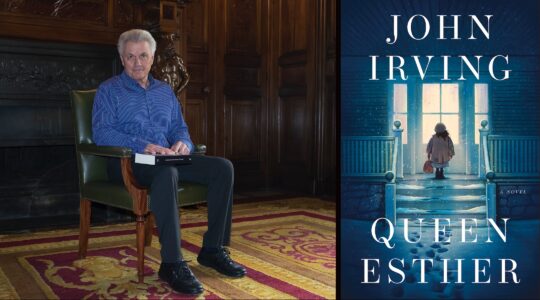

While the availability of less expensive kosher cheese has been a boon to observant Jews, greater culinary sophistication in the Orthodox community is also having an effect on the dairy market, experts say. (Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

This story is sponsored by the Orthodox Union.

It’s early morning in the Sardinian countryside and a farmer is milking his sheep while an Orthodox Jewish kosher supervisor looks on.

The supervisor, known as a mashgiach, is sleeping in the farmer’s barn, and he’ll be there all week.

Welcome to the world of kosher cheesemaking.

The weeklong kosher cheese run in Sardinia is just one of a number of methods that artisanal kosher cheesemaker Brent Delman, owner and founder of The Cheese Guy, uses to manufacture products for kosher consumers who have developed a taste for fine Italian cheeses.

“I like to partner up with the most authentic suppliers of non-kosher cheese and see if we can replicate it. This requires flying in Jews from mainland Italy and bringing them to Sardinia to watch the milking of the sheep,” said Delman, an Ohio native, explaining that many of the farmers he works with have never met Jews before the mashgiach shows up to inspect their operation.

The incongruous sourcing partnerships are a sign not only of the complexity of kosher cheese production, but also of the growing taste among kosher consumers for artisanal cheeses and greater cheese variety.

A number of mainstream cheese producers have begun large-scale kosher cheese production in recent years. In 2015, the Kraft subsidiary Polly-O generated excitement among consumers when it began producing Orthodox Union-certified kosher string cheese, undercutting the existing kosher competition significantly on price. Wisconsin’s Lake Country Dairy, a subsidiary of Schuman cheese, has been making millions of pounds of kosher Italian-style Parmesan, Asiago, Romano and mascarpone for about a decade. Smaller artisanal cheesemakers, like the Seattle-based Beecher’s, are also making kosher versions of their flagship cheeses.

Many hard cheeses use rennet, an animal byproduct, in production and therefore are not kosher. To be certified as kosher, hard cheeses not only must use synthetic rennet, but all the equipment and ingredients must be kosher and a mashgiach has to supervise the production.

Until recently, kosher Danish blue cheese and fine parmigiana were almost impossible to find; likewise for Brie and other fine soft cheeses. But with the market for kosher products growing – studies show that in addition to the burgeoning Jewish kosher market, many non-Jews prefer kosher because they associate it with increased cleanliness and healthfulness – increasing numbers of cheesemakers are getting into the kosher market.

“Companies that never would have considered making kosher cheese now do because they see their competitors succeeding with it,” said Rabbi Avrohom Gordimer, a dairy expert in the O.U.’s kosher division. “These major cheese companies have taken the kosher plunge and chosen the O.U. certification, as it is the most recognized kosher symbol today.”

Typically, rather than convert entire facilities to kosher production or keep kosher supervisors on site year-round, large companies will do a special kosher run – perhaps once a month, or in some cases for a few hours each day. During the kosher campaign, non-kosher production is shut down, all relevant equipment is cleaned and rabbinical supervisors oversee production.

“Take a cheddar cheese company in Vermont, where the good cheddar comes from,” said Rabbi Abraham Juravel, the supervisor of technical services for O.U.’s kosher division. “They’re not going to pay a rabbi to stay there whenever they make cheddar cheese; it’s too expensive. They’ll make a run once or twice a year with a rabbi present, and then they can market the cheese from those days as kosher.”

To be certified as kosher, hard cheeses not only must use synthetic rennet rather than animal-byproduct rennet, but all the equipment and ingredients must be kosher and a mashgiach must supervise the production. (Orthodox Union)

Lake Country Dairy produces some 26 million pounds of cheese per year, including 4 million pounds of kosher mascarpone, Parmesan, Romano, Asiago and fontina sold under the brand names Bella Rosa, Cello Riserva and Pastures of Eden.

Kosher certification “symbolizes higher quality and more attention to detail in selecting the ingredients,” said Jesse Norton, Lake Country Dairy’s quality assurance director, who said the company’s entry into the kosher market a decade ago “dovetails well with our philosophy of meeting the needs of customers and doing what other groups find difficult to do.”

For a large company capable of mass-producing cheeses, going kosher makes good business sense, giving the company a competitive advantage, Norton said. As more companies go kosher, consumers should see better prices, he noted.

While the availability of less expensive cheese has been a boon to observant families, greater culinary sophistication in the Orthodox community is also having an effect on the dairy market, according to Gordimer.

“People want more variety. Their tastes have become more sophisticated,” he said.

This trend is of a piece with American consumers generally, where in recent years consumers have developed a taste for artisanal foods, locally sourced products, craft beers and other high-quality offerings. U.S. retail sales of natural and specialty cheeses reached $17.4 billion in 2015, an increase of 4.1 percent since 2011, according to a report by Packaged Facts.

Cheese consumption is rising, too: In 2016, Americans consumed 5.35 million metric tons of cheese, a 7.6 increase from 2014, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

For the major cheese producers like Kraft, economies of scale means that prices for kosher-certified products can be similar to non-kosher cheese. Not so for smaller companies, which typically charge a premium for kosher cheese to cover the costs of kosher production and certification. Products made with cholov yisroel – milk produced solely by Jews, reflective of a more stringent level of kosher preferred by some strictly Orthodox consumers – can be two or three times as pricey as non-kosher cheese.

Until about a decade ago, the kosher cheese world was like the kosher wine market 30 years ago: There were the basics, but little for the discerning connoisseur, according to Delman, The Cheese Guy. Just as fine kosher wines from Israel replaced the ubiquitous Manischewitz at kosher dinner tables, fine kosher cheeses are also now commonplace, he said.

Delman’s production shows the challenges of small-scale, fine-cheese production. For example, to manufacture a beer cheddar he is producing in cooperation with a dairy farm in Vermont, Delman first must arrange for kosher supervisors to accompany him to the facility. They clean the lines and check that all the ingredients are kosher; only then does production start.

Cheeses like Swiss and feta are made in brine, which must be kept separate from non-kosher cheeses. Because most facilities don’t have extra brine tanks, Delman has to bring his own brine and cheese molds, further driving up costs.

“All of my products are small-batch artisanal productions, so the challenge of the kosher fees automatically makes the product more expensive,” he said.

Juravel says mass production is particularly difficult when it comes to cheese, so kosher cheese will always be something of a challenge. But it’s worth it.

“Cheesemaking is an art,” Juravel said. “There’s science behind it, but it’s an art.”

(This article was sponsored by and produced in partnership with the Orthodox Union, the nation’s largest Orthodox Jewish umbrella organization, dedicated to engaging and strengthening the Jewish community, and to serving as the voice of Orthodox Judaism in North America. This article was produced by JTA’s native content team.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.