Lew Priven, left, and his sister Cheryl Finkelstein, second from right, with their long-lost cousins, Rudolf and Natalya Priven, in Florida, February 2013. (Courtest Lew Priven)

Judy and Lew Priven in 2011 standing next to a sign marking Pavoloch, the village in Ukraine where Lew’s father, Julius, was raised. (Courtesy Lew Priven)

The Seeking Kin column aims to help reunite long-lost relatives and friends.

BALTIMORE (JTA) — Visiting his late father’s ancestral village of Pavoloch in 2011 confirmed some of the images Lew Priven had long held of the place as a real-life Anatevka, the fictional shtetl of “Fiddler on the Roof,” such as the people he saw riding by on horse and wagon.

Then he and his wife, Judy, learned of the horror: The 1,500-member Jewish community, massacred on Sept. 5, 1941, was buried in a mass grave.

The suburban Washington couple was visiting the Ukraine village’s museum, housed in a former synagogue, when they learned of the now-covered pit, so they went off to pay their respects. At the edge of the site, an obelisk in Hebrew and Russian memorializing the killings stood in an open field that once had bordered the village’s Jewish cemetery, although no gravestones attested to it.

The couple left Ukraine figuring that any Priven kin not already in America by the early 20th century were killed in the Holocaust. But soon after they were pleasantly surprised to find that the branch of the family headed by his father’s first cousin, Velvel, lived in Russia during World War II, and Velvel’s son Rudolf had settled in the United States in the early 1990s.

Two months ago, Priven and his sister Cheryl traveled to Florida to meet some of their newfound cousins — Rudolf Priven and his wife, Natalya — for the first time.

Priven, a retired business executive who lives in Chevy Chase, Md., was thrilled at the family’s reconnection.

“Just doing the detective work was exciting, to put it all together,” he said.

Priven was speaking from his home on Sunday night at the start of Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Memorial Day, after returning from a synagogue commemoration.

In the somber time that is Yom Hashoah, it was appropriate as well to celebrate the joy felt by one who had found relatives who escaped the clutches of the Nazis and their collaborators.

Aware of “Seeking Kin” reporting on those who had reunited after being driven apart by the Holocaust, Yad Vashem alerted me to the Privens’ recent meeting.

Yad Vashem, Israel’s official Holocaust commemoration institution, since 2004 has intensified efforts to collect the names of every Holocaust victim. The effort began in the 1950s, when visitors to the Jerusalem museum were encouraged to complete forms about friends or relatives killed in the Shoah. The pages of testimony, as the forms were known, solicited such basic information as victims’ names, ages, professions, hometowns, the ghettos where they were trapped and their circumstances of death.

The Internet age has allowed users to complete the pages from afar and view the older, since-digitized pages on Yad Vashem’s website and learn about Holocaust victims in their family. An unexpected legacy of the pages of testimony: People also can learn about survivors or other relatives, as each page allows the supplier of information to write his or her name and address.

