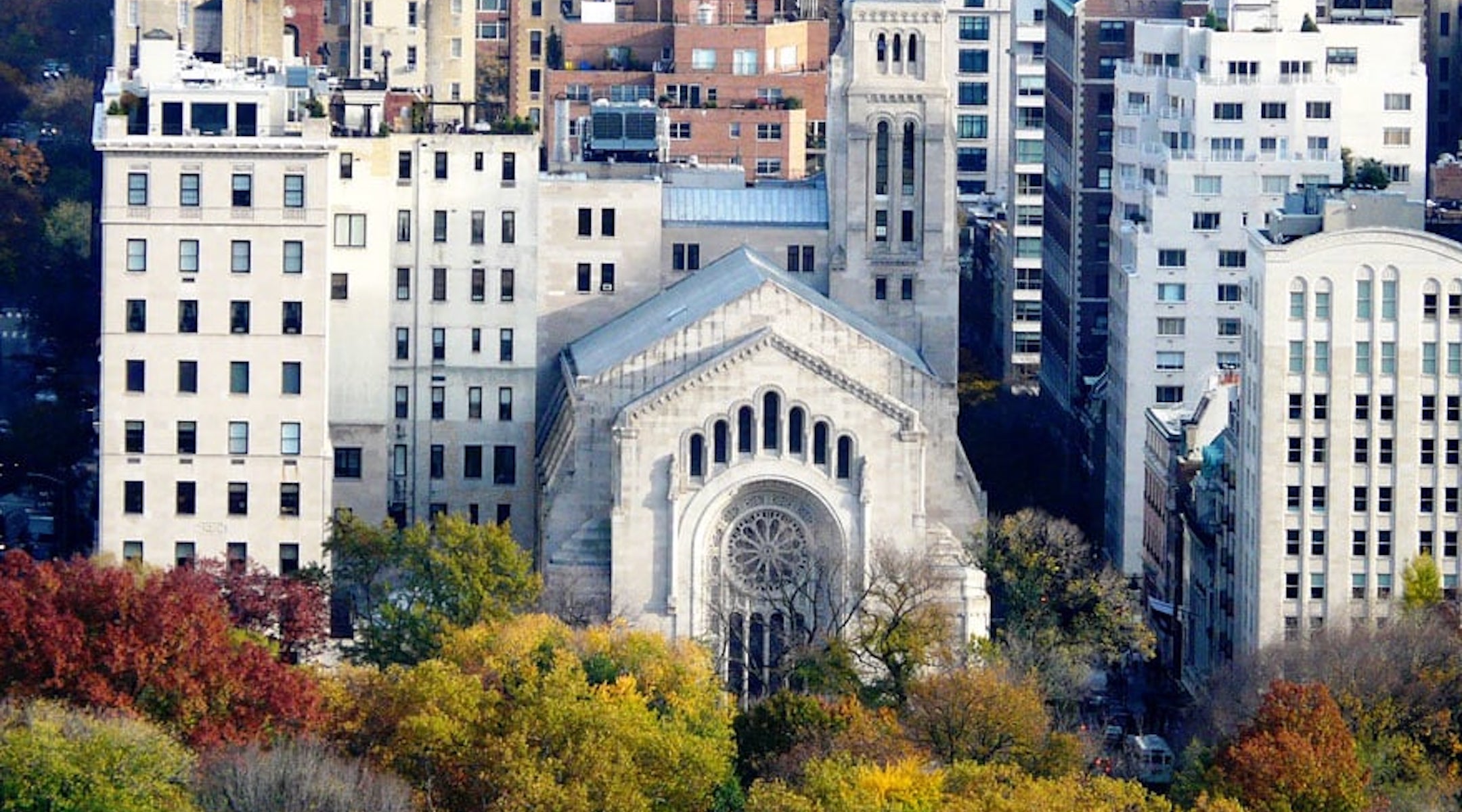

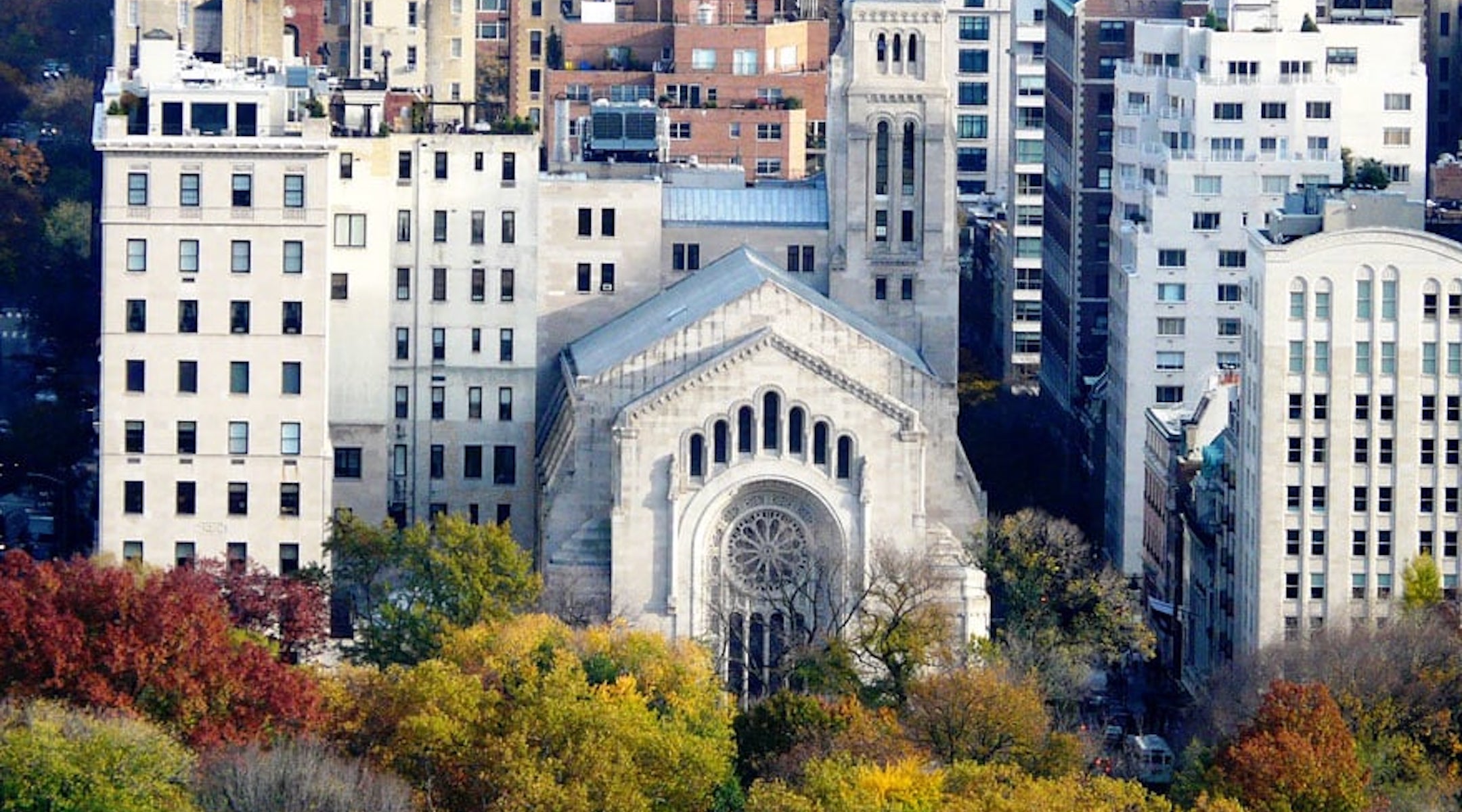

On the surface, I have a lot in common with Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove. We have 138 mutual friends on Facebook. We are roughly the same age. And the synagogue he has led for the past quarter century, Park Avenue Synagogue, is where I attended Hebrew school as a teenager in the early 90s, learning with some of the city’s best teachers.

