Bronislaw Huberman, played by Thomas Kornmann, holding auditions for the Palestine Symphony in a reenactment scene in “Orchestra of Exiles.” (Irina Tubbecke)

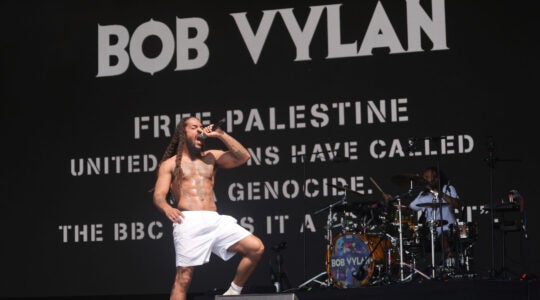

Arturo Toscanini, left, and Bronislaw Huberman on stage after the first Palestine Symphony concert in 1936, as seen in “Orchestra of the Exiles,” a film by Josh Aronson. (Courtesy of the Felicja Music Center Library/Huberman Archive)

(JTA) — This is the Holocaust story you don’t know. Almost guaranteed.

Bronislaw Huberman, a Polish-Jewish violin prodigy from the late 19th into the 20th century, is the protagonist, joined by familiar names such as Albert Einstein and the acclaimed (non-Jewish) conductor Arturo Toscanini. It is the tale of the founding in 1936 of what would become the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra and how Huberman, its founder, saved more than 1,000 Jews in the process.

“Orchestra of Exiles,” a new documentary produced, written and directed by Oscar-nominated filmmaker Josh Aronson, tells the saga, which is almost unknown outside of Israel.

No book in English chronicles the story, which Aronson assembled primarily from the violinist’s archives in Tel Aviv.

Even Aronson, a concert pianist himself and married to a professional violinist, had never heard of Huberman when he was approached by a musician friend who said she had a terrific idea for a movie.

“As a documentary filmmaker who has made more than one film, this happens often. Usually, it’s someone telling you about a family drama, or a dull little story … You are always very polite,” Aronson said in an August interview with WAMC Northeast Public Radio.

“Bronislaw WHO? I have no idea what you are talking about,” Aronson recalls telling the friend, Dorit Grunschlag Straus, when she broached the topic of a documentary about Huberman’s pre-World War II heroics.

Yet because of Huberman, Straus’ father, the Viennese violinist David Grunschlag, survived the Holocaust along with his parents and two sisters, when Huberman guaranteed him passage out of Europe to play in a world-class orchestra of exiles he was assembling in Palestine.

“In a cultural aha moment that would change the course of history, Huberman saw the opportunity to both save Jews and to found the orchestra that would become the great Israel Philharmonic,” Aronson said.

Huberman, who had launched his European career at the age of 12 by playing the Brahms Violin Concerto before the composer himself, had played before heads of government, kings, princes — in those days, says Aronson, top society lionized classical musicians. Through this privileged access he learned of the threat that Hitler’s rise posed to Germany, as well as the reticence of other nations to intervene diplomatically.

Influenced by his own brushes with Polish anti-Semitism in the 1880s and the Zionistic inklings of Einstein, a fellow violinist who later helped him raise funds for the orchestra, Huberman acted when musicians were fired in Germany after Hitler came to power in 1933.

Canceling all of his engagements in Germany — he never returned — Huberman dedicated himself to convincing the most accomplished Jewish musicians in Europe to relocate to create an orchestra in the Tel Aviv desert.

“One has to build a fist against anti-Semitism,” Huberman says in the film. “A first-class orchestra would be that fist.”

From 1934 to 1936, he auditioned, he accepted, he turned down musicians. In his homeland of Poland, Huberman conducted blind tryouts to assure himself that his choices would be based solely on musicianship.

“It would be a misnomer, though,” cautions Aronson, “to say he was in a godlike position.“ One can’t look at history in hindsight, he says; no one, including Huberman, foresaw concentration camps, and Jews were used to the vicissitudes of anti-Semitism.

Toscanini entered the story after he refused to honor a gig in Germany that he had accepted before Hitler’s ascension. When Huberman learned of the maestro’s principled resistance to fascism, he immediately asked him to conduct the opening concerts in Palestine, which he did.

The de facto leader of the Jewish community in 1930s Palestine, David Ben-Gurion, also played a supporting role — actually, non-supporting — in the drama.

In 1936, Huberman balked at bringing over the 70 musicians and their families because Ben-Gurion would only extend temporary entry documents to them rather than the precious permanent ones desperately needed. Ben-Gurion believed that only workers would build Israel, not urbane performers who would get off the boat, take one look at the camels and sand, and make a beeline back.

World Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann intervened and the Palestine Symphony held its first concerts in December 1936.

For Aronson, who calls himself a classic twice-a-year Jew, the project offered the opportunity to immerse himself in Holocaust history, something he had never done. It’s not that he grew up in a family that was unaware. His father, Aronson says, would never set foot in Germany and didn’t like the fact that his son owned a Volkswagen.

But for the year he researched Huberman and the Israel Philharmonic, Aronson read books he had never read, explored Yad Vashem and the Holocaust museum in Washington.

“I gave myself the education on this painful topic that I was too intimidated to go after years ago,” Aronson said.

Aronson says that in producing the documentary, he was fortunate to meet the aristocracy of Israel — the octogenarians who saw Zionism at its beginnings — as well as musicians who create music today at the highest levels. Among those interviewed for the film were artists such as Itzhak Perlman, Joshua Bell, Pinchas Zukerman and Zubin Mehta. (I won’t spoil a final anecdote: Good story embedded in the movie about Bell, whose violin teacher worshiped Huberman.)

In the end, how many Jews did Huberman save? Aronson suggests about 1,000, but notes that some Israelis claim it was closer to 3,000 after tallying players, parents, wives and others swept along.

There are no records, he says, since Huberman didn’t need or want accolades.

“He was doing this because he saw intolerance and, unlike so many who did nothing, felt compelled to act,” Aronson said. “Maybe because he had such a big heart.”

“Orchestra of Exiles” opens at New York City’s Quad Cinema on Oct. 26 and in Beverly Hills and Encino, Calif., on Nov. 2.

(Elisa Spungen Bildner is the co-chair of JTA’s board of directors.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.