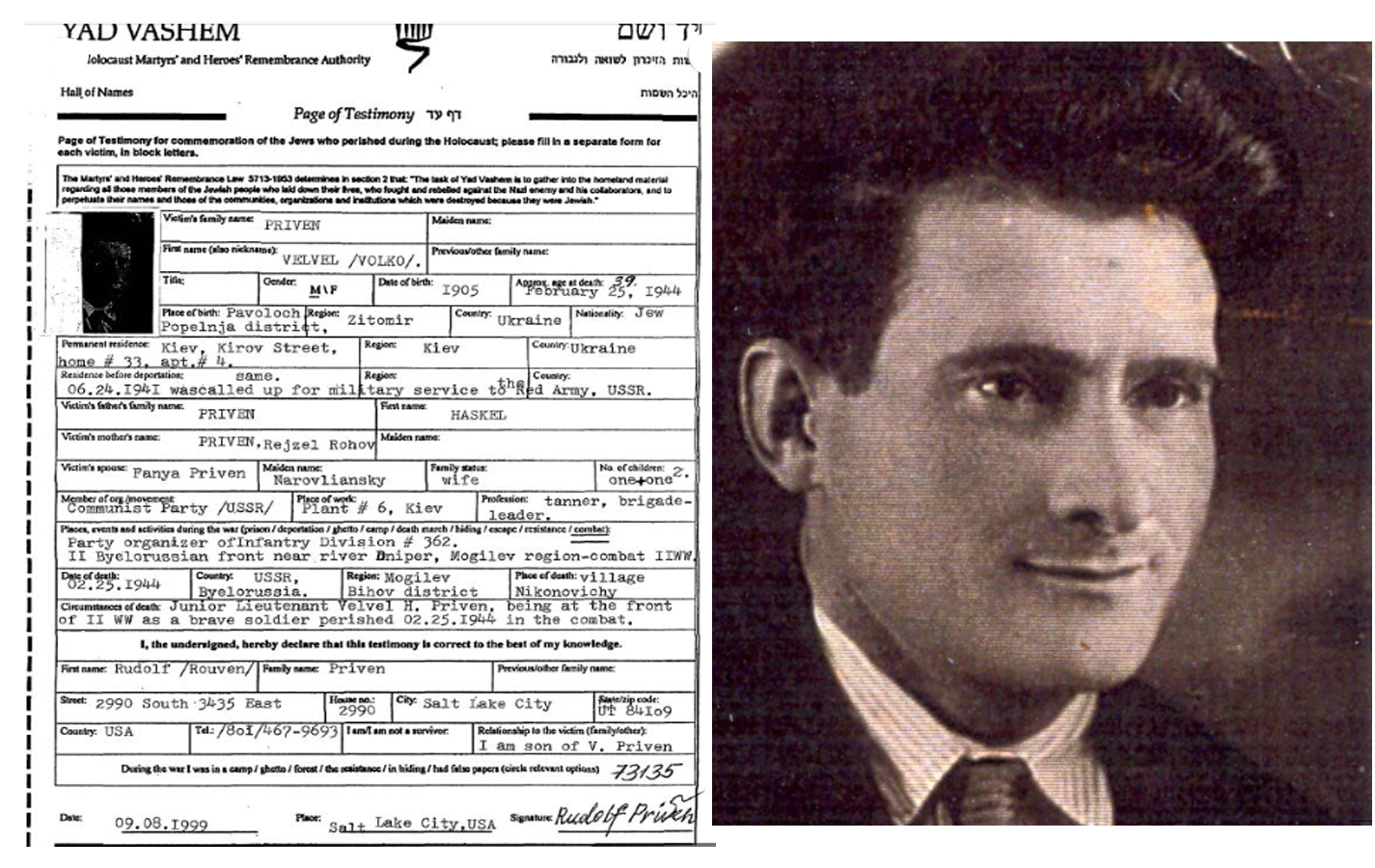

That’s how the Privens came to reunite. Shortly after Lew and Judy traveled to Pavoloch, Cheryl Finkelstein (Lew’s sister) and her husband, Robert, visited Yad Vashem. Robert Finkelstein typed “Priven” into a computer there. One page of testimony he found had been completed by Rudolf Priven to memorialize his father, Velvel, also known as Volko. Velvel Priven was a lieutenant in the Soviet army who was killed in battle in Nikonovichy, a village near Mogilev, on Feb. 25, 1944.

But luck and timing still played a crucial role in the eventual reunification of the Priven cousins. Only in about 2004 did Yad Vashem begin classifying as Holocaust victims those Jewish soldiers in the Soviet military who were killed in battle. Approximately 500,000 Jewish soldiers served in the Soviet military during World War II — 200,000 were killed, the majority after being captured by the Germans rather than being killed in combat, said Cynthia Wroclawski, the manager of Yad Vashem’s Shoah Victims’ Names Recovery Project.

“We consider [Soviet] army soldiers who were Jews to be [Holocaust] victims because it was a known policy that the Nazis would kill Jewish soldiers if they captured them,” she said. “Their fate was sealed. They were targeted as Jews.”

The Priven siblings eventually contacted Rudolf Priven, who had completed the page of testimony in 1999 when he lived in Salt Lake City, Utah, shortly after emigrating from Russia. Now 75, Rudolf Priven is a retired physician who grew up in the Ural Mountains area after he and his mother, Fanya, were sent there by the Soviets from Kiev.

The two groups of Privens compared notes and confirmed that they are second cousins: Rudolf’s grandfather, Haskel Priven, was a brother of Morris Priven, the grandfather of Lew and Cheryl. Morris had left Pavoloch for the United States in 1922 and settled in Boston, where he worked as a carpenter. Julius Priven, a son of Morris and the father of Lew and Cheryl, spent his working life in kosher meat markets.

Lew and Cheryl had diagrammed a detailed family tree based on conversations with their father. The tree proved invaluable in establishing the connection to Rudolf Priven’s side of the family.

Rudolf Priven “remembered enough and had the names of these people in his phone book, so we knew they were the same people,” Lew Priven said.

Learning that she has American kin is “quite amazing,” Anna Orchard, the daughter of Rudolf and Natalya and herself a physician, said from Salt Lake City, where she still lives.

Like her American cousins, Orchard had long assumed that her Priven branch was the only one still around. And, like them, her assumption was happily proved wrong.

(To search the Yad Vashem database of Holocaust victims’ names or document the names of relatives who were killed, go to www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/remembrance/names/index.asp. Please email Hillel Kuttler if you would like “Seeking Kin” to write about your search for long-lost relatives and friends; include the principal facts and your contact information in a brief email. “Seeking Kin” is sponsored by Bryna Shuchat and Joshua Landes and family in loving memory of their mother and grandmother, Miriam Shuchat, a lifelong uniter of the Jewish people.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.