And yet when I saw Cosgrove’s jeremiad against Zohran Mamdani, the Democratic Party nominee for mayor of New York, I couldn’t find much overlap at all. So as his sermon makes the rounds, I decided to share my perspective as a New Yorker with decades of experience engaging Jewish voters.

While Cosgrove was finishing high school in Los Angeles, David Dinkins was elected mayor of New York. He had a long record of alignment with Jewish institutions regarding Israel. Dinkins opposed anti-Zionist resolutions at the United Nations. He traveled to Israel three times, including during the Gulf War while mayor.

I remember in 1990, South African anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela had been released from prison and was planning to visit New York City. Dinkins, who like most New Yorkers considered Mandela a hero, was thrilled to welcome him. The Jewish communal leadership, on the other hand, had mixed feelings. See, Mandela saw parallels between the Palestinian struggle and his own, and was an ally of Yasser Arafat. Therefore, Mandela was tainted.

Dinkins served just a single term as mayor. Despite putting the city on a path towards greater safety, he faced significant challenges (including the Crown Heights riot) and was replaced by notorious bully — and future Trump attorney — Rudy Giuliani. Jewish voters may have been the difference in denying Dinkins a second term (and the great Ruth Messinger a first!).

David Dinkins was the first non-white person to serve as mayor of New York. Today, Zohran Mamdani is seeking to be the city’s first Muslim mayor. He is supported by many Jews, possibly more than any other candidate, including thousands of members of Jews for Racial and Economic Justice, an organization founded when it organized a Shabbat service at B’nai Jeshurun to welcome Mandela to New York back in 1990.

Read another perspective: “We need a ‘Great Schlep’ from Park Avenue to Park Slope to turn out Jews against Zohran Mamdani“

I was born in New York City and have lived here most of my life. Every single mayor in my lifetime has supported Israel, regardless of its actions in the West Bank and Gaza. None has supported Palestine.

To put it another way: Palestinian New Yorkers have never had a mayor who they would consider an ally when it comes to issues impacting their homeland. Many mayors have been happy to fete Israel’s worst leaders. Today, the main challenger to Mamdani, Andrew Cuomo, joined Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s legal defense team. Cosgrove said Jews will be unsafe if Mamdani is mayor. Will Palestinians in New York City be unsafe if Cuomo is elected?

Remember during the Democratic primary debate, when the candidates were asked which country they would visit first if elected mayor? Many, including Cuomo, said Israel. But Mamdani didn’t say he’d visit Palestine; he said he’d stay here and focus on his actual job: running New York City.

Mamdani has never said anything to suggest he would withhold protection from Jews; on the contrary, he has repeated his commitment to their safety. Mamdani’s love for New York and New Yorkers is impossible to miss; he is running a campaign driven by the belief that this great city should be available to all. Contrast that with his suburban nepo rival, who is trying to fearmonger his way into office.

In his sermon, Cosgrove suggests that Jews need to prioritize the safety of other Jews over non-Jews, to prioritize the safety of Israeli Jews over Palestinians. He suggests that this is natural, an act of self-interest common to all communities. He said, “For Jews, ahavat yisrael, love of Israel, does take precedence over other loves. Every human being is created with equal and infinite dignity, yet we prioritize the needs of our families, our people, and our nation.”

Maybe this is why Cosgrove and so many others struggle to understand how Mamdani, as a Muslim anti-Zionist, could ever care as much about Jewish New Yorkers as Muslim New Yorkers. They have projected their own value system onto him, and don’t trust him to act on behalf of those outside his own group. (Or maybe they don’t realize that for true New Yorkers, the outgroup is New Jerseyans.)

In 2008, I was the co-creator of The Great Schlep, the campaign Cosgrove mentioned in his sermon, where young Obama supporters convinced their skeptical grandparents to vote for the first Black president. He thinks we need one in reverse, with the wise elders of the Upper East Side schooling the wild youth of Brooklyn. But in fact, despite their distinct views about Israel, the dynamics that made older Jewish Democrats initially skeptical of Obama are the same that make you and your congregants skeptical of Mamdani. It’s fear, stoked by Israeli hasbara, amplified by right-wing media, and seasoned with a pinch (or more) of old-fashioned bigotry.

The good news is that, whether or not Cosgrove or his congregants vote for him, I believe Mamdani will not turn his back on them. Unlike Trump, or Giuliani, or Cuomo, he doesn’t subscribe to the Roy Cohn model of politics. He actually takes the notion of being a public servant seriously. I hope we are all lucky enough to experience it.

We need a ‘Great Schlep’ from Park Avenue to Park Slope to turn out Jews against Zohran Mamdani

This piece is adapted from a sermon delivered on Oct. 18, 2025. It can be viewed here.

On Shabbat, I told my congregants something I believe strongly: that Zohran Mamdani poses a danger to the security of New York’s Jewish community.

Mamdani’s refusal to condemn inciteful slogans like “globalize the intifada,” his denial of Israel’s legitimacy as a Jewish state, his call to arrest Israel’s prime minister should he enter New York, and his thrice-repeated accusation of genocide in last week’s debate — for these and so many other statements, past, present, and unrepentant — he is a danger to the Jewish body politic of New York.

Zionism, Israel, Jewish self-determination — these are not political preferences or partisan talking points. They are constituent building blocks and inseparable strands of my Jewish identity. To accept me as a Jew but to ask me to check my concern for the people and State of Israel at the door is as nonsensical a proposition as it is offensive — no different than asking me to reject God, Torah, mitzvot, or any other pillar of my faith.

One need look no further than the events of the past week (or, for that matter, the past two years) to understand the shape and substance of the Jewish soul — how bound up we have all been with the plight of the hostages and our jubilation at their release. In our highs and in our lows, in our tortured angst and our fragile hopes, in our prayers and our protests, we feel our connection to Israel and its people. It is the invisible string that has tugged at our hearts since the very beginnings of our people.

Mamdani’s distinction between accepting Jews and denying a Jewish state is not merely rhetorical sleight of hand or political naivete, though it is, to be clear, both of those things. His doing so is to traffic in the most dangerous of tropes, an anti-Zionist rhetoric that, as we have seen time and again — in Washington, in Colorado, in ways both small and large, online and in person — has given rise to deadly antisemitic violence. This past summer, you may recall, at the Glastonbury Music Festival in England, the crowd erupted into chants of “Death to the IDF.” Where exactly would a Mamdani administration stand should that happen next summer in a concert on Governors Island, or in Central Park? I am not one to play the politics of fear. The entire thesis of my career is to play offense, not defense. But right now, I am throwing a flag on the field and calling out a threat to the Jewish people five minutes early rather than risk being five minutes too late.

For me, the breaking point came not with Mamdani’s earlier statements, his accusations of Israeli genocide, his refusal to name Hamas a terrorist organization, or, for that matter, the flimsiness of his experience, policies, and associations. For me, the damning moment came in a statement he made to a Brooklyn synagogue last week, when he sought to assure that community, as reported in the press, that his views on Israel would not amount to a litmus test for service in his administration. “I am not a Zionist,” he said. “I’m also not looking to create a city hall or a city in my image. I’m going to have people in my administration who are Zionists — whether liberal Zionists, or wherever they may be on that spectrum.”

And while one could commend Mamdani for focusing on professional qualifications rather than political inclinations, for me, the comment was a most unsettling tell. The comment was a most unsettling tell. When Mamdani says “Zionists are welcome” in his administration, he may think he’s offering reassurance, but in fact he reveals something darker — the assumption that Jewish self-determination is an ideology to be tolerated, rather than a birthright to be respected. The very need to say it betrays a bias so deeply held that it should make us shudder.

Read another perspective: “Jewish fears about Zohran Mamdani reveal more about us than about him — and it’s a problem“

Some believe it unwise to raise alarms given the likelihood of Mamdani’s election. Better to hold our tongue in anticipation of the need to work with him. I hear the concern and understand the pragmatism. I choose principle instead.

