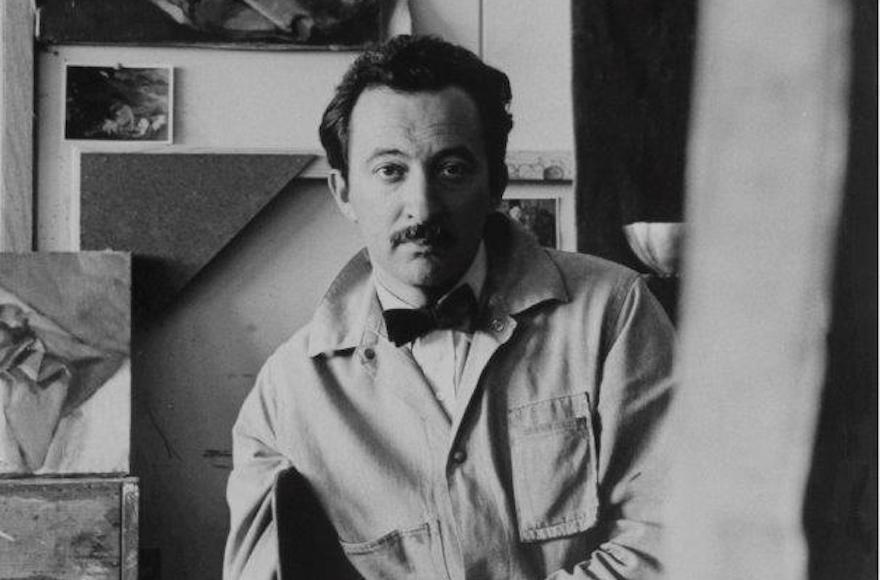

Boston – Golems, rabbis and less-than-holy biblical figures loom large in the legacy of Jewish artist David Aronson, who died Thursday, July 2, at age 91.

Aronson, born in Lithuania and son of an Orthodox Jewish rabbi, rose from the hardships of early 20th century immigrant life to become a preeminent member of the Boston Expressionism movement of the 1940s. The tension between Aronson’s upbringing and creative vision was a major theme in his art and life.

Aronson’s work – including paintings, charcoal drawings and sculptures – merged holy and mundane themes – sometimes in controversial ways. He grappled with big ideas but was also meticulous about technical details, said Bernard Pucker, who sold Aronson’s art from the late 1970s.

“I admired the soul and spirit of his work, plus the genius of the execution,” Pucker told JTA in an interview in his gallery on Boston’s Newbury Street. “There’s a fundamental commitment to humanity that comes through in all of David’s work that doesn’t derive only from his Jewish background but derives from his commitment to humanity.”

Aronson was an artistic institution in Boston, standing out even among other leading Boston Expressionists, like Hyman Bloom, Jack Levine and Karle Zerbe, whom Aronson trained under. A founder of Boston University’s visual arts program in 1955, Aronson was an influential teacher at the university, where he taught for 34 years. He established the Boston University Art Gallery, molded his program into the College of Fine Arts and became a tenured professor of art.

David Aronson’s painting “The Golem” is among his most renowned works. (Braithwaite & Katz)

Among Aronson’s most highly regarded works are “The Golem” (1958), a painting, and The Door (1963-1969), a large bronze triptych – both owned by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Mass. His monumental sculpture Spirit of Israel (1986) stands on the grounds of Brandeis University, outside the Berlin Chapel.

Other of Aronson’s paintings are owned by major museums around the world, including Museum of Fine Arts, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Jewish Museum in New York and the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University. Private collectors, synagogues and the Hebrew College in Boston, which awarded him an honorary doctorate, also own his work.

Aronson was born in rural Lithuania in 1923. After emigrating in 1929, his family settled in Boston, where his Orthodox Jewish father earned a living as a kosher meat slaughterer.

Growing up, Aronson’s artistic passion clashed with his father’s firm adherence to the biblical prohibition against creating graven images. Despite his father’s disapproval, Aronson pursued the life of an artist.

After two years at what was then Hebrew Teacher’s College in Boston, he dropped out and in 1941 began professional art training under Zerbe, the patriarch of Boston Expressionism, at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. He quickly achieved recognition, at 23 becoming the youngest artist featured in “Fourteen Americans,” a 1946 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

David Aronson’s monumental sculpture Spirit of Israel stands on the grounds of Brandeis University. (The Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University)

In general, Aronson’s work grapples with faith and the human condition and draws on Christian and later Jewish themes and stories. Paintings such as “Resurrection” (1944), exhibited in the 1946 MoMA exhibition, and “Young Christ with Phylacteries” (1946), stirred controversy among strict Christian and Jewish religionists. But Pucker said Aronson did not aim to offend.

“He was trying to find a visual language which would enable him to talk about fundamental questions,” Pucker said, standing in front of three of Aronson’s later Judaica sculptures. “He was always bouncing between the world of the holy and the profane.”

For instance, many of Aronson’s paintings and sculptures include prolific depictions of angels – angels with books, angels with musical instruments, fallen angels, and in at least one case, an avenging angel.

While neither his art nor his personality was warm and fuzzy, Aronson’s life was filled with love, said Pucker. My sense is that David was always wrestling with his angels, he said, much like Jacob of the Bible.

Aronson is survived by his wife of 60 years, painter Georgiana Nyman Aronson, his son, Ben Aronson, and his two daughters, Judith Webb and Abigail Zocher.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.