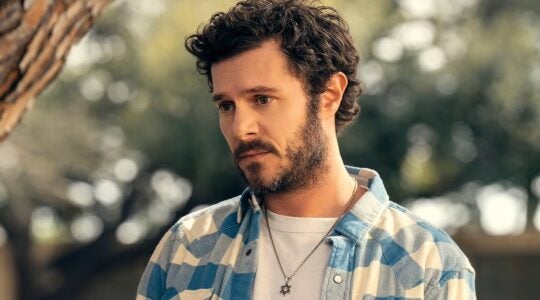

LOS ANGELES (JTA) – While researching his latest one-man show, “Our Great Tchaikovsky,” Hershey Felder — a playwright, actor and composer who has brought the loves, torments and soaring music of some of the world’s greatest composers to the stage — faced a moral question.

Does towering talent exculpate a composer, or any artist, for a racist or anti-Semitic remark, even at a time and place where such comments were commonplace?

The answer isn’t simple.

“This is a very complicated matter,” Felder, 49, who was raised in a Yiddish-speaking home in Canada, told JTA in a phone interview.

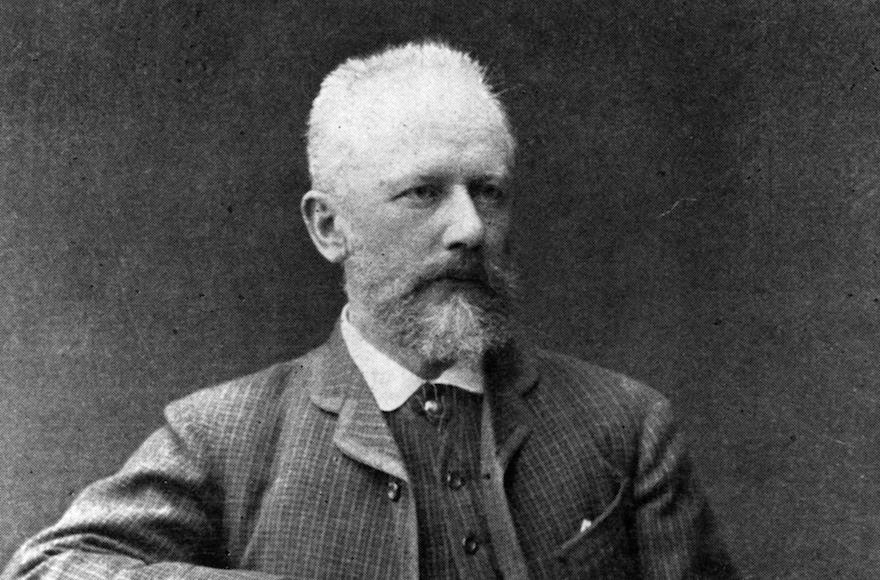

In a letter written in 1878, Pyotr (Peter) Ilyish Tchaikovsky wrote that when his train stopped at a Russian railroad station, he noticed “a mass of dirty Yids, with that poisoning of the atmosphere which accompanies them everywhere.”

“Tchaikovsky was a man of the 19th century, when the intelligentsia in Russia and other European countries was anti-Semitic almost by reflex,” said Felder, whose father survived Auschwitz.

By way of analogy, Felder noted that George Gershwin, living in New York and Los Angeles, commonly referred to his 1925 one-act jazz opera “Blue Moon,” the predecessor to “Porgy and Bess,” as his “nigger opera.”

Although considered extremely offensive now, in the 1920s and ’30s — when Al Jolson regularly performed in blackface — such an appellation, while certainly derogatory, hadn’t become what journalist Farai Chideya has called “the nuclear bomb of racial epithets,” at least among most white Americans.

“Porgy and Bess” premiered in New York in 1935 with an all-black cast, and is still embraced by many African-American performers. Did Gershwin’s use of the epithet mean that he was racist? Felder asked.

Answering his own question, he said, “We can’t correct or apologize for history, and I don’t feel that I have to go into that aspect [of Tchaikovsky’s life] in my stage presentation.”

Also, Felder added, Tchaikovsky’s putdown of “Yids” was countered by his actions. He provided a scholarship from his own pocket for the young Jewish violinist Samuli Litvinov; he maintained a deep friendship with composer-conductors Anton and Nikolai Rubenstein; and he defended Felix Mendelssohn against Richard Wagner’s anti-Semitic slurs.

What Tchaikovsky feared most was that he would be outed as a homosexual, Felder said, which would have ruined him and led to likely exile in Siberia. To scotch rumors, Tchaikovsky married — an idea that would prove disastrous. The union lasted less than three months and the ex-spouse would extort blackmail payments for a lifetime.

The composer’s struggle with his homosexuality — compounded by his fear of exposure — is a central motif through Felder’s performance. While Felder uses a Russian-inflected accent while speaking as Tchaikovsky, he reverts to his own voice and accent when denouncing the discrimination and persecution suffered by gay men in Russia, then as now.

The same struggle also is reflected in Tchaikovsky’s music, Felder said, nowhere more clearly than in his Sixth Symphony, the “Pathetique.” The composer conducted its premier performance in St. Petersburg in 1893, and he died suddenly nine days later at 53.

Initially, his death was attributed to cholera, but a widespread belief persists that Tchaikovsky committed suicide.

Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s works include six symphonies and three piano concertos, only two of which are finished, a violin concerto and 11 operas. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

As for Felder, he has steadily added to his repertoire of one-man musical bio-dramas over the past 22 years. His productions have celebrated the lives and works of classical giants Ludwig van Beethoven, Frederic Chopin and Franz Liszt, as well as more contemporary (and Jewish) composers Gershwin, Irving Berlin and Leonard Bernstein.

In “Our Great Tchaikovsky,” audiences get a generous sampling of the Russian master’s work, from such favorites as the “1812 Overture,” selections from “The Nutcracker” and “Swan Lake,” to the little-known “Jurisprudence March.”

Not all reviews of Felder’s presentations have been ecstatic, but the large majority have been highly laudatory — especially compared to the sharp criticism that many of Tchaikovsky’s works received in his lifetime.

The current run of “Tchaikovsky” was extended for a third week, to Aug. 13, even before the July 19 opening at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Beverly Hills. The show will move to the Hartford Stage in that Connecticut city, Aug. 19-27.

In late September and early October, Felder will return to London for overlapping runs as Berlin and Bernstein at the Other Palace, a theater in the West End. After that, Felder said he will select one final composer, not yet chosen, as the final entry in his lineup of one-man concert plays.

He then expects to concentrate on creating his own compositions, which currently include the “Aliyah” concerto, the opera “Noah’s Ark” and a recording of love songs from the Yiddish theater.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.