A vote for Mamdani is a vote counter to Jewish interests. A vote for Curtis Sliwa, whatever his merits, is a vote for Mamdani. There is a path to victory — i.e., Andrew Cuomo — but it means every eligible voter must vote. In the last election, somewhere between 15-20% of eligible voters turned out; we must do better. Nobody can sit this election out.

And yet, as good as it feels to speak my mind — and important as it is to do so — the truth is, doing so neither moves the electoral needle sufficiently nor addresses my deeper concern in this mayoral race.

How so? First, in my synagogue, I am preaching mostly, if not entirely, to the converted. I had my congregants at hello. For me to name the dangers of an anti-Zionist mayoral candidate in this community is a declaration so self-evident that not only does it risk being cliché, but it could serve to feed the very intersectional politics that have fueled Mamdani’s campaign in the first place.

Hopefully my words will prompt my congregants and their network of likeminded voters to turn out in this election, and that is not nothing. But all of my congregants — and there are a lot of them — who have emailed me, called me, and texted me urging me to go scorched earth on Mamdani, to invite Andrew Cuomo to address our community, all fail to understand that it is not the Park Avenue Synagogue community that needs convincing but the Korean, African-American and Latino communities of New York. We must turn out the vote, but if it is a win that you want, Cuomo needs to speak at more churches and fewer synagogues, more barbershops and fewer boardrooms, up his online game, and meet New Yorkers where they are. If it is a win you want, I’d encourage Jewish New Yorkers to redirect their angst from their rabbis who already believe what they believe and instead direct it to the issues, places, and people where the needle needs to be moved and can be moved.

Because my real concern is the painful truth that Mamdani’s anti-Zionist rhetoric not only appeals to his base but seems to come with no downside. What business does an American mayoral candidate have weighing in on foreign policy unless it scores points at the ballot box? I don’t doubt that Mamdani’s anti-Zionism is heartfelt and sincere, but its instrumentalization as an election talking point should frighten you in that it says more about the sensibilities of our fellow New Yorkers than it does about Mamdani himself. And the fact that the latest polls suggest that the Jewish community of New York is almost evenly split between Mamdani and Cuomo further names the problem to be not just one of our fellow New Yorkers, but our fellow Jews.

Which means that if there is a play to be made here, given the limitations of time, resources, and people, our efforts should be directed to where we have influence and where the needle can be moved. Those in the middle — the undecided, the proudly Jewish yet unabashedly progressive, the affordability-anxious, Netanyahu-weary, Brooklyn-dwelling, and social-media-influenced — who need to be engaged. In other words, other Jews. Jews who may not be you, but may be your friends, may be your children, and may be your grandchildren.

It is these Jews, our friends and our family, who need to be persuaded to prioritize their Jewish selves. I am imagining an informal campaign, reminiscent of what the comedian Sarah Silverman organized in 2015, when she called on young Jews to go to Florida to persuade their Bubbies and Zaydes to vote for then-Sen. Barack Obama. It was called “The Great Schlep.” Now, 10 years later, in 2025, we need a Great Schlep in reverse. Not from the Upper West Side to Surfside, but from Park Avenue to Park Slope, to remind the ambivalent and undecided that Jewish identity is not a partisan position but a sacred inheritance always in need of defense — especially today.

Who are these Jews about whom I speak? First, in many cases, they have grown up with an Israeli prime minister with whom they not only do not identify, but who represents the very antithesis of every other liberal Jewish value they hold dear. They don’t want anything to do with Netanyahu or the vision of Israel that he and his government represent. For them, Mamdani’s rejection of Israel may be a difference, but it is one of degree, not in kind. Second, these Jews feel strongly that they are not voting for the “Mayor of Jerusalem” and therefore local issues preempt everything else — like finding a job and living well in the city in which they were born without having to spend 50% of their monthly paycheck on rent. Third, the Cuomo you see as a commonsense experienced candidate – who, like any politician, comes with both personal and professional baggage — they see as an exemplar of the same-old, same-old tired politics in desperate need of being rejected.

For a Jew who wants to live a frictionless Jewish existence and return to a pre-Oct.-7 world when being a Jew was a nonevent, it is more appealing to vote for the candidate believed able to do the greatest good for greatest number of New Yorkers, no matter how preposterous some of his proposals are, even if that candidate lacks the credentials to run my fantasy football league, never mind the most complicated city in America.

So, when you talk to your friend, colleague or family member, under no circumstances roll your eyes or wag your finger. One should not do so because such an approach is sure to backfire, but, more importantly, because to do so delegitimizes the altogether legitimate feelings that person holds.

And when you do share your views, if it were me, I would begin the conversation by talking about love. How love — be it of another person, of family, or of country — never exists in a vacuum. How it evolves, it changes, it challenges. How the meaning of love comes not in the black-and-white cases — of love without question, or when there is no love at all — but in the gray areas — when love is tested. It is then — in those moments when we measure and re-measure, when the conditions of our love are challenged — that we find out who we really are, and discover what love is all about.

I would share with that other person that love is a commodity that neither is endless nor can be distributed equally. To be a Jew, to be anything for that matter, means to prioritize one love over another. The math is not precise; love cannot actually be measured in bushels and pecks. Concerned as we are with the well-being of humanity, we simply cannot nor should be expected to care for every human the same way. To paraphrase the moral philosopher Bernard Williams: A man who sees two people drowning, his wife and a stranger, and pauses to consider which one maximizes the public good, is a man who has had “one thought too many.”

Self-preservation and self-interest are not only legitimate, but essential to sustaining an ethical life. It is why, when the rabbinic sage Hillel was asked by a would-be convert to distill all of Jewish teaching into a single sentence, he did not quote the Golden Rule, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Rather Hillel said, “What is hateful to you, do not do to another.” One cannot love another as yourself, argued Hillel and Jews throughout the ages. The best we can do is to love another because they are like us, created alike in God’s image. There are limits to love. There is a place for self-concern.

And for Jews, ahavat yisrael, love of Israel, does take precedence over other loves. Every human being is created with equal and infinite dignity, yet we prioritize the needs of our families, our people, and our nation. This week we began reading the book of Genesis, the most universal story of all — not the creation of the first Jew, but the first human being. Universal as the story is, the 11th-century commentator Rashi immediately reads it as a justification for the Jewish claim to the land. In the 11th century, Rashi’s comment served as a defense against the Crusader-era argument that Jews have no claim to Israel. In our day, Rashi’s comment can be read as a reminder to progressive Jews of the legitimacy of the Jewish claim to the land. You can love Israel without loving all Israelis. You can love Israel without loving its government. In this moment when the Jewish connection to Israel sits precariously at the intersection of identity politics and rising antisemitic violence, it is not only allowable to place the Jewish body politic at the forefront of our concern; it is required of us.

Some will argue that disqualifying Mamdani because of his anti-Zionist posture only feeds the antisemite’s charge of dual loyalty. I hear this objection and respect those who say it, and I fully reject the argument. I reject it first because it surrenders to a Jewish insecurity and fear about what the antisemites might think. I don’t care what the antisemite thinks, and neither should you. And second, I reject it because it betrays a category error with regard to the place Israel has in my Jewish being. Israel is not a detachable policy preference; it is integral to my Jewish identity. To delegitimize Israel, as Mamdani has repeatedly done, is an attack on my personhood as a Jew, as an American, and as an American Jew. This is not about dual loyalty; this is about my fundamental security and the security of my co-religionists.

And lest you think I don’t understand, be assured that I do. I understand that it is not easy. It is hard to prioritize love of Israel when the government of Israel does not reflect your sensibility — that feeling of your love being tested. I understand that it is hard to prioritize one’s Jewish self over the array of other identity labels we wear. I understand that it is hard to reach beyond the sparkle of the shiny new object in favor of the one that is scuffed, worn, and familiar.

I wish it were otherwise. I wish we had two candidates with equal interest, or better yet, equal disinterest in the Jewish community. I would love nothing more than our mayoral contest to be focused solely on affordability, food instability, education, policing, sanitation, taxes — the everyday issues that shape our great city’s life. A contest where all of you could argue to your heart’s delight about which policies best serve the future of our great city, and I could give sermons on, well, anything else. But this election cycle, that is simply not the case. We can only play the cards we are dealt. And in this hand, I choose to play the one that safeguards the Jewish people, protects our community, and ensures that our seat at the table remains secure. I choose steadiness over spectacle, tested loyalty over reckless gamble.

It’s a story as old as the Bible itself. We stand in the Garden — staring at that Big Apple — wondering what is in our long-term best interest. The options are before us. We are wrestling within and with each other and we know we have to make a choice.

Let us choose wisely: To engage, mobilize, turn conviction into action, self-concern into ballots and most of all — vote. Now is the time to make our voices heard.

Federal judge allows Northwestern to block enrollment for students who boycotted antisemitism training

A federal judge in Chicago allowed Northwestern University to discipline students who refused to watch an antisemitism training video.

Judge Georgia Alexakis declined Monday to issue a restraining order in a lawsuit filed by Northwestern Graduate Workers for Palestine and two graduate students. The plaintiffs claimed that an antisemitism training required by the school for enrollment was biased and discriminatory toward Palestinian and Arab students.

“Northwestern University’s Training is not intended to foster a civil and collaborative workplace or remedy discrimination but rather is aimed at suppressing political anti-Zionist speech and speech critical of Israel,” the complaint read.

The “Antisemitism Here/Now” training video, produced by the Jewish United Fund of Chicago, the city’s Jewish federation, did not ask students to agree with its contents. Fewer than three dozen students declined to watch it in protest.

Attorneys for Northwestern said that 16 students currently face enrollment holds for failing to watch the training, though they added that they were unsure if all students affected did so out of protest.

In her ruling, Alexakis acknowledged that the graduate students affected by the holds face “irreparable harm,” but said that the student’s lawyers had failed to prove Northwestern had a discriminatory motive in requiring the video.

“Because the plaintiffs have failed to meet their burden in this threshold inquiry, we do not move on to conduct a balancing of the harms,” Alexakis said in her ruling, according to the school’s student newspaper, The Daily Northwestern. “For that reason, I have to deny the motion.”

The complaint also criticized the school for adopting the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s definition of antisemitism, which the complaint said “effectively limits Arab students, and particularly Palestinian students, in their expressions of nationalist aspirations and protest against mistreatment of their ethnic group.”

The antisemitism training was announced by Northwestern in March in an email to the student body that cited President Donald Trump’s Jan. 29 executive order, “Additional Measures to Combat Anti-Semitism.”

“The truth is that Northwestern’s antisemitism training discriminates against Jewish students who are anti-Zionist, against Palestinian students, and against all people of good conscience, and it has nothing to do with Jewish safety,” said Jonah Rubin, the manager for campus organizing for Jewish Voice for Peace, at a press conference. “It’s about Northwestern trying to cozy up to an increasingly authoritarian administration.”

On Friday, the rabbi circles Manhattan — now with tech support to protect an essential Shabbat tool

Around 6:15 a.m. on a recent Thursday, Rabbi Moshe Tauber parked his van in the merge lane of the Henry Hudson Parkway at 72nd Street. He turned on his hazard lights and ran out of the vehicle with a flashlight. His wife, Chaya, sitting in the passenger seat, watched anxiously.

Tauber, 51, turned his head upward, shined his flashlight on the nylon fishing wire strung up 30 feet from the ground between two poles, and ran back to the car. All clear — the boundary was unbroken.

For the past 25 years, this process has been the rabbi’s routine on both Thursday and Friday mornings: leaving his home in Monsey, an Orthodox enclave in Rockland County, hours before sunrise in order to circumnavigate the entire island of Manhattan. His mission: to check every part of the borough’s eruv — the symbolic boundary, marked by strings and other man-made and natural elements, inside of which observant Jews may carry objects like food, keys and even babies on Shabbat and certain holidays.

Maintaining the eruv, which must be unbroken to be considered kosher, has been Tauber’s job since 1999. Tauber says it doesn’t make sense for someone else to sub in for him, simply because he knows the eruv so well and can do it so efficiently, after having inspected it for so many years. With Chaya’s approval, he even missed the early-morning birth of his 13th and youngest child, now 7, to check the eruv on a Friday morning. He immediately went to the hospital to visit mother and baby after his inspection was done.

“I don’t know if I can explain what I like in this job,” Tauber said. “I like it.”

Now, for the first time, the eruv inspector is getting some high-tech assistance.

Installed in August, a new sensor system created by technology entrepreneur Jerry Kestenbaum — also the creator of the residential building software company BuildingLink — magnetically snaps onto multiple locations of the eruv. The 142 sensors detect changes in the angle of the wire and send a signal to a receiver held by Spectrum on Broadway, the lighting and electrical company responsible for maintaining the line per Tauber’s instructions. The sensors themselves are battery-operated and meant to last for six to 10 years, sealed in a waterproof case.

“It gives me more comfortability,” Tauber said. But he’s not planning on ceding oversight entirely to the machines, saying, “I know I need to check because the sensors are not 100%.”

The sensors mark the first major innovation to Manhattan’s biggest eruv, installed in 1999 after Adam Mintz, then the rabbi of Lincoln Square Synagogue, requested its installation to surround his Upper West Side neighborhood. (Prior to the borough-wide eruv, different parts of the city each had their own, but travel between them while carrying anything was prohibited on Shabbat.)

According to Jewish law related to Shabbat, no items can be carried outside the home on what is supposed to be a day of rest and prayer. Recognizing this as a potential burden, rabbis in the Talmudic era devised a workaround: The boundary defined by the eruv would extend the “private” zone where carrying is permitted. Despite some community objections — sometimes from Jews and non-Jews who worry that the eruv will change the “character” of their neighborhoods, or civil libertarians who worry about the blurring of church and state — nearly every observant community, from big cities to small towns, is surrounded by an eruv.

The Lincoln Square eruv has expanded multiple times since 1999, now encompassing most of Manhattan, from 145th Street between Riverside Drive and Malcolm X Boulevard at its northernmost point, roughly down FDR Drive all the way to the bottom of Manhattan at the South Street Ferry, and back up the Henry Hudson Parkway.

In the years since he became its inspector, Tauber’s dedication to the eruv has been unflagging. He made sure it was unbroken after 9/11 (it didn’t extend all the way downtown at the time), after the 2003 citywide blackout, after Hurricane Sandy in 2012 and throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. In Tauber’s 25 years of inspections, the eruv has only been down once over a Shabbat, during a snowstorm in 2010.

In addition to checking the eruv twice a week, Tauber helps his wife run a daycare, and he teaches boys at a yeshiva. He hasn’t taken a vacation longer than a few days for a quarter century.

Chaya Tauber said she has a theory about why he likes the eruv job so much. “[It’s] many hours of a busy week — he has more jobs, it’s not the only job — that he can be by himself,” she said.” Quiet time. I think he likes the traveling, also.”

Just two weeks ago, he helped establish an eruv around Columbia University Medical Center in Washington Heights and the surrounding apartments. Eventually, the plan is to connect it to the main Manhattan eruv — and potentially to other smaller eruvs in Upper Manhattan. There, smaller eruvs serve portions of Washington Heights with many observant Jews, including one that is home to the Orthodox flagship Yeshiva University.

Newly added motion sensors, encased in plastic, are clipped onto a part of the eruv wire near the Manhattan Bridge. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

Kestenbaum, whose new business, Aware Buildings, provides sensors for home security, said the idea for the electronic eruv technology came about during a conversation with Mintz, now the rabbinic leader of Kehilat Rayim Ahuvim (The Shtiebel) on the Upper West Side at the Marlene Meyerson JCC.

