TEL AVIV – In the summer of 1942, while Nazi officials in Wannsee were coining the term “Final Solution,” Leni Sonnenfeld donned a crisp sundress and smiled into a camera in New York City’s Central Park.

At her side was her husband, Herbert, dressed in a starched U.S. Army uniform. In the photo he’s confident and casual, his hands in his pockets and his legs spread wide. She is elegant and poised, a quiet smile on her lips. They are young and clearly in love.

Staring at the attractive pair in the snapshot — a rare one in which the couple appears in front of the camera — it’s hard to believe the Sonnenfelds bore witness to some of the most momentous Jewish events of the 20th century. From 1933 until the dawn of the 21st century, the two photojournalists — German-born Jews who settled in the United States just before World War II — tasked themselves with documenting Jewish life across an ever-turbulent globe.

Their images of Israel’s nascent kibbutz society, of Jewish rituals in Iran and Morocco, and of the Zionist symposiums that indelibly changed the shape of post-Holocaust Jewish existence offer a sweeping and yet surprisingly intimate record of 70 years of crucial, tenuous history.

Known as the Sonnenfeld Collection, the 500,000 images are owned today by Beit Hatfutsot-The Museum of the Jewish People.

Leni and Herbert Sonnenfeld in New York City’s Central Park, 1942. (Courtesy of Beit Hatfutsot)

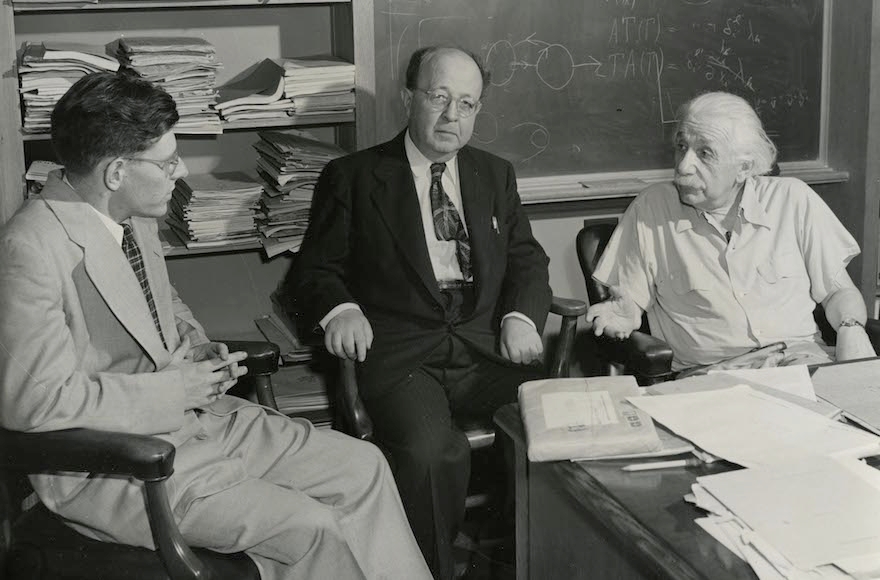

There is Albert Einstein making small talk with visitors at Princeton University in the 1950s. There is a Holocaust survivor working on a 1960s Israeli kibbutz, his tanned, toned body showing diametric opposition to the numbers inked onto his forearm. There is a bar mitzvah in Morocco and a German youth resistance group boarding trains from Berlin to Marseilles. And there are refugees — so many refugees — spilling from boats and trains and alighting in Haifa, New York and other ports across the globe.

And now, thanks to The Museum of the Jewish People’s digital overhaul of its archives, the images will be available to the public and fully searchable online for the very first time.

“It’s a gift that you can’t stop admiring,” says Rachel Snold, director of the Bernard H. And Miriam Oster Visual Documentation Center at Beit Hatfutsot, of the collection.

The Sonnenfelds started taking photographs in Germany in 1933, when Herbert, an insurance expert, was laid off from his job in the first wave of sweeping anti-Semitic laws passed by the Nazi regime. The couple, sensing the evil that was afoot, took an exploratory trip to what was then the British Mandate of Palestine.

When she saw her husband’s developed photos, Leni realized that Herbert’s snapshots from the trip — Jewish children dancing in a circle on a Haifa-bound ship; Jewish and Arab workers conversing in the hot sun of a kibbutz — deserved to be published. She peddled the images to a number of Jewish newspapers and magazines, and Herbert’s career as a press photographer was born.

At first, Leni served as her husband’s assistant. But as the years passed her camera skills grew, and soon the couple worked as a team of equals.

As the Nazis grew more bold and Berlin became more sinister, the Sonnenfelds tried to immigrate to Palestine. Under the strict legislation of the British Mandate, however, they were denied the necessary documents.

Instead they made it to New York City in 1939. Herbert became an official photographer for Yeshiva University while Leni traveled, often alone, to some of the most far-flung Jewish communities on the globe — Morocco, Spain, Yemen and Iran, among them — documenting the colorful varieties of global Jewish life. She sold her photos to the likes of The New York Times, Life magazine and Esquire.

“You cannot say which one was more talented, Leni or Herbert,” Snold says. “I’ve thought about it a lot. And when you look at an image from the collection, it’s impossible to tell from the image alone which one of them took the shot. Their style is similar to a film director managing a scene. It’s like they freeze a moment, but at the same time, there is always movement there, always life.”

Herbert Sonnenfeld died in 1972. Leni continued to take photographs for another 30 years, shutterbugging until just before her death in 2004.

She never remarried, and the couple never had children. In 2005, a distant relative in Israel gifted Beit Hatfutsot with the nearly half-million slides, negatives and prints that comprise the Sonnenfeld Collection.

An Arab neighbor visiting a friend in Kibbutz Kfar Giladi, 1945-46. (Herbert Sonnenfeld/Courtesy of Beit Hatfutsot)

The images are stunning, and their crisp quality has been preserved in Beit Hatfutsot’s online archives.

But Snold is hoping for something more: That through the digitization process, the hundreds of faces captured by the Sonnenfelds will be properly identified.

In nearly 90 percent of the images, Snold says, the subjects are still unknown. Putting them online and allowing the public to search the images is the museum’s best hope that Internet users around the world may spot family members or friends, and finally fill in the gaps in the collection’s archives.

“There’s a kind of poetic documentation in these photographs, and you feel like you know the people behind the image,” Snold says. “Now we are hoping people who actually did know the people will see some of the images and let us know who they are.”

(This article is part of a series sponsored by the Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot, the sole institution anywhere in the world devoted to sharing the complete story of the Jewish people with millions of visitors from all walks of life. To learn more, click here.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.