“I was saying to him that the sensors can be applied to many, many things that we’re used to doing manually,” said Kestenbaum, whose wife converted to Judaism under Mintz’s supervision.

“It’s a complicated eruv where the deployed environment changes,” Kestenbaum explained. “It’s not [like] in the suburbs, where the outline of the eruvs remains constant. Things go wrong. You’ve got scaffolding that gets put up. You’ve got other things that happen. The weekly eruv job is not just fixing, sometimes it’s rerouting.”

The complications are what gets Tauber out the door around 3:30 a.m. on inspection days. Not only does he beat rush hour, but once the sun begins to come up, it’s far more difficult to see the wire.

Now, the sensors can help him locate the wires more easily — and safely. “I used to walk [out of the car] because I couldn’t see it without the sensors,” Tauber said, pointing to a section near the Manhattan Bridge. “See the sensors? You don’t have to see the actual line.”

Tauber has been surprised by the willingness of various city agencies and construction crews to accommodate him in his unusual line of work.

“Even though we are Jewish, and we know we are not the most liked people here, but I never, ever had a problem with any organization or department officials, or even a construction company — they always come across,” he said. “They always look like they admire something which is religious.”

For Chaya Tauber, the early mornings and constrained vacations are worth it because of the way her husband’s work allows Manhattan Jews to observe one major law of Shabbat with ease.

“There is so much less desecration of Shabbos,” Chaya Tauber said, adding that when the eruv is up, “at least they’re not transgressing on this particular halacha. That makes this job such a responsibility.”

She converted during the pandemic. Israeli immigration officials say her Zoom course doesn’t count

When Isabella Vinci stepped out of the mikvah on Nov. 11, 2021, she thought she had done everything that would be required to become Jewish. A beit din, or rabbinic court, had approved her conversion after nearly a year of study with Rabbi Andrue Kahn at Temple Emanu-El, a Reform congregation in New York, including a congregational course and one-on-one meetings.

Within a year, she visited Israel on Birthright and returned on an immersion program to teach English in an Orthodox public school in Netanya. Friends, rabbis and colleagues, she said, embraced her as Jewish.

Israel’s Population and Immigration Authority did not.

In a pair of decisions issued in January and again last month, immigration officials rejected Vinci’s application for aliyah under the Law of Return and then denied her administrative appeal.

The letters point to two main problems: She studied for conversion online during the COVID period, and she did not prove sufficient post-conversion participation in a synagogue community — particularly while living in Israel.

Vinci, 31, had to leave behind the life she had built in Tel Aviv and move back to the United States. She is now preparing a court petition with the Israel Religious Action Center, the legal‐advocacy arm of Reform Judaism in Israel.

For decades, IRAC and other non-Orthodox advocacy groups have complained about attempts by religious parties in Israel to block the recognition of conversions outside of Orthodoxy. But Vinci’s advocates say she was blocked from citizenship despite a Supreme Court ruling from 2005 allowing overseas conversions, regardless of denomination.

Her rejection also reflects a gap between the Diaspora and Israel, they say, in everything from religious practice to the adaptations made necessary by the pandemic.

“The whole world — from rabbis to strangers who hear my story — tells me I am Jewish. They see that I am putting everything on the line to be a part of our people. The only ones telling me that I’m not Jewish are within this government agency,” Vinci said in an interview, describing months of silence and what she felt was the government’s unwillingness to consider new supporting documents. “Why aren’t they putting in the work and the effort to actually understand where I’m coming from?”

Vinci grew up Catholic in a sprawling, multicultural family, spending early years in Florida and most of her childhood in Omaha, Neb. She never felt rooted in the church and developed her own spirituality as a teen. Jewish relatives and friends were part of her orbit, and she felt increasingly drawn to the religion.

When she moved to New York as an adult, she decided to become a Jew, going through Temple Emanu-El in Manhattan, one of the most prominent congregations of Reform Judaism.

Temple Emanu-El on the Upper East Side of Manhattan is one of the largest Reform congregations in the world and the oldest in New York. (Courtesy Temple Emanu-El)

Neither the immigration authority nor the Interior Ministry, which oversees it, responded to a request for comment.

But official responses Vinci received show that decisions in her case zero in on whether her path fits internal regulations drawn up in 2014 to vet conversions performed abroad. The Israeli Supreme Court ruled in 2005 that such conversions, regardless of denomination, must be recognized, leaving it to the ministry to set criteria.

Those rules anticipate in-person study anchored in a congregation; if the course is “outside” the congregation, they require a longer, 18-month track. In Vinci’s case, officials treated her 2020-2021 Zoom coursework as external and concluded she hadn’t met the time or community-involvement thresholds.

IRAC’s legal director for new immigrants, attorney Nicole Maor, appealed the initial rejection, sending in a detailed memo. Maor wrote that congregational classes conducted on Zoom during a pandemic should be considered congregational, rather than external. She argued that the criteria’s purpose is to prevent fictitious conversions — not to penalize sincere candidates who followed their synagogue’s rules during COVID.

“The entire purpose of the criteria is to protect against the abuse of the conversion process. A person who converted in 2021, came to Israel on a Masa program to contribute to Israel in 2022-2023, and stayed in Israel to work and support the country in its most difficult hour after Oct. 7 deserves better and more sympathetic treatment,” she wrote.

She also wrote that the ministry had ignored evidence of Vinci’s Jewish communal life in Israel, from school prayer with students to weekly Orthodox Shabbat meals with a host family.

As part of Vinci’s appeal packet, Kahn submitted a letter describing the cadence of Vinci’s studies: roughly five months in Temple Emanu-El’s Intro to Judaism course alongside his own one-on-one meetings beginning Dec. 21, 2020, and continuing “1-3 times a month for 2-3 hours” until her November 2021 conversion — about 11 months in total. He listed key books and practices he assigned and attested to her active participation in synagogue young-adult programming.

A host family in Netanya provided a letter saying Vinci spent “Shabbat with our family every weekend as well as most holidays,” describing a year of Orthodox observance in their home and an ongoing relationship since she moved to Tel Aviv after Masa. The school where she taught also wrote in support.

The ministry was unmoved.

In an interview, Maor, who handles a large caseload of prospective immigrants, said Vinci’s case is emblematic of a larger phenomenon.

“It’s not just bureaucracy,” Maor said. “There’s a recurring theme — a suspicious attitude at the ministry that has become worse in recent years and makes life much more difficult for converts.”

Vinci’s case sits at the fault line between Diaspora practice after COVID and Israeli bureaucracy. Around the world, Reform and Conservative congregations shifted classes, and in some communities, services, to Zoom. Many have retained hybrid models because they work for busy or far-flung learners.

“This reality has led to a widening gap between how Diaspora congregations operate and the demands of the Interior Ministry,” Maor said.

There is also a philosophical mismatch: For the ministry, involvement in the Jewish community post-conversion appears to mean synagogue membership and attendance logs. For non-Orthodox streams, Maor said, Jewish life can be expressed in multiple ways — home ritual, learning circles, social-justice work — especially in Israel, where Jewish rhythms permeate public life.

In Vinci’s Netanya year, that life included like daily school prayer, holidays with an observant host family, and teaching in a religious environment. Maor argues that should count.

Kahn, who says two of his other converts have made aliyah without incident, said he was saddened by Vinci’s rejection given her devotion and the hoops she jumped through to satisfy paperwork and timelines.

“It wasn’t like she was mucking around in Israel, she was really doing the work and legitimately devoted to being Jewish,” he said.

After losing her legal status and appeal, Vinci returned to the United States. She took a legal-assistant job in Kansas City and is scraping together fees to file a court petition.

Maor won’t predict the outcome, but she said often cases settle before a precedent is set. The state agrees to a compromise such as additional months of study, rather than risk a ruling that forces a policy shift.

Vinci hopes the case determines not only where she celebrates the next set of holidays, but also improves how Israel treats a growing cohort of would-be immigrants whose Jewish journeys began on a laptop during a once-in-a-century shutdown and amid rising antisemitism.

“I hope my story sheds light on inter-community love and acceptance,” she said. “In our current political and social climate, the best thing we can do is be united as one.”

JD Vance arrives in Israel as ceasefire totters: ‘We are in a very good place’

Vice President JD Vance arrived in Israel Tuesday, telling reporters that he felt “very optimistic” that the ceasefire between Hamas and Israel would hold despite Israel’s strikes over the weekend in Gaza following the deaths of two soldiers.

“We are one week into President Trump’s historic peace plan in the Middle East, and things are going, frankly, better than I expected that they were,” Vance told reporters. He spoke alongside U.S. Special Envoy to the Middle East Steve Witkoff and administration adviser Jared Kushner, who helped broker the deal.

Vance is expected to meet with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu Wednesday. The visit marked Vance’s first time in Israel as vice president.

“We will talk about two things, mainly the security challenges and the diplomatic opportunities we face,” Netanyahu said in a speech to the Knesset Monday about his planned meeting with Vance. “We will overcome the challenges and seize the opportunities.”

During his opening remarks at the new Civilian Military Co-operation Center in southern Israel, Vance also accused the “American media” of having a “desire to root for failure” when there are lapses in the ceasefire rollout, appearing to reference Israel’s strikes in Gaza on Sunday.

“Every time that there’s an act of violence, there’s this inclination to say, ‘Oh, this is the end of the ceasefire,’” said Vance. “It’s not the end. It is, in fact, exactly how this is going to have to happen when you have people who hate each other, who have been fighting against each other for a very long time. We are doing very well. We are in a very good place.”

Vance added that his presence in Israel had “nothing to do with events in the past 48 hours,” and said he had come to “put some eyes” on the negotiations and report back to President Donald Trump.

On Tuesday morning, Trump wrote on Truth Social that the United States’ allies in the Middle East would “welcome the opportunity” to “go into GAZA with a heavy force and ‘straighten out Hamas’ if Hamas continues to act badly, in violation of their agreement with us.” (The two Israeli soldiers in Gaza were not killed by Hamas, according to Israel and Hamas.)

“I told these countries, and Israel, ‘NOT YET!’ There is still hope that Hamas will do what is right. If they do not, an end to Hamas will be FAST, FURIOUS, & BRUTAL!,” Trump’s post continued.

While all of the 20 living hostages in Gaza were released by Hamas on Oct. 13, the slow pace of the return of the remaining deceased hostages has spurred frustration among Israelis. At least 13 bodies have been returned to Israel thus far, and two more are scheduled to be returned Tuesday evening.

When asked by a reporter at the press conference Tuesday if the United States would impose a deadline on Hamas for the release of the remaining hostages, Vance urged “patience.”

“This is not going to happen overnight. Some of these hostages are buried under thousands of pounds of rubble. Some of the hostages nobody even knows where they are,” said Vance. “That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t work to get them, and that doesn’t mean we don’t have confidence that we will, it’s just a reason to counsel in favor of a little bit of patience.”

Later, when asked by a reporter how much time Hamas has to lay down its weapons before the U.S. military intervenes, Vance declined to set a strict deadline.

“We know that Hamas has to comply with the deal, and if Hamas doesn’t comply with the deal, very bad things are going to happen,” said Vance. “But I’m not going to do what the President of the United States has thus far refused to do, which is put an explicit deadline on it, because a lot of this stuff is difficult. A lot of this stuff is unpredictable.”

Kushner, the president’s son-in-law, said that there had been “surprisingly strong coordination” between the United Nations and Israel on delivering humanitarian aid into Gaza, and that plans to help rebuild the enclave were underway.

“There are considerations happening now in the area that the IDF controls, as long as that can be secured, to start the construction as a new Gaza, in order to give the Palestinians living in Gaza a place to go, a place to get jobs, a place to live,” said Kushner.

Vance, who is scheduled to remain in Israel until Thursday, also emphasized that U.S. troops would not be on the ground in Gaza and that they were working towards establishing an “international security force” in the region.

“Right now, I feel very optimistic. Can I say with 100% certainty that it’s going to work? No, but you don’t do difficult things by only doing what’s 100% certain, you do difficult things by trying,” said Vance.

Daniel Naroditsky, Jewish chess grandmaster and influential streamer, dies at 29

Daniel Naroditsky, a Jewish chess grandmaster and former child prodigy who became one of the game’s most popular voices through his streaming, commentary and teaching, has died at 29.

Naroditsky’s death was announced Monday by the Charlotte Chess Center, a chess academy in North Carolina, where he worked as a head coach. Information on his survivors and a cause of death was not immediately available.

“It is great sadness that we share the unexpected passing of Daniel Naroditsky. Daniel was a talented chess player, commentator, and educator, and a cherished member of the chess community, admired and respected by fans and players around the world. He was also a loving son and brother, and a loyal friend to many,” the Naroditsky family wrote in a statement shared by the Charlotte Chess Center.

As a teenager, Naroditsky published books on chess strategy, including “Mastering Positional Chess” in 2010 and “Mastering Complex Endgames” in 2012.

Naroditsky earned his chess grandmaster title, the highest honor given to competitors by the International Chess Federation, in 2013 when he was 17 and had yet to graduate high school.

He was an active content creator on Twitch and Youtube, where he had nearly 500,000 subscribers.

Known as Danya, Naroditsky was born on Nov. 9, 1995, in San Mateo, California to Vladimir Naroditsky and Lena Schuman, Jewish immigrants who came to the United States from Ukraine and Azerbaijan, respectively. Naroditsky attended Ronald C. Wornick Jewish Day School in Foster City, California and was bar mitzvahed at Peninsula Temple Beth El in San Mateo in 2009.

In November 2007, Naroditsky was named the under-12 World Youth Chess Champion, telling J. The Jewish News of Northern California at the time that he “couldn’t play chess without loving it.”

“I played a rabbi,” a 10-year-old Naroditsky said after he earned the title. “He lost right away and instead of losing normally he threw all the pieces in the air and stormed out. I almost laughed.”

He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in history from Stanford University in 2019 after taking a year off to play in chess tournaments.

Naroditsky was introduced to the game by his brother, Alan, at just 6 years old and quickly developed an aptitude for the game.

“I think a lot of people want to imagine that it was love at first sight and that my brother couldn’t pull me away from the chessboard,” Naroditsky told the New York Times in 2022, when he was introduced as its chess columnist. “It was more of a gradual process, where chess slowly entered the battery of stuff we did to pass the time. A lot of my best memories are just doing stuff with my brother.”

In his last video uploaded to YouTube, titled “You Thought I Was Gone!? Speedrun Returns!,” Naroditsky told his fans that after a brief pause he was “back and better than ever.”

“I still can’t believe it and don’t want to believe it,” tweeted Dutch grandmaster Benjamin Bok about news of Naroditsky’s death. “It was always a privilege to play, train, and commentate with Danya, but above all, to call him my friend.”

At the time of his death, Naroditsky was ranked in the top 160 players in the world and the top 20 players in the United States, according to the International Chess Federation. He especially excelled at a fast-paced version of the game called blitz chess, for which he maintained a top 25 ranking throughout his adult career.

Naroditsky’s father, Vladimir, died in 2019.

“We ask for privacy for Daniel’s family during this extremely difficult time,” the statement from his family continued. “Let us remember Daniel for his passion and love for the game of chess, and for the joy and inspiration he brought to us every day.”

My Jewish studies students aren’t talking about Israel or antisemitism. They told me why.

I first noticed something was off on the first day of class. I had given my students in my “Sociology of American Jewish life” course at Tulane University blank index cards, asking them to write five words they associate with American Jews. The word antisemitism didn’t appear once, and neither did Israel.

Last week, it happened again. When I asked students to choose topics from the 2020 Pew report on American Jews for small group discussions, no one chose antisemitism or Israel.

What was going on? Antisemitism dominates conversations among lay leaders, philanthropists and academics. Universities are launching new antisemitism studies centers. Yet here were 20 Jewish studies students avoiding the subject. The Hillel director confirmed he’d seen the same pattern: low attendance at events on these topics.

So I turned to my students — almost all Jewish themselves — and asked them to write anonymous reflections on this pattern. I wanted them to help me understand what felt like a significant shift from previous years, when these topics dominated classroom discussions.

Here is what I learned:

My students are exhausted. Not physically tired, but soul-weary from the constant barrage of antisemitism they encounter online. “Seeing constant antisemitism and antizionism has just made me so tired of it that it’s easier to ignore,” one wrote. “When I’m in Jewish spaces, I prefer to focus on the positive things … because it feels like antisemitism is a battle we’re already losing.”

They see antisemitism everywhere on social media — on Instagram, TikTok, even in comment sections barely related to Jewish topics. It’s become so normalized that one student admitted they “don’t even get surprised anymore when I see crazy antisemitism.” Another described it as being talked about “on the news so much as well as talked about in everyday life” that bringing it down further in class feels redundant.

But perhaps most revealing was this: They want their Jewish studies classroom to be different. “When I am in class, I enjoy learning about new topics and not about topics that I already talk about and experience every single day,” one student explained. Another put it more bluntly: “I don’t want the thing I bring up when talking about Judaism to be antisemitism in a class setting, where it is something we deal with all the time outside of it.”

The Israel conversation has become even more fraught. Students described being paralyzed by the fear of “saying the wrong thing by accident.” The topic has become so contentious that it’s “a very sensitive time period because of October 7th,” making people hesitant to speak up even in Jewish spaces. One student noted that discussing Israel has become “a dividing point even within the Jewish community,” creating rifts with family members and friends.

The pressure to be perfectly informed weighs heavily on them. ‘I don’t feel as educated on that, and in most contexts, I don’t want to bring it up because I don’t want to say the wrong thing by accident,’ one student confessed. They feel caught between the expectation to have authoritative opinions as Jews and their honest uncertainty about complex issues. Another described finding it ‘hard to delve into’ topics when unsure if they’re conveying accurate information. This burden of representation — the unspoken expectation that every Jewish student must be an articulate defender of their people — has become another silencing force.

I don’t take this silence as apathy, but rather about self-preservation. My students are keenly aware that even among close friends, there might be hidden antisemitism. They’ve learned to perform constant risk assessments about when and where it’s safe to express their views. As one observed, people are either intensely engaged with these topics or “have little to no interest talking about it … and don’t feel comfortable sharing their opinions.”

What struck me most was their desire to reclaim Jewish identity from being primarily defined by hatred against Jews. These young Jews want to explore their heritage, culture, and traditions without every conversation circling back to those who despise them. They’re not in denial — they know antisemitism exists. They’re just tired of it taking up so much space in their Jewish lives.

This generational shift matters. While Jewish institutions pour resources into combating antisemitism and defending Israel — crucial work, to be clear — our young people are signaling they need something more. They need spaces where being Jewish isn’t synonymous with being embattled. They need opportunities to engage with Jewish life, learning, and culture on its own terms.

My classroom revelation taught me this: If we want to engage the next generation, we need to balance necessary vigilance with joyful exploration of what makes Jewish life meaningful. Our students aren’t abandoning the fight — they’re asking for the chance to remember what we’re fighting for.

A US military base canceled a children’s event celebrating a pioneering Jewish woman cyclist, citing DEI ban

A children’s museum housed on a U.S. military base cancelled a planned storytime reading celebrating the life of a pioneering 19th-century female Jewish cyclist earlier this year, after the book was flagged under a military-wide ban on “DEI” content.

The stated reason was because the book was about a woman, its author, Mary Boone, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

“If they had actually read the book and found out it was about a Latvian Jewish immigrant, it would have been a double whammy,” Boone said.

The recently revealed reason for the cancellation is the latest example of how a broad crackdown on diversity initiatives throughout the U.S. military, under Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, has pushed out Jewish representation as well.

Earlier this year the U.S. Naval Academy removed a display honoring Jewish female graduates ahead of a planned Hegseth visit. The academy also removed several books about Judaism and the Holocaust from its campus library, while leaving others including “Mein Kampf” intact. The Pentagon additionally removed content about Holocaust remembrance from its websites this spring, prompting a response from Jewish War Veterans of the USA.

The incidents all occurred this spring, immediately following Hegseth’s anti-DEI order. That was also when a military base near Tacoma, Washington, cancelled a planned reading of the children’s book “Pedal Pusher: How One Woman’s Bicycle Adventure Helped Change The World.” The picture book is a biography of Annie Cohen Kopchovsky, who in 1895 became the first woman to cycle around the world.

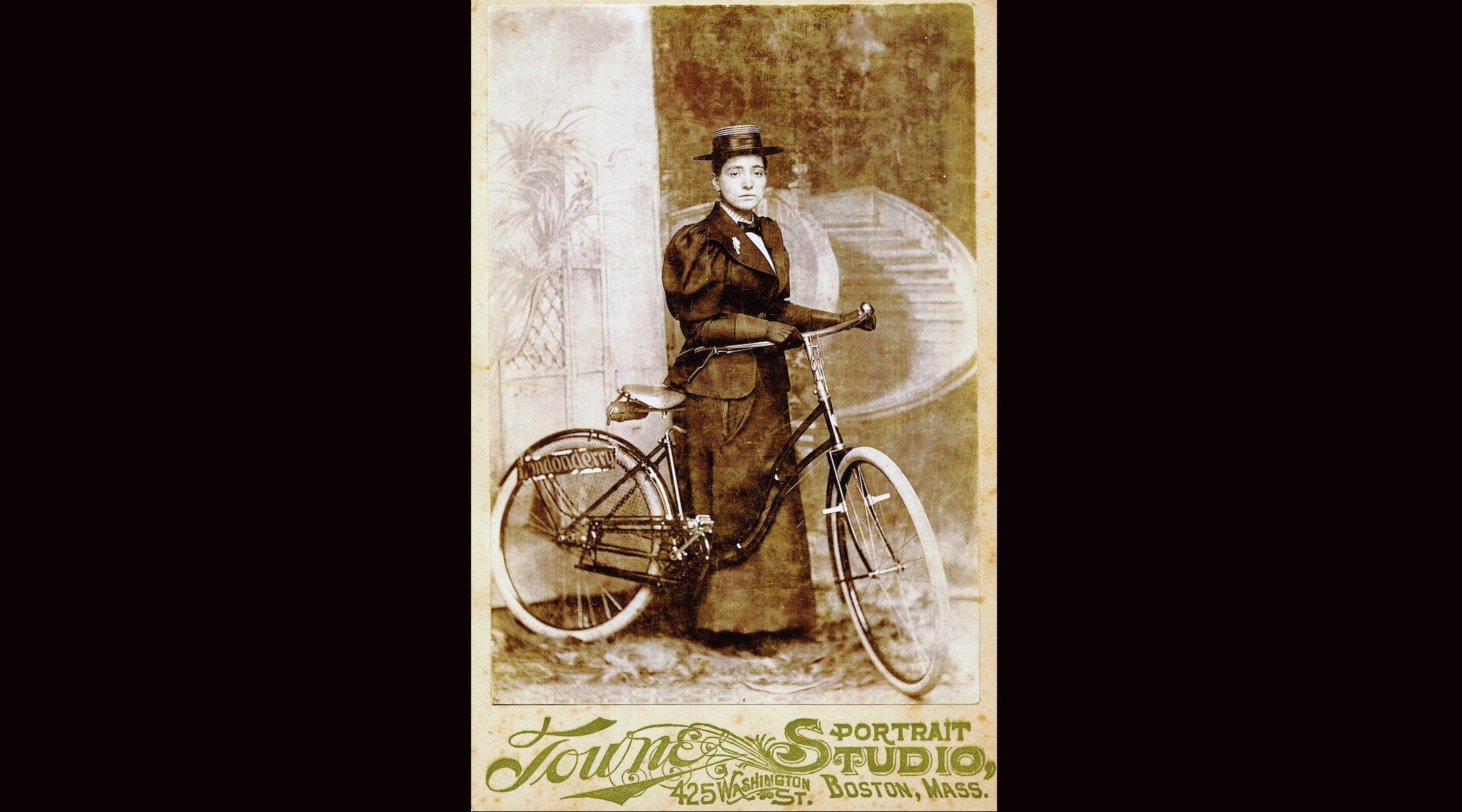

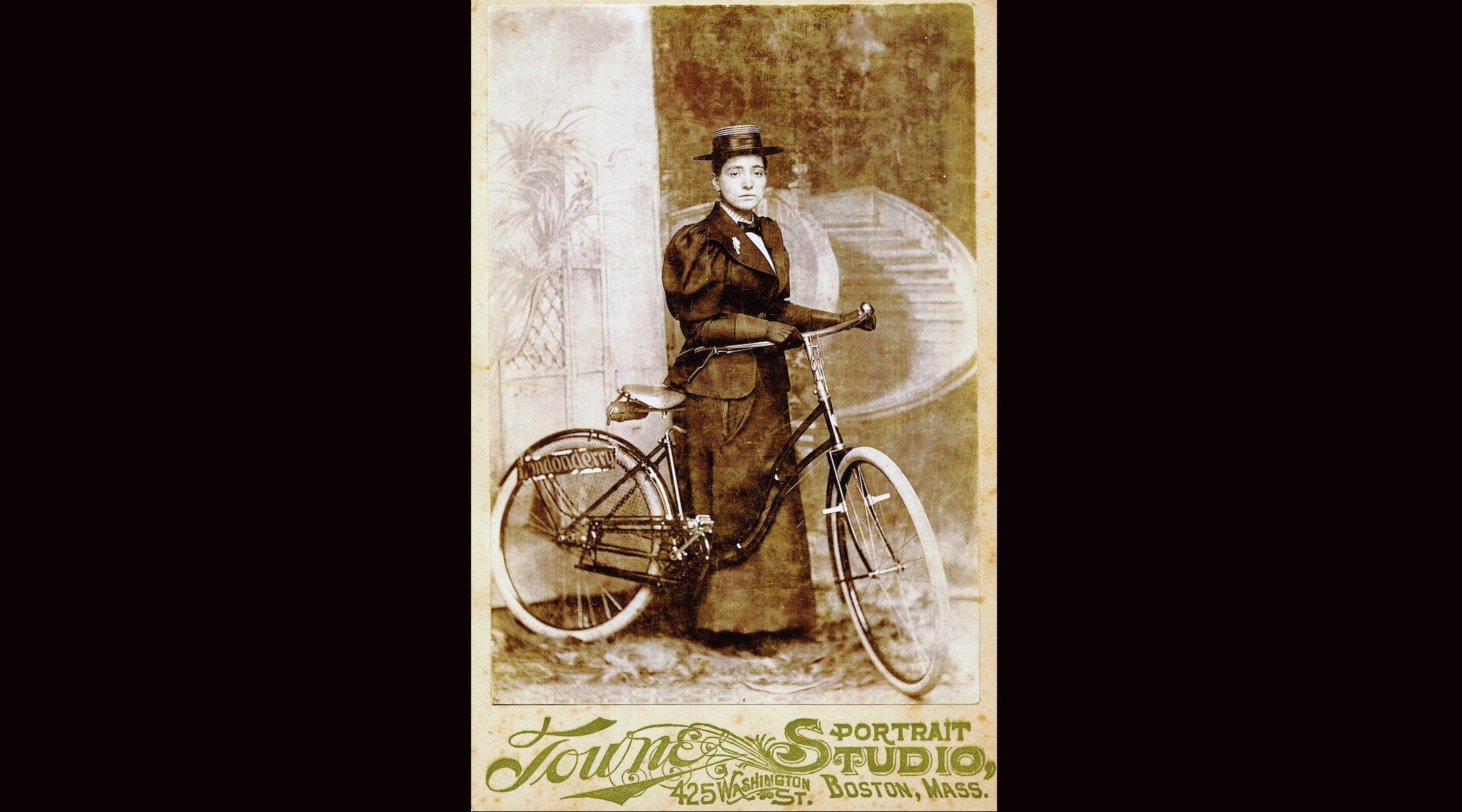

Annie Cohen Kopchovsky, a.k.a. “Annie Londonderry,” poses with her bike she used to cycle around the world in the 1890s.

The talk featuring the book’s author was scheduled to be held this past March, during Women’s History Month, at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, home to around 110,000 people including service members and their families. Boone, a Tacoma resident, revealed the reasons behind the cancellation in a Seattle Times op-ed on Oct. 11, in recognition of Banned Books Week.

“Four days before the event, I was told it violated the administration’s executive order restricting so-called ‘radical’ Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion programs across federal institutions,” she wrote. “Someone complained when they saw my story time being promoted. Museum higher-ups appealed to military attorneys, who ruled that the program about a pioneering cyclist was out of bounds.

“Let that sink in: the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. military had effectively declared a woman on a bike too threatening for children.”

A representative for Joint Base Lewis-McChord declined to comment, citing reduced office functions owing to the ongoing government shutdown.

Boone, who is not Jewish but is married to a Jew, told JTA that she was led to believe someone on the base had complained after seeing a poster advertising the reading. She doubts that those objecting to the book had actually read it, but rather had reacted because “it was a book about a woman.”

A section of the book briefly mentions Kopchovsky’s Jewish and immigrant identity as one reason why her journey, as a mother of three circumnavigating the globe by bike in 1895, was so improbable.

“Annie was a Latvian Jewish immigrant, and this was a time when prejudice toward Jewish people was widespread,” the book reads.

Initially, Boone said, she had not planned to include the section in the book, which only runs to 700 words. “My editor called and said, ‘This is a huge part of her story you left out,’” the author recalled. She said she responded, “I’m not a Jewish writer. Can I tell this? She was like, ‘Yes, you can tell this.’” The passage made the book.

Greentrike, a nonprofit that operates the base’s museum as well as a different children’s museum in Tacoma, declined to comment. Another March event featuring Boone at the Children’s Museum of Tacoma, off base, went forward as scheduled.

The Seattle Times obtained an email from Greentrike outlining the military’s reasons for the book’s cancellation as part of the op-ed’s fact checking process.

In March, the museum had initially announced the events “in celebration of Women’s History Month,” saying the readings would be paired with children’s activities including bike safety lessons. A brief update announcing the military base event’s cancellation only stated that storytime “will not be taking place at this time and has been removed from the event calendar.”

Back in 1895, Kopchovsky set off on her bicycle journey from Boston as part of a wager between two men who had placed bets on whether it was possible for a woman to cycle around the world. Initially pedaling west, she reached Chicago and almost gave up before ditching her heavy women’s bicycle for a lighter and more practical men’s model, then set off back east — eventually sailing on to bike in Europe and Asia before heading back to Chicago.

During her travels, Kopchovsky went by “Annie Londonderry” — not to disguise her Jewish identity, but because she had struck a sponsorship deal with the mineral-water company Londonderry Lithia. She earned $10,000 for her ride and wrote often about it after her return, frequently embellishing her tales of derring-do.

Children on the base have still received multiple opportunities to hear about Kopchovsky. When the storytime cancellation was initially announced, Boone said, she was contacted by representatives from two public schools also housed on base. She wound up speaking at both of them, without incident.

Months later, after she went public with the initial cancellation, she was swarmed with speaking invitations and sales of her book picked up. Among the new connections she made were to distant relatives of Kopchovsky.

“It’s given me the opportunity to talk about her to a lot more people who are outraged that this book about a woman would be cancelled,